I almost skipped over the recent USA TODAY headline; “Toyota and Lexus Top List of Most Reliable Cars,” thinking there are three things you can count on in life; death, government dysfunction, and Toyota quality. After all, Toyota and Lexus have been at, or near the top of every quality list for more than 20 years. In fact, some people even see Toyota reliability as kind of boring – as if it were a knock against the company. That type of thinking indicates that the person doesn’t really understand what an astounding accomplishment this really is. Given the exponential growth in potential failure modes in today’s incredibly complex vehicles (advanced safety systems, infotainment, driver assist, powertrain, lights, and even the hundreds of mechanisms that enable doors and windows), and the highly competitive environment in which Toyota operates, this is an almost unbelievable accomplishment.

Reliability is fundamental to creating customer value. It means the product will perform as the customer expects, and it will do it consistently over time. It is essentially what quality experts W. Edwards Deming and Koriaki Kano were talking about when they described “fit for use” back when companies cared about such things. And the more complex the product, the more difficult this task becomes.

Begin in Development

There is no doubt that the Toyota Production System (TPS) and its focus on building in quality is a major reason for Toyota’s extraordinary performance in this area. However, it will likely not come as a surprise that their focus on quality starts long before vehicles are flowing down the assembly line. It starts in Toyota’s development process with a robust and proactive approach to designing in quality. To do this Toyota harnesses its formidable organizational learning capability to determine the likelihood that a specific design will experience issues in the field and design-in appropriate countermeasures. This system was eventually formalized as Mizenboushi and introduced outside of Toyota by Professor Tatsuhiko Yoshimura of Kyushu University.

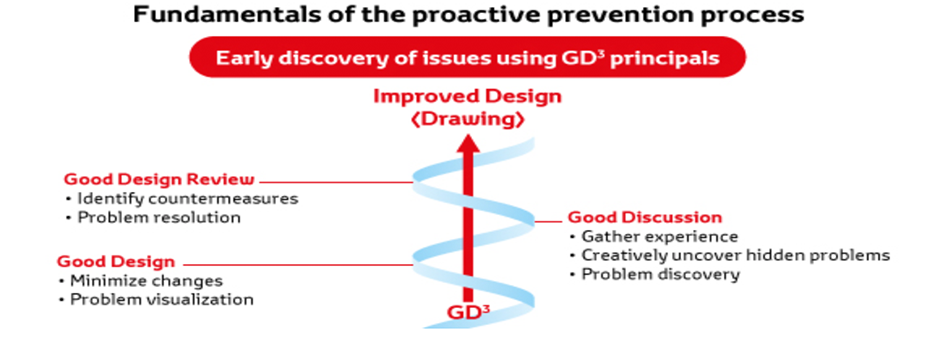

In Yoshimura’s book Toyota Styled Mizenbushi Method – GD3 Preventative Measures – How to Prevent a Problem Before it Occurs (JUSE Press Ltd. Tokyo 2002) he describes the three phases of the process as; good design, good discussion and good dissection.

Good design emphasizes creating robust designs by reusing proven components and proven design characteristics wherever possible. It also focuses on limiting the amount and severity of changes that impact a single subsystem. And finally,product features are designed such that they will make a budding problem apparent as early as possible. A bit like a smoke detector will chirp when the battery gets low.

Good discussion drives cross-functional analysis and debate especially focused on any new features, new parts, and all critical interfaces. The specific forum for this debate is referred to as design review based on failure mode (DRBFM) and prioritizes areas of potential risk. Yoshimura claims that this process is both more robust and efficient than traditional failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) because it is a more focused approach.

Good dissection is a method for analyzing test results that starts with a detailed review of any signs of unacceptable or inconsistent performance during testing. Parts from completed tests are dissected and closely studied for any signs of wear or degradation that might signal a potential weakness in design. Yoshimura also introduced a tool to help enable this process “design review based on test results” that enables debate and captures learning to further strengthen the mizenbushi system.

Ask Chief Engineers

In the research for our recently published book Designing the Future, my co-author Jeff Liker and I questioned several Toyota and Lexus chief engineers to understand how this process works at the vehicle level. Randy Stephens, the chief engineer (CE) for the 2018 Avalon and responsible for the vehicle’s overall quality, explained how all the individual engineering problem-prevention work was brought together at the program level.

This is how Stephens described the process: There are between three and four cadenced design quality reviews that take place a few weeks prior to every major milestone. At those reviews, each of the various engineering groups reviews their testing and documentation with the CE. These reviews may take place at the car, at the build or test site, and with the specific parts, depending on the topics to be covered. It often requires a couple of weeks for the CE to get through all the data generated from these reviews. The CE is required to sign off that the vehicle is at the appropriate level of quality relative to each milestone in the project. The final review is just before launch, and then requires a signoff on quality as well as safety as part of the “handover” to production.

So, it seems that extraordinary quality is not only designed into the product, it is designed into the development process itself. Designed in quality indeed. Perhaps the next time you might be tempted to minimize Toyota’s quality performance, you will think about what a significant accomplishment it truly is. But more importantly, I hope you will think about how Toyota’s principles and practices might help you design-in better quality in your products and processes.