In response to a recent Lean Post by Jim Womack, Fred Stahl briefly introduced a name that led to questions from a few of you. Charles A. Francis was a Yankee machinist who worked for Toyota Group founder Sakichi Toyoda for about two years in the early 1900s. Why is Francis important? Francis’ story is an integral missing piece to the larger narrative of the extraordinary exchange of continuous innovation in process technology that has taken place between the United States and Japan over the past 150 years.

Francis’ six years teaching and working in Japan, led him to numerous insights that will be surprising to many today, such as this observation about the raw state of Japanese workers in the early 20th century:

“I have found that the Japanese workmen …will never be able to do work that can compete with other countries if they are not trained – and trained properly”.

A Yankee Machinist

Charles Francis was a tool and model maker and machinist – a “mechanician”, in the parlance of the time – who for the most part worked at various manufacturers in New England, including the original Pratt & Whitney Co. in Hartford, Connecticut. In 1903 Francis accepted a curious invitation: to teach at the Higher Technological School of Tokyo (the modern-day Tokyo Institute of Technology).

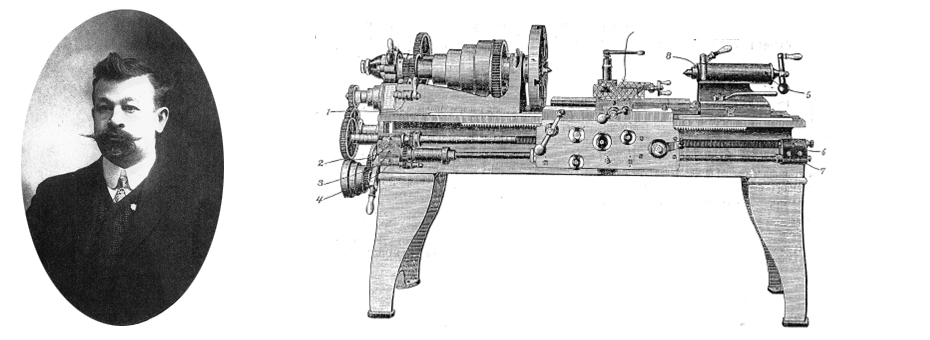

At the conclusion of his initial three-year contract, Francis extended his stay, but shifted his teaching responsibilities to part-time. Recognizing (in remarks made to engineering societies in Tokyo in 1905) that real learning take place outside the classroom. He began working part-time for industrial companies. In his first job, Francis worked two weeks per month at Ikegai Ironworks where he developed the first powered precision lathe in Japan, clearing the way for more high-volume precision metal working required for Japan’s soon-to-grow manufacturing sector.

Luckily for us, Francis wrote papers and made presentations during his time in Japan that provide valuable insights into his findings. He contributed at least three articles to the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers (JSME) in Tokyo in 1905-06. He also published at least three articles for The American Machinist, including an analysis of “American Tools in Japan” and a report on “The Tokyo Industrial Exhibition.” The third article concerned Francis’s experience teaching the American system of manufacturing and machining to Japanese managers and workers: “Lantern Slides for Shop Instruction – A Method Devised to Teach Japanese Workmen“. Together these pieces shed light on the state of work practices in Japan as seen through the eyes of an American possessing knowledge of the world’s best technology.

In early 1908, Francis began working for Sakichi Toyoda two weeks per month. His final work in Japan was for Japan-America Gramophone Manufacturing in Kawasaki, introducing the latest technology from the US – recording equipment from RCA – which required the highest level of precision machining available at the time.

In his presentations and writings, Francis emphasized key concepts such as:

- thorough maintenance of equipment and attention to changeover

- proper training of the workforce

- promptness and discipline

- creating a “model factory” to gather ideal practices in one location

- understanding manufacturing as a “system”

This looks like a list of principles and practices from your favorite lean production textbook. Especially fascinating to me was Francis’ emphasis on production as a system and the need to create a “model factory”. The approach of beginning with a “model line” or learning area is now well-established an important piece of a holistic strategy to lean transformation, espoused by Toyota’s Operations Management Consulting group and many others.

