“There’s a fallacy perpetuated by some that government is fat and wasteful,” says Eric DeLong, deputy city manager for the City of Grand Rapids, MI. “We’ve had to cut almost 300 people, and we’ve still found a way to provide exceptional services in most cases. I challenge people to come here and find any fat.”

With a history of innovation dating back to 1916, when it was one the first municipalities to enact a commission- manager form of government, the City of Grand Rapids, MI, has embarked on a lean journey that has freed up limited resources and improved customer service.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t any opportunities for the city to do more, and do it more efficiently. Inspired by local businesses and coaxed by the mayor and city manager, DeLong has led a team on a lean thinking initiative that will eventually touch every administrative department of this city of 200,000 people. After two and-a-half years, they’ve done more in some areas than others. But the important thing is that they continue to make progress.

Like many lean transformations in the private sector, external forces had a hand in pushing city leaders to find a better way of doing things. With its economy tightly linked to the fortunes of U.S. manufacturing and the auto industry, in 2006 Michigan was the only state in the country where GDP declined from the previous year, according to figures from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Adjusted for inflation, Michigan’s GDP fell 0.9 percent from 2003 to 2006. Over this same three-year period total employment climbed just 1.0 percent. The unemployment rate for December 2007 was 7.6 percent compared to the national average of 5.0 percent.

In Grand Rapids and other Michigan cities, flat tax revenues and rising healthcare costs have contributed to perennial budget shortfalls. Compounding the problem, Michigan’s state government has been struggling with billion-dollar budget deficits of its own. It has frozen and cut millions of dollars of revenue-sharing payments from sales taxes that it used to give back to municipalities. To balance its budget and make up for $9 million in annual funding no longer provided by the state, Grand Rapids has eliminated hundreds of jobs over the past six years. Today, the city employs around 1,700 people. While the city’s lean initiative hasn’t made up for the job losses, it has helped to temper the impact.

“The essence of lean thinking is to engage staff members responsible for the work in redesigning it, keeping in mind the need to provide the best possible product or service to our customers,” DeLong wrote last May in a progress update to the mayor and City Commission. “Lean thinking is also a critical way of coping with the reduction of 282 employees which has taken place over the last six years.”

One of the challenges of the city’s lean initiative has been convincing people internally and at the City Commission level that it’s not about figuring out new ways to cut more city personnel. By applying lean principles and tools to their departments, many city employees have learned firsthand how consolidating operations, eliminating wasted time and effort, and streamlining processes can help them provide the quality of service that city residents want, in less time and with less effort and frustration.

“I think we’ve overcome the misconception that it’s about eliminating people,” DeLong says. They’ve also overcome some of the baggage from previous change initiatives that had varying degrees of success. “If you’re an adventuresome organization, you have probably tried a lot of things because you’re always working to get better,” he adds. “It’s important to prove to the organization that this is how we intend to do business.”

City of Grand Rapids, MI, at a Glance

- Location: West central Michigan, 30 miles east of Lake Michigan, on the Grand River

- Population: 197,800 (2000 U.S. Census)

- Area: 45 sq. mi.

- Government: Six elected commissioners from three wards plus the mayor, who is elected at large, and the city manager (appointed)

Starting at the Top

Before it could get off the ground, Grand Rapids’ lean thinking initiative first had to get approval from the City Commission. Voters here elect two commissioners from each of the city’s three wards. Elected at-large by the entire city to a four-year term, the mayor is the official head of the city and presides over council meetings, but he has no veto power over the commission’s decisions. The commission hires the city manager who serves as the chief administrator. The city manager is responsible for the coordination of all departments and for the execution of policies set by the commission.

As the local economy continued to struggle, lean success stories at manufacturers and other businesses in the region, including a local hospital, caught the ears of both Mayor George Heartwell and City Manager Kurt Kimball. After further research, and conversations with various advisors, they became convinced that applying lean principles could help the city maintain customer service levels with fewer resources. In making their lean proposal to the commission, they promised results, just like a chief operating officer would promise results to a board of directors. They received support from a majority, but not all, of the commissioners.

