Part eight of eight. Watch the others.

- Part one, A Focus on Muda

- Part two, Overproduction

- Part three, Excess Inventory

- Part four, Excess Conveyance

- Part five, Motion

- Part six, Waiting

- Part seven, Defects

Hi everyone. I’m Art Smalley, president of Art of Lean, Inc. Today, on behalf of the Lean Enterprise Institute, we’re going to do a series of short video clips, each one about the seven classic forms of waste from the Toyota Production System. Stick around. I think you’ll enjoy them.

Waste No. 7–at least for me, I put it seventh because it’s a bit of an oddball or odd duckling, and I’ll explain in my intellectual criticism of the seven ways framework why I think that is in a follow-up video. It’s the waste of processing or the waste of over-processing. There are two ways you got to look about it.

Are You Over-processing?

One is the simple over-processing, of doing something beyond special requirements beyond customer requirements, beyond the required level of value-add. That can be, you know, over quality, over-specification, overprocessing in some way, shape, or form.

Here’s a simple example. My friends in the Navy might appreciate this. I’ve got this steel ball here, and I’m going to put it through this machine and make the nut we were doing before. But before I do that, let’s say I polish the steel ball. I polish the steel ball and get it clean. Then I put it in the machine, cycle it, operate it, and make my part. And the question is, do you need to clean it before you put it through the machine?

I guess, in the Navy, they call this polishing the cannonball. That’s a form of waste because if you’re going to shoot it through the cannon, what’s the point in polishing it in the first place? I guess that’s an old Naval adage–or something like that–that got shared with me once. And it’s a legitimate form of over-processing because going through the machine, it doesn’t need to be clean, potentially. You know, maybe you do need to clean it in some cases in order to not have a jam or make the right quality component come out. But in other cases, maybe you don’t need to clean it before it goes through the machine.

It’s a legitimate question. What level of cleanliness, what level of processing needs to be there? And that ties back to a great understanding of customer standards and requirements–what’s really required–and not going beyond them when you don’t need to. Because going beyond them adds time, adds difficulty, adds processing, adds costs in some way, shape, or fashion. You need to look at that very carefully.

Are You Using the Right Process?

Another way of looking at processing is not just over-processing, and this gets lost in the translation, unfortunately. In the original Japanese, it wasn’t overprocessing; it was emphasized that it’s also is the act of processing itself. Is the act of processing itself the correct way or best way? Here’s a household example I can use to make in the video.

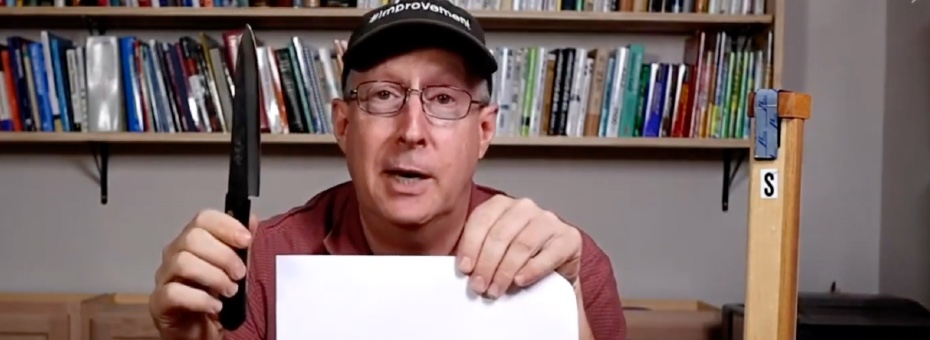

I’ve got a piece of paper and my wife’s steak knife–and hopefully, she never sees this, but I can actually cut paper using the steak knife. And it cuts through it pretty sharp because I like sharpening knives–it’s a hobby of mine, so I have a lot of sharp knives in my house. But that’s not really the best way to cut. It did make a straight cut in this way, but I can’t control it. I can’t go on straight lines and do fancier things with it. If you want to cut paper, of course, the proper tool way of processing it, you know, even freehand, I make a better cut with scissors, and you can go up gradually from this to, you know, the lever types and slicing types and more advanced types of ways to cut paper. Okay. Go crazy with lasers and cutting action and things like that.

But the act of processing itself, you have to look at some time and ask, is this the best way, is this the most efficient, effective way to do it at our cost structure? Often, it depends. How do you want to process something is a fundamental question you have to think about during the product development and production engineering stage.

If you don’t, sometimes it gets into production–you wind up processing it in a way that’s inefficient and causes a lot of cost, a lot of waste, even if it’s not over-processing, just the style of processing you chose to do is not the most efficient.

So, again, this is seventh, but sometimes it’s a huge form of waste that needs to be looked at carefully over time, with a careful understanding of what customer requirements are. That is the seventh form of waste.

The Value of Focusing on Waste

That concludes our videos on the seven classical types of waste that were in the Toyota Production System from the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and onward until this time. Of course, your organization might have changed the names slightly. You probably order them differently or have an acronym associated with them for easier thinking. I presented them in the fashion that I thought about them and how I probably learned them at a Toyota factory where I worked in Japan.

But there’s no perfect way to explain them, and there are some intellectual shortcomings, to be frank, in the framework. I’m going to save that for a follow-up video—and, no, I don’t mean I have to add the eighth waste, and that saves everything. It just introduces another layer of problems.

But, as a starting point, the seven wastes are a good way to challenge people to think about their motion, their daily job, and the work they perform. Is that work value-add, is it incidental and required in the current state of the process? Or are there things truly wasteful and unnecessary that we do?

Again, the spirit of this was, in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, in Toyota was to catch up to the West. And improve their levels of labor and capital, productivity, and overall company profitability by subtraction.

The elimination of waste, which comes back to that JM [Training Within Industry Job Methods] framework: eliminate the unnecessary details—Eliminate, Combine, Rearrange, and Simplify—and make things better. If you can engage people mentally in their job with problem-solving, continuous improvement, and the actions they perform, I think it makes for a better, healthier workplace and management relationship set of structures for all of us.

I hope that helped, and good luck with your improvement journey.

Intro to Problem-Solving

Learn a proven, systematic approach to resolving business and work process problems.