Learning is at the heart of lean, which is more accurately described as an education system rather than a production system. And yet after decades of research and practice, lean is often perceived as the latter rather than the former. By now all of us in the lean community realize that behind all the tools for operational excellence and the different management system needed to support their use, lies a much deeper challenge: to develop the human potential of everyone to create a culture of accelerating continuous improvement to meet today’s changing circumstances.

That’s why I’m excited to have written the introduction to a new book The Lean Sensei, which dives deeply into the role of experienced, expert, masters in preserving and sustaining the spirit of lean. The following excerpt from this book shares five ways that sensei improve how organizations deliver value while also discovering the facts of the situation now and in the future.

Contrarily to consulting, training or coaching, the sensei doesn’t have to know the answers (why would she? this is a discovery exercise) but she does have to have a good idea of where to look. In practice, the sensei will:

- Take you to the gemba: take the leader to the real place where customers use the service and where frontline staff do the work in order to observe firsthand what is really happening as opposed to what it says on the PowerPoint slides and what we believe is happening. The sensei’s first role is to maintain the dialogue with reality by looking at specific, detailed cases of failure to delivery, such as customer complaints, rework and late deliveries. Go and see is not simply about observing, but about grappling with concrete problems to