To be successful in the long run, any lean program has to have executive-level commitment. In Grand Rapids, Mayor Heartwell talks about the city’s lean thinking program when he’s out giving speeches. City Manager Kimball writes about it when he’s putting together the annual budget. They do all of the things that the leaders of any organization must do to signal that something is important.

“Because we are a public organization, we have to be very deliberate about how we implement things or it doesn’t work,” says Kimball. The fact that they’re still talking about it after several years clearly demonstrates that their lean thinking initiative is important and isn’t going away.

Setting Priorities

A lean team led by Deputy City Manager DeLong and made up of department heads and other senior management coordinates the city’s lean efforts. This team identifies the value streams where they need to focus attention. A value stream includes all of the actions, both value-creating and non value-creating — almost always crossing departmental boundaries — that it takes to deliver city services to customers. The team also keeps tabs on current projects. When the program launched in 2005, the team visited Monarch Hydraulics, Inc., and Saint Mary’s Health Care, a local business and not-for- profit that have had some success with their lean initiatives. The visits helped the team members to better understand the opportunities within their own departments.

To provide training, and to lead the first value stream improvement workshops, DeLong brought in Tom Shuker, a Lean Enterprise Institute faculty member and president of Lean Concepts LLC. Shuker is a 30-year veteran of GM. Among other manufacturing roles, he spent two years at New United Motors Manufacturing Inc. (NUMMI), the GM-Toyota joint venture in Fremont, CA. He has co-authored several books and workbooks on value-stream management and how to apply lean concepts to administrative areas.

DeLong says that retaining a consultant who could provide the fundamental lean training and facilitate their initial workshops was critical to their success. In searching for such assistance, he advises, you have to find someone who can talk about lean just as easily with top managers as they can with everyone who participates in the lean projects.

From the beginning the city’s goal has been to develop internal competencies so they wouldn’t be reliant on outside assistance. To that end, Shuker provided in-depth lean training to a select group of staff members, some of whom then helped to facilitate the initial value-stream improvement workshops. They now facilitate the city’s workshops in teams of two without the need for consultant assistance. Each of these workshops consists of an initial scoping session followed by a three-day event. During these all-day sessions, participants map out the current process to see what’s working and what activities can be eliminated or adjusted, they sketch out a future-state process, and then develop an implementation plan. Today, the city only asks Shuker to come in and help out when they’re tackling a particularly difficult value stream.

Defining the Value Stream

The root cause of the rare workshop failures that Grand Rapids has experienced can be traced to the initial scoping phase. After the lean team has selected the process that needs to be improved, and identified the process owner, they schedule a three to four hour scoping session that includes those employees most closely associated with the targeted areas. During the scoping session, the group agrees on start and end points for the value stream and reviews performance metrics and objectives. With resources stretched thin, it can be a struggle to pull people away from their regular jobs for three days.

“I really appreciate the fact that people are willing to work earnestly on these value streams because they are doing it in addition to everything else,” says DeLong.

The scoping session also determines who will be on the “decision panel.” The decision panel reviews the workshop participants’ future-state proposal after the second day, and provides the resources needed to execute the implementation plan that the team develops on day three. The panel is usually made up of a mixture of lean team members, department directors, and may include Delong, the city manager and even members of the City Commission.

Grand Rapids’ initial workshops targeted three areas: the material return process at the Public Library, the purchasing process, and the engineering design process. Touching almost everyone who works for the city, the purchasing department was selected because any improvements would have a broad impact. The department happened to be undergoing management changes, which made it a good time to redesign the process. The Engineering Department was also in a state of flux. Its budget had been moved out of the city’s General Fund. As a separate business unit, the department now works more like an independent engineering firm, relying on earned billings for survival.

