It is okay in the world of writing, it seems, to borrow or steal titles. If you cite the original, you are borrowing. Don’t and you are stealing.

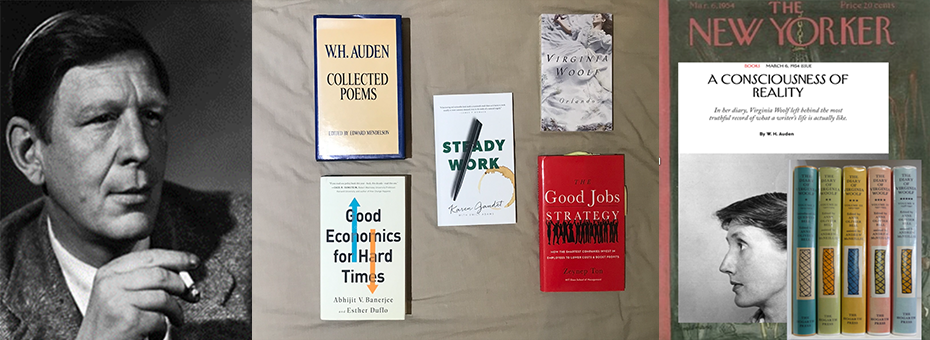

I borrow the title above from WH Auden’s short essay (New Yorker 1954) about Virginia Woolf. Quoting WH on Virginia:

“What is unique about her work is the combination of this mystical vision with the sharpest possible sense for the concrete, even in its humblest form: “One can’t,” she observes, “write directly about the soul. Looked at, it vanishes; but look at the ceiling, at Grizzle, at the cheaper beasts in the Zoo… and the soul slips in.”

What does such literary height have to do with the pedestrian stuff – lean thinking & practice – that we write about in this space? At some risk of sounding pretentious – everything.

Mountains of words, worlds of words even, have been compiled in attempts to define or explain what we call “lean thinking”. None of them do it justice. That fact doesn’t bother me much. But it bothers others. And that fact bothers me a bit. Individuals and organizations expending human effort, sweat, toil, capital, dollars in sincere (sometimes) efforts to make things better, yet feeling frustration when things don’t go according to plan. When we humans try to gather ourselves together to accomplish something, what often ensues is everything BUT that something we set out to do. But, in the process, great things also come about. Sometimes anticipated, often not. Lean thinking & practice help us get better at getting better. That’s the gist of it.

Lean Restart

I’m comfortable with that. Comfortable with ambiguity, you could say. I am much less comfortable with unnecessary struggle. With seeing sincere effort end in frustration and endless re-starts. Lean Restart we could call it.

Much of the difficulty in the disambiguation (a nod here to Jon Miller) process of lean thinking lies in the dilemma that WH recognized in Virginia’s work. Try to tie lean thinking down with an engineering process description and you lose the essence. As Doc Hall has put it, you “kill the snake” (ask Doc). You end up with something lifeless. Like six sigma done poorly.

“Virginia Woolf meets the Toyota Production System, giving rise to a consciousness of reality that recognizes the need to yoke ambitious aspirations with concrete strategies/tactics/practices at the most granular level.”But, equally true, if you attempt to describe only the organizational culture ramifications of lean thinking, you lose the concreteness, the exact same concreteness that WH observes in Virginia’s best work. You end up with employee empowerment programs that build up hope only to let it down because everything (the above-mentioned “engineering processes”) is broken. Nothing works. Well-intentioned initiatives beget jaded spirits, sitting ducks for the next Lean Restart.

Lean thinking & practice engages people at the deepest levels of their human aspirations. Deepest and highest levels. Want to end poverty? Want to provide better work to more people? Great – let’s unleash the visionary inspiration that is lean thinking at its core.

But, leave out the granular, gritty specifics entailed in designing and executing the design of good work – how to better wash the dishes in a busy restaurant, for example – and you end up with nothing but empty platitudes and broken dishes. Omit effort to truly understand the cause & effect dynamics of poverty, and you end up shipping boatloads of computers to villages with no electricity or water, wasteful of the earnest effort and good intention, to be sure, but also of the good will of those we purport to support.

High and Low (Aim High, Work Hard)

Two programs at MIT (disclosure: I have no connection with MIT, beyond giving an occasional lecture and frequenting their awesome bookstore) come to mind: J-PAL and GJI.

