“The Real Work of Management” webinar drew very engaged attendees who submitted hundreds of questions. That was many more than we could address during the hour-long live session in which Lantech CEO Jim Lancaster described the daily management system the company implemented when lean continuous improvement efforts stopped delivering great financial results.

So, we selected the questions that represented the major topics you wanted to know more about for a follow-up Q&A with Jim. Here are some of his answers:

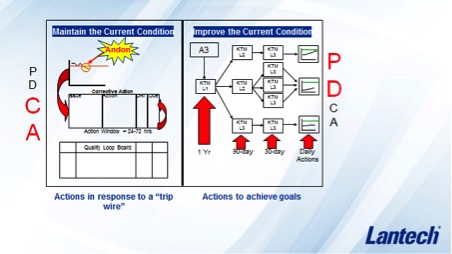

Q: Could you tell us a little more about the right-hand side of the action slide [slide 29 below]? One side has “maintain the current condition.” the other side has “improve the current condition.”

Jim Lancaster: The left-hand side is managing the standardized work of an area and the process. The right-hand side is where we manage either improvement projects in the area or projects in the area that are part of a broader, company-wide strategic project.

An improvement project A3 describes clearly what our objectives are, why we’re doing the project, and what the general plan — the A3 storyline — is. Then that breaks down into a series of key task monitors (KTMs) that break the work down into weekly chunks. By breaking work down, we know whether we’re on track or not, just like you know with the takt-time clock whether you’re on track or not.

Q: What’s the significance of the 30-day and the 90-day columns?

Jim: Level one KTM (L1 in above slide) is 12 months. The chunks of work that you’re trying to do are in deliverables by month. That’s where you’d plan out the whole project for 12 months. When you go to a level two (L2), it’s 12 weeks. You take the first three months of the level one KTM and you break it down into weekly chunks. You don’t do the ones farther out, just the next 12 weeks.

Then the level three (L3) is daily, and it’s the next 10 workdays. You don’t try to do the daily plan beyond the next ten workdays. You don’t try to do the weekly plan beyond three months.

Q: How do you switch from managing crises to tackling small variations in processes when major issues still happen?

Jim: There are two kinds of things when you’re managing problems. The first is managing to survive today and take care of the customer today. You have to do that on big crises, little crises — everything. When you’re clearly just trying to take care of today, that leaves you some time to do the improvement on root cause. What we try to do is do the root cause and solution in the area where we can get the biggest bang for the buck.

You’ve got to make sure we’re making the right thing for today, but in terms of the problem we’re going to chase back and make sure we never do it again, that’s going to be the problem right in front of me, so it’s easier for me to fix it.

Then tomorrow I fix the next one that’s sitting right in front of me. That’s just a very different view than trying to figure out the most important, biggest, hairiest problem and taking three months or six months to fix it. Meanwhile I produce 10 more big problems and then you never get out of the gravy yard spiral, so to speak.

Q: Do you teach structured root-cause problem solving to everybody in your plant?

Jim: No. We just teach it to the team leaders and the folks that are doing the improvements. Operators generally are not doing problem solving because they’re too busy assembling or welding or whatever.

Q: Are you trying to spread lean thinking to your supply chain?

Jim: I have tried in the past and utterly failed. I have not been successful nor have I seen anybody else who has been particularly successful with it. That’s why I’m in-sourcing.

Q: It seems that this system would be hard to implement if the whole business was out of control. Would you suggest any stabilization activities before going into your system of management.

Jim: If the managers doing the walk-around do not understand the work, the value of maintaining work, and how difficult it is for an operator to maintain work, then putting the system in place is likely to increase people’s frustration. You don’t have to necessarily install a pull system but you have to implement standardized work and problem solving to start.

If you don’t know how to problem solve and your management folks don’t understand how things get made and don’t understand the world that operators live in, then you’re not going to understand how to support then when you walk around. Walking isn’t going to do anything.

“If the managers doing the walk-around do not understand the work, the value of maintaining work, and how difficult it is for an operator to maintain work, then putting the system in place is likely to increase people’s frustration.”

Generally, you get your operation under control as managers and leaders actually learn the business. Once you have a critical mass of managers and leaders who know the business, meaning they understand how work gets done and the world their operators live in, then the management system can be really helpful.

If you put the daily management system in too soon, you get top managers who don’t know what’s happening on the floor. They just walk around and guilt trip the people who have red [abnormal] signals in their processes. They’ll pontificate about why they think the problem might be occurring.

The operators and the team leaders just roll their eyes because management isn’t really helping them. This system is set up to help, but if you’re not really helping then all you did was put a bureaucratic step that wastes everybody’s time.

Q: Does your line management use computer tools to update their own metrics or do you have a dedicated Excel expert or resource.

Jim: Neither. We use grease boards and dry-erase markers. Sometimes we get fancy and we use wet-erase markers.

We don’t use computers and Excel [to track metrics] because data becomes invisible inside a box. Pick metrics in the process where it’s easy, fast, and natural to do so.

The engineering types will try to use software to make everything look pretty and calculate out to the third decimal point and have a sheet of paper color-coded up on the board. There are some areas where the team leader does that because they’re doing it themselves that way and it’s quicker for them because that’s how they do it. I prefer grease pen because it is instantaneous and accessible.

Q: The book states that if an indicator exceeded a previously defined run-rate tolerance, the area manager would turn over a laminated card from green to red. What is the tolerance that is typically used to initiate action?

Jim: If there’s a problem, any problem, there needs to be a countermeasure to ensure that everything’s okay for today and no customers are affected. When the card flips — in most of our cases — it’s a red grease mark instead of a green grease mark. When that happens, then there’s an expectation that we go find out why we performed less well than average yesterday. There is no tolerance. Once you get a red, then you go look. The only reason you wouldn’t do that is if your quality loop board’s already full. If you’ve already got five quality problems you’re chasing, then we just ensure we’re good for today and we don’t do anything.

It’s not a tolerance issue. Once again, we’re not blaming or holding someone accountable or judging someone’s performance. That’s not what we’re doing.

Next Steps:

Benefit from Jim Lancaster’s lean journey. Learn how to detect and correct the “silent enemy” of lean continuous improvement – deterioration – in your processes.

- See the rest of this Q&A at LEI’s Knowledge Center

- Get The Work of Management

- Listen to the podcast