“In retrospect, the Public Library was a brilliant choice because it was the right-sized value stream. The scope was appropriate. We’ve tried to follow a 30-, 60-, 90-day implementation plan. And the library met that target,” says DeLong.

After almost two years they’re still implementing the recommendations that came out of the initial purchasing workshop. Partly that’s because of some personnel changes and the time required to implement a complex IT solution. What they have implemented so far has worked. First-time quality was zero when they started. Today, the percentage of requisitions that go through the process without any rework is way up. The Engineering Department is still implementing changes as well, for different reasons.

“What could have been broken down into multiple value stream workshops [for Engineering] ended up being one. We got a great solution but it has taken time to move it through the system,” says DeLong. Since these three initial workshops, the lean team’s scoping has become more concise, and results are coming more rapidly.

The Magic of the Current-State Map

Following the scoping activity, the first day of a value-stream improvement workshop starts with a lean orientation. The facilitator explains how the workshop is supposed to work and introduces lean principles, including value-added and nonvalue-added work, focusing on the needs of internal and external customers, continuous improvement and key metrics. Following the general guidelines that have recently been documented in Mapping to See training kit (Lean Enterprise Institute, 2007), this introduction is followed by a value-stream mapping exercise.

“Then we start the magic of drawing the current-state map,” says DeLong. “We know the beginning point and the end point from the scoping session. What happens in between?

It’s amazing what comes out of that.”

The mapping exercise helps participants visualize everything that everyone does, see the delays, ask questions, and begin to think about solutions. This step can generate a lot of emotion and angst. If there’s blame, if there’s conflict or anger, it always pops up on the first day. At times, the facilitator has to be part psychologist and part referee to help people get through their feelings of loss, anger, and frustration as their work and job are scrutinized.

“If anyone comes into the workshop thinking that everything is perfect, by the end of the first day they know it’s not,” says DeLong. “Sometimes you see these hurricanes of rework, it’s usually between a couple steps in the process, and it becomes pretty evident what needs to be fixed.”

Two years ago, the city’s Fire Department tackled its business inspection process. The value-stream improvement team included the fire prevention inspectors, an IT manager, and a representative from the building department, which passes new construction over to the Fire Department when it’s time for the owner to get use and occupancy permits.

“Because it was so obvious that we had a problem with the whole process, it was much easier for everybody to get involved and make a change,” recalls Laura Knapp, deputy fire chief for Grand Rapids, who is the process owner for this value stream. “Initially, when we started laying it out on the board, sure there were some outside things that people wanted to bring in, and blame problems on workload issues. Getting them focused on just this process was a little bit difficult.” But once they were focused, they were able to map out the current work flow and move on to the next step.

On the second day of the value-stream improvement workshop, the teams start by considering what the customer actually needs and when it’s needed. Looking at the current-state map, they identify opportunities to smooth the work flow. They look for rework, unnecessary duplication, steps that can be combined or eliminated, and areas where the workload needs to be better balanced among staff members. The team pays close attention to the flow of information, which can be a big contributor to delays and rework.

For example, when the customer is internal they can contribute to delays by not providing the correct information when it’s needed, as was the case with the city’s requisition process. In many cases the necessary information wasn’t being forwarded to Purchasing so it could produce a Purchase Order. This basic realization has changed the attitudes of some people who used to blame other departments for their mistakes, according to DeLong. The cross-functional structure of the workshop helps overcome misplaced blame, opens up dialog between departments and begins to break down departmental silos. At the end of the day the team emerges with a future-state map and a much-improved workflow that everyone can start to visualize. They then present that future- state map to the decision panel.

“They know they’re going to show it to a senior management team, so there’s an edge to doing a good job,” says DeLong. “They’re always very interesting presentations because you can see that they have really internalized the work already, they’re committed, and they really want to improve it.”