The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) is a global research center working to reduce poverty by ensuring that policy is informed by scientific evidence. Anchored by a network of universities around the world, J-PAL uses a network of around 200 researchers globally to conduct randomized impact evaluations to answer questions about how to better fight poverty.

J-PAL’s founder/directors Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee received a 2019 Nobel prize for their groundbreaking work. What makes their work groundbreaking sounds simple enough: use science (RCTs) to verify what actually works (imagine that) in the real world. Shove aside ideological debates grounded mainly on passion (in the guise of compassion) in favor of facts and data. Remarkable.

In a conversation with Duflo during a visit with colleagues a couple of years ago, the laureate-in-process told us how they have learned to formulate and address research questions about, for example, how to increase the number of families utilizing health aids. Advocates tend to dig in their heels for their pet approach, with one side arguing, “We should give critical health aids to the population for free” while the other side counters, “No one will value or use anything that is free”. J-Pal researchers worked through the emotional advocation to learn that two simple principles will go a long way: 1) Make it easy for people to do the right thing, 2) provide an incentive (small) for them to do it TODAY. Making it free versus giving it away was a non-factor. J-Pal’s impact evaluations test and improve the effectiveness of social programs, informing policy-making with scientific evidence.

Another program to grow out of MIT that connects grand ideals with granular details is the Good Jobs Institute (GJI). Founded by professor Zeynep Ton, GJI aims to “make the job of the future a good job”. According to Ton, a good job is one that meets people’s basic needs and offers conditions for engagement and motivation. Only providing basic needs such as a living wage is not enough to create a motivated workforce, but failing to provide those needs leads to undue stress, poor productivity, and high turnover. The GJI promotes a framework for good jobs with nine factors that enable companies to meet the key needs of any workforce – the Good Jobs Strategy.

Like J-Pal and Virginia Woolf, GJI yokes the lofty with the gritty.

Hitting Close to Home (or From Sandy Hook to COVID-19)

And here’s a third story of initiative that links lofty aspiration with dusty reality: Steady Work, a new book by LEI’s own Karen Gaudet. This personal account of her time as manager of the Starbucks region of 100 stores, including the one in Newtown, Connecticut close to the Sandy Hook Elementary School in December 14, 2012. Karen shares how a set of lean work and management practices made steady work possible for Karen and her team every day and how those practices helped her and her team survive the worst day at work any of them would ever have. Karen describes the practices and structured experimentation which enabled teams and individuals to develop powerful, learnable problem-solving capabilities that local managers adapted each store’s operating system to its local situation, all the while ensuring local responsibility for ongoing improvement.

Karen’s book describes adoption of Lean Thinking & Practice as a fully empowering approach that was owned by each employee who was touched by it. It wasn’t a competitive strategy separate from daily operations tactics—it was an integrated strategy that fostered problem solving at every level of the company. This story reveals the work and impact at both the personal and the systems level.

It should come as no surprise to anyone reading this if similar stories emerge as healthcare organizations that have adopted lean practices come to grips with the COVID-19 crisis. Healthcare workers are facing days at work that are tougher than most of us can imagine. Their ability to keep hold of their passion to care for the sick while at the same time focusing all their attention on the nitty-gritty of making sure everyone washes their hands (you, too, physicians) and covers their coughs (although this particular coronavirus seems to spread less through the air and more through touch). It’s purposeful attention to detail that will make the difference.

A Hopeful Place

Does anyone know the holistic “answer” to our biggest human problems – not merely the technical answers (though I imagine someone will send me theirs now) nor just clarion calls of emotional appeal such as, “if we can put a man on the moon, we can end all pandemics!”? The truthful answer is – despite the myriad prescriptions and “roadmaps” being pushed by solution-sellers – a decided no. Can we identify gaps big and small and break the problems down into bite-sized addressable chunks? Yes, we can. And, to reveal my undying optimism and belief in the power of LT&P, LT&P provides the required operational and philosophical (both!) way forward to make real progress. Virginia Woolf meets the Toyota Production System, giving rise to a consciousness of reality that recognizes the need to yoke ambitious aspirations with concrete strategies/tactics/practices at the most granular level.

Sometimes approaches are called “lean” that aren’t lean at all. That is annoying and problematic, often giving lean a bad name. But the opposite happens as well. There are countless cases of lean thinking being applied masterfully with the word lean (or the Toyota Production System) nowhere in sight. Lean thinking and practice, such as found at the core of programs such as J-PAL and GJI, embody the power and potential of lean thinking as a holistic approach to making things better for even the world’s thorniest problems.