Francis departed Japan on May 31, 1910 from Yokohama on the Chicago Maru, arriving in Tacoma on June 14. This is just a few weeks after Sakichi Toyoda also left for the USA to study American loom technology at the gemba in New England, but we have found no record so far of Francis and Sakichi meeting in the US. Returning to his roots in New England, Francis worked as superintendent or foreman at a few manufacturers before landing at his final assignment, assisting the Remington Arms company with its major expansion in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1915 (the year that historic site expanded to 73 acres, employing at its peak 17,000 workers). Francis died at his Bridgeport home on Jan 14, 1916.

What can we learn about progressive change from Charles Francis?

The story of Charles Francis is remarkable because it sheds new light on the origins of the most important manufacturer of the last half of the 20th century: Toyota. Despite hundreds of books and many years of research, the role of one Yankee mechanic has been missed.

The early 1900’s were a time of upheavel for the textile industry in Japan and elsewhere—it was the largest industry in the world. The years Francis worked for Sakichi Toyoda (1908-09) were a watershed period for the Japanese loom industry as it shifted from narrow to wide width looms and from mostly manual to automated machines. Automation combined with the larger size required a major shift, from wood to steel. The strength of steel was required in order to withstand the stress on the chassis that came with the belt-driven power. That is why Sakichi needed Francis.

Francis knew machining, but in this regard, there is no reason to believe he was unique. Yankee machinists were scattering from New England – home of the world’s best machining technology. It is unclear exactly how he came to be invited to teach in Japan, but in this way as well Francis was not unique. Francis became part of Japan’s famous Meiji Era rush to learn western technology, under the slogan “Western Science, Eastern Spirit”. From the forced opening (by Admiral Perry’s Black Ships) of Japan after more than two centuries of isolation in 1858 until the rise of nationalist militarist in the 1930s, Japan continually dispatched hundreds of researchers and traders to countries that possessed leading technologies, such as the US, Great Britain, Germany, and France, and invited hundreds of technologists like Francis to share their knowledge directly in Japan. When Francis arrived, there were about 80 foreign expert instructors such as himself.

Luckily, many of Charles’ enlightening observations of Japanese workshops remain. In a presentation before the Society of Mechanical Engineers in Tokyo May 8th 1905, entitled “Mechanical and Industrial Lines in Japan and American Machine Tools,” Francis made these stunning observations:

“I honestly believe that the best plan for the government to adopt …would be to establish a Model Manufacturing Plant, and in this place the foreign instructors to teach the workmen, not only the actual working of the various machines, but also the meaning of ‘system’….

“In the development of this country in industrial lines very little success will be met with unless you overcome the idea, which I find so many of the manufacturers have here, of doing their work in the cheapest and poorest way… I have found them trying to make not only a cheaper article than their competitors, but doing their best to make it poorer, not only in the matter of workmanship, but also in the quality of the material used.

“In order to produce… high class machines, and to be able to sell them at the lowest prices, one must have a well-arranged shop system…, that is one of the secrets of the great success obtained by American manufacturers. This system is not adopted for the office alone, but is used throughout the entire plant, every man employed in the factory must be at his place ready for work right on the minute of starting, and keep steadily at his work until quitting time.”

Now, if you have been paying any attention to what has been happening in the global manufacturing arena over the past 50 years, those words are nothing short of incredible. The “Japanese management” boom of the 1980s extolled the virtues of the Japanese worker: disciplined, diligent, dedicated, exemplary by any standard. In fact, the Japanese worker, especially Toyota’s, became the global standard. Even today, I frequently hear observations such as, “We just don’t have the discipline of Toyota to be effective at standardized work and kaizen…” But, go back 100 years, when Japan – and Toyoda – was learning from the West, and we find an American lecturing the Japanese on matters such as punctuality, diligence, the necessity of organization, and a systemic approach to all work.