That’s very different from the response managers usually encounter when they start talking about “change.” The difference with lean is that the people doing the work have identified the problems and potential solutions. The presentations to the decision panel prompt senior management’s buy in to the solution, getting them to commit resources if necessary and to provide protection from other priorities. Almost all of these sessions have gone well.

“The process depends on the decision panel not just being a rubber stamp,” says DeLong. “If they haven’t delivered, you have to tell them.”

That happened with one value-stream improvement workshop that focused on the handoff between the Development Center, which facilitates development and approves developers’ plans, and the Building Department, which inspects new construction. The team developed a future-state map in which all of the proposed workflow changes were within one department, and the actual handoff hadn’t been addressed. They had designed a new process that would have guaranteed that no development projects would be approved the first time through. The decision panel asked them to go back and try again.

The second time through Tom Shuker helped facilitate the development of the future- state map. Shuker reports that more dialog up front with people in both areas, and consistently communicated objectives, would probably have avoided the initial misfire.

Day Three: The Implementation Plan

Now that the team knows where they’re headed, workshop participants meet again on the third day to develop an implementation plan. The team establishes detailed 30-, 60- and 90-day goals, and assigns responsibility for meeting the milestones. At the end of the day the decision panel reviews these plans as well. Despite the participants’ best efforts and cross-functional involvement, during execution process owners have sometimes run into unexpected complexities, which have delayed implementation.

“The important thing for us, we determined, is to make it happen at all,” says DeLong. “If we can get it done in 90 days, that’s great. If it takes 180 days, that’s okay too, because in the end you have an improved process.”

For Good Measures

Performance measurement in a manufacturing plant where everyone is trained to keep a close eye on part costs, cycle times, and quality, is relatively easy compared to an administrative setting where the work is much less visible. Pressured to report a return on their investment in lean — specifically the cost of bringing in an outside consultant and hundreds of hours of employee time — the Grand Rapids’ Lean Team developed some core metrics.

In addition to overall lead time (the total time to provide a service from initial engagement through delivery), the city’s value-stream improvement teams track process time (the amount of work done to complete a task), wait time, and productivity. Any wait time reductions that they can achieve between their current and future- state maps translate into better customer service. While such benefits can’t easily be monetized in a government setting, serving customers better is always good, and it has the added bonus of making people feel better about their work.

Reductions in process times are another story. Process changes that reduce work requirements reduce hourly labor costs. Even if that labor is dedicated to other critical activities, these savings can be calculated. For example, by reducing the amount of time required to execute a building inspection from 10.3 hours to 4.5 hours, mostly by increasing first- time compliance, the Fire Department saved 5.8 hours per case and more than doubled productivity. Averaging 500 inspections per year, this equates to 2,900 hours. A savings of 2,900 hours at an employee hourly rate of $40/hour works out to $116,000.

Other savings from this project that could be calculated include a reduction in fuel and depreciation for city vehicles because of fewer trips that inspectors have to make to a single building. In the long term, even though they’re already at a fairly low frequency rate, increasing the number of code compliant and safe buildings saves money by reducing the number of fires.

“It’s not an exact science, but it is important to do the best you can do to demonstrate results,” says Eric DeLong, deputy city manager.

The Fire Department’s inspection team was able to meet the 90-day implementation target. They used a project monitoring model that the city is adopting for all value- stream improvement projects. It’s a simple spreadsheet with action steps, responsibilities, and review status indicators; red indicates that an item hasn’t been started, yellow that it’s in process, and green that it has been completed.

“You have to realize that it’s a commitment and you have to stick to that commitment,” says Deputy Fire Chief Knapp. “You need to stick to the timelines as close as you can and see it through. When you let things continue out and go on and on, other priorities come in.”

With the overall goal of increasing the number of fire code-compliant buildings, and reducing the number of fires annually, the fire inspection team developed a pre- inspection checklist and a new inspection form. By educating their customers about fire code requirements, they gave business owners an opportunity to identify and correct violations before inspectors arrive. As a further incentive, they now waive inspection fees if a facility is compliant on the first inspection, and even extend the time between scheduled inspections depending upon the type of facility. Such efforts have increased the percentage of first-time compliant businesses, dramatically reducing the need for re- inspections.

“The key to code compliance is education,” says Knapp. “There are always going to be some business owners that aren’t going to buy into some things. We have to deal with those individuals. But you can show them the value in maintaining their business and talk about safety for their customers, employees, and firefighters.”

The Fire Department has also streamlined the inspection intake process, improved electronic access to case information, and eliminated some unnecessary steps.

Inspectors used to do an inspection and then come back to the office to type it up and mail the first violation letter requiring correction within 30 days. Now, they issue the first violation notice on site at the end of the inspection, cutting days out of the overall lead time.

Such changes have reduced processing time per case from 10.3 hours to 4.5 hours on average, doubling the number of inspections that they can complete in a year.

The changes to the inspection process have supported an IT project that will give inspectors full mobile access to case information when they’re out in the field. Knapp believes that fixing the inspection process first has helped them to avoid automating steps that did not add value.

“For me, the whole lean thing just makes a lot of sense. It’s something that I think a lot of people do all of the time, but they don’t do it in a formal way,” Knapp adds. “You look at one piece of the whole process and see what you could do differently, but you never sit down and look at the whole thing.”

Don’t Defeat Spontaneity

Even though their departments were not selected for the pilot projects, some members of the lean team were so inspired by the initial two-day training program that they started projects on their own. “All of the sudden we had three value-stream processes happening that weren’t supervised, that were lead by champions who had a modicum of training and facilitators who had even less training,” DeLong recalls. After some initial reservations over these “renegade” projects, he decided to step back and see what happened.

The Community Development Department pulled together people from their Housing Rehabilitation and Accounting divisions to map its process for granting homeowner rehabilitation loans. They discovered that the loan approval and closing process had a wait time of 20 weeks. Internal processing time was over 28 hours. Incomplete applications contributed to significant rework. The team’s initial improvement plan reduced homeowner wait time to 12.5 weeks and internal processing time to 21 hours.

Following some personnel changes, they’ve since attacked the loan approval process twice more to formalize the process improvements and maintain performance levels. As DeLong reports, “They found out that if you don’t write down the rules, and aren’t very specific, then the next person who comes in, they’re going to do it their own way.”

Another renegade project addressed the city’s parking card refund process. Mapping it out, the Parking Services staff found that it took customers 20 days on average to receive a refund check, and 32 minutes for them to process and approve the request. Because it was thought to be more efficient, the majority of the delay came from holding requests until there was a large enough batch to enter them into the accounting system.

Of the 440 annual parking card refunds, 85% were for less than $50, and 60% were for less than $25. When they sat down to figure out the future state, the team realized that they could process the vast majority of refunds at the counter if they had $500 in petty cash on hand. With permission and assistance from the city’s Comptroller’s Office, they were able to reduce customer wait time from 20 days to 12 minutes, and processing time to 14 minutes.

Why couldn’t the Parking Department implement such improvements independently of the city’s lean thinking initiative? Focusing directly on the needs of the customer and involving the frontline staff in identifying problems and solutions is not standard management practice. The lean methodology that Grand Rapids has adopted is bottom up, allowing employees and managers to generate and organize ideas that wouldn’t happen otherwise.

“We’ve usually tried to think our way to a new way of acting,” says DeLong, recalling past transformation efforts “Thinking to a new way of acting has some value, but the way lean works is the reverse of that. If you’re doing it, you internalize it, and all of the sudden you’re thinking differently.”

Other processes that the city has addressed or begun to address through lean workshops include contract compliance in the Equal Opportunity Department, how they issue water tap permits, how cash receipts from satellite departments are transferred to the Treasurer’s Office, and collections at the District Court. They’ve had to balance these initiatives with budget cuts and leadership transitions, struggling at times to maintain momentum.