The lesson I take from this is an important one, one that is verified by the global diffusion of lean thinking and practice over the past three decades: culture matters, but never let stereotypical views of national culture or character be seen as an insurmountable obstacle or used as an excuse to not do the right thing.

Did Charles Francis Influence Modern Lean Thinking and Practice?

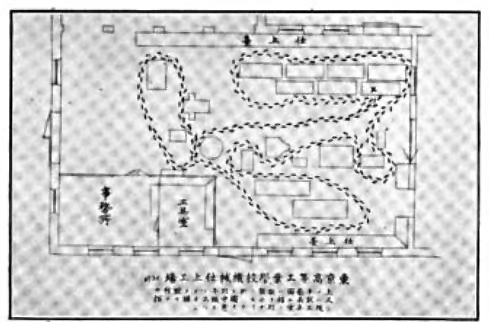

Francis’s direct influence on lean production is hard to gauge. Sakichi Toyoda clearly felt Francis’s contribution was valuable. Sakichi paid Francis 500 yen per month, almost double the wages Francis had received from Ikegai, an amount that Sakichi only managed to pay by contributing half from his own salary! More importantly, Francis’s teachings (see the bullet list of key concepts above) have clear resonance with Toyota Production System principles and techniques. In the “lantern slides” he created to teach Japanese workers when away from the gemba – visuals are better than just words, he observed – Francis shows what is surely the oldest “spaghetti diagram” in existence.

It is interesting to speculate about Francis’ influence. Francis’ stint at the University of Chicago coincided with the tenure there of John Dewey. Dewey’s influence on American thinking, from his pragmatist philosophy, to his formulation of the scientific method, to his specific ideas and activities in the realm of education (Dewey believed that “thinking” and “doing” should never be separated in education), all have resonance with what we know of Francis’s work in Japan and with fundamental characteristics of what later came to be known as Japanese management and with the Toyota Production System itself.

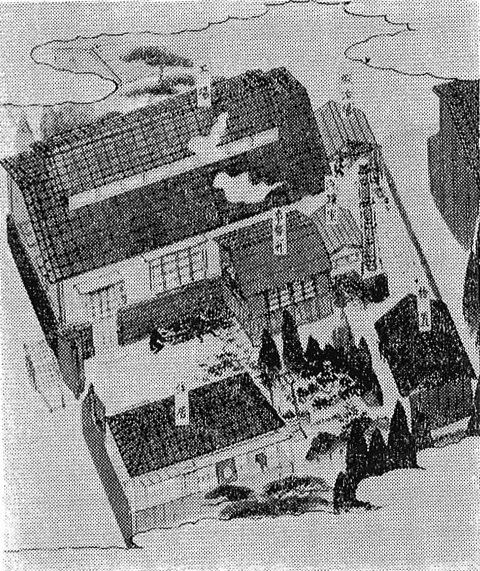

It would be a mistake to overstate Francis’s importance. If his influence on the Toyota Production System was great, Francis would not have gone “undiscovered” until now. Still, regarding his direct influence on Sakichi Toyoda (and the later Toyota Motor Corporation), consider this statement from one observer who was in a position to see it unfold first-hand (from Memories of Ikegai Kishiro, the founder of Ikegai Ironworks):

“Charles was able to build the factory of his dreams (omou toori) with Toyoda-san, compared with what he could do with Ikegai. I think the factory Charles helped Sakichi build was the first mass production (volume production) factory in Japan.”

Toshiko Narusawa, my co-author of Kaizen Express, and I have been researching about Charles Francis for the last five years, tracing his early 20th century footsteps through New England and Japan. We searched far and wide to uncover what we have learned so far and look forward to reading Fred Stahl’s upcoming book Worker Leadership: America’s Secret Weapon in the Battle for Industrial Competitiveness, to be published by The MIT Press in September 2013. A community effort may well unearth further information and a community dialogue will absolutely yield further insights. View a complete timetable of Francis’ life as a mechanician (let’s revive that term!) and teacher in the US and Japan, revealed here for the first time.

Please leave your comment below to continue the conversation!