Sustaining their progress, DeLong has discovered, requires a good communication network. Last summer he realized that the lean team was losing track of the status of the lean initiatives in each department. They have since worked to standardize the reporting procedures for the process owners.

“It’s like any other campaign, you need to set up your communication tools,” he says. In addition, team members are now assigned as a coach to each process owner. In part, they are there to keep him informed. Still, keeping it all going requires a never-ending effort and commitment.

“It’s not just finding a lean consultant, although that’s critically important,” says DeLong. “It’s not just having the resources to pay the consultant, although that’s important. It’s not just having a lean team or doing the value streams. It’s about having a vision for where this is headed and finding the time to stick with it that’s critically important. It has to become a business practice. It has to be as natural as taking a shower and brushing your teeth.”

Lean Principles Heal Poor Circulation at Public Library

Local patrons may know little about the lean thinking initiatives that have been happening behind the scenes at the Grand Rapids, MI, Public Library, but they have certainly enjoyed the benefits. Today, high-demand materials, both new items and those already in circulation, are available days and even weeks faster than they were only a couple of years ago.

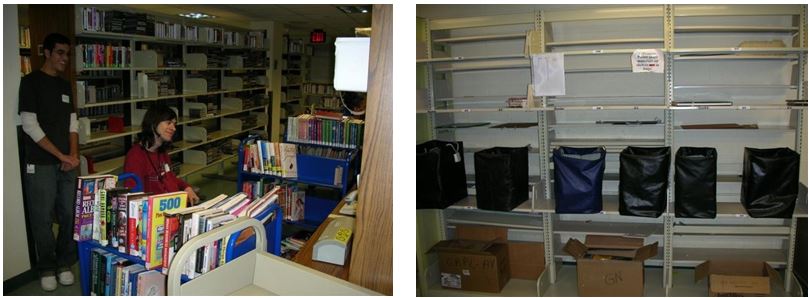

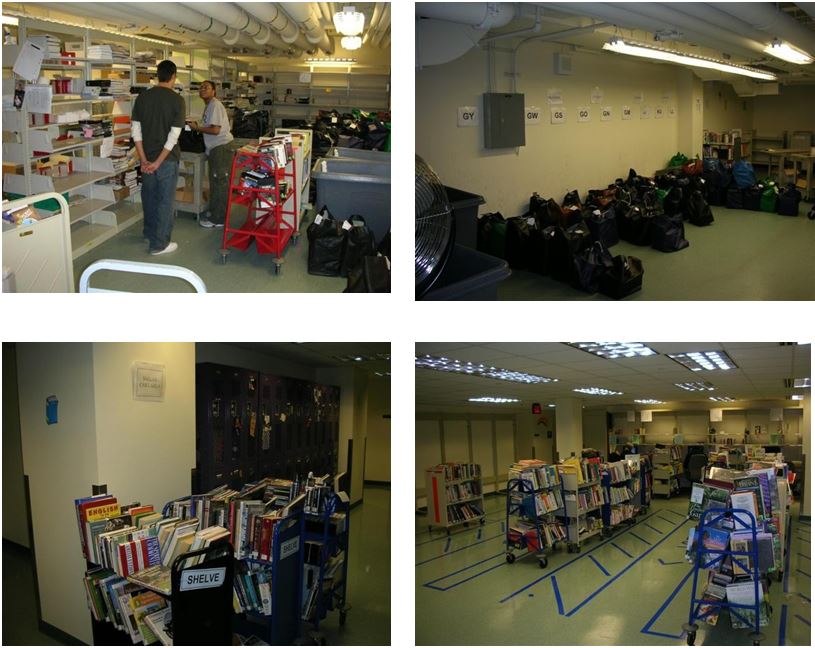

The library system consists of a main downtown facility and seven branches located throughout the city. Every year it serves over 1 million visitors and circulates over 1.5 million items. Two years ago it was selected for one of the city’s initial lean projects. Library managers targeted the material return value stream. The goal: Get all materials returned by patrons or from branch libraries back on the shelves within 36 hours. Because they are circulating, these books, CDs and DVDs, tend to be the most popular.

The library formed a team comprised of the circulation managers, other library personnel, city representatives and pages (the part-time employees responsible for receiving, sorting and shelving returned books). The team started by walking the process from the moment materials arrived to when they were available to patrons. They then mapped it out on a large piece of laminated paper. The team discovered that each item was being handled nine to 12 times, with significant delays at each step. They also found blocked bins, material in the wrong location, the absence of a priority system for new items, and multiple locations for the same materials.

After analyzing the areas with excessive wait times and looking for steps that could be consolidated, the team developed a future-state map that dramatically streamlined the material flow. Having designed a process that would reduce touches to six times and average lead time from 126.5 hours to 3.5 hours, team members presented their proposal and implementation plan to a decision panel made up of city and Library managers for approval.

The redesigned process utilizes core lean principles and techniques to eliminate unnecessary material movement and speed material flow. It has helped the Library’s Circulation Department manage an 8% increase in circulation volume since 2004 with the same number of page hours and just one, instead of two, supervisors. Specific changes included:

- The development and documentation of standard receiving, delivery and shelving processes.

- Elimination of all shelving in favor of wheeled carts pre-labeled by destination.

- A standard check-in process that incorporates an initial sort by material type, eliminating a step that used to be performed in the Circulation Department.

- Creation of a first-in, first-out (FIFO) material flow.

- Assigning a dedicated person to material conveyance (a “water spider”) to keep carts moving between intake points, the Circulation Department and each floor.

- Development of a balanced and level workflow written out on a dry-erase board that matches workforce hours to available work.

- Constant cross training so that pages can go where they are needed to keep materials flowing.

- Establishment of cart holding locations on each floor, instead of waiting in the basement, where patrons can browse through recently returned items before they are re-shelved.

Part of the city’s lean strategy, according to Eric DeLong, deputy city manager, is to transform an area that everyone recognizes as a problem area, and have that success set an example for other value streams. And set an example the Library project did.

In the Library’s technical services department a value-stream improvement workshop guided the rearrangement of the office layout to speed workflow. The net result: the percentage of new materials that they catalog and put into circulation within 10 days has increased from 18% to 96%.

Elsewhere, the Business Office conducted a lean workshop that helped them reduce the time required to prepare payroll each month. Mostly by moving from hand-written timesheets to an electronic data entry and approval process they cut lead time from 7.5 days down to 3 days. And within the Acquisitions Department, a lean project reduced the number of separate orders for popular fiction titles over a four-month period from 547 down to 90.

Beyond such measurable results, lean thinking has become part of the Library’s culture, according to spokesperson Kristen Krueger-Corrado. People no longer view the current processes as being written in stone. She adds, “Now, when we’re talking about doing things, we’ll say, “That’s not the lean way to do it.’”

| Attribute/metric | Current-State Performance | Future-State Goal | Actual Result (12/27/2006) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process time (seconds/item) | 180 seconds average | 39-122 seconds (shelf), 56 seconds(holds) | 29 seconds per item |

| Lead time | 14-267 hours (126.5 hours average) | 5-12 hours (3.5 hours average) | 5-36 hours (longest time: 36 hours) |

| First time quality | 93% | 99% | 95-99% |

| Number of times material is picked up and set down | 9-12 times | 6-7 times | 6 times |

Grand Rapids Public Library Returned Materials Value Stream Workshop Results

| Before | After |

| Receiving |

| Before Prep, Check In and Sort | After |

Intro to Lean Thinking & Practice

An introduction to the essential concepts of lean thinking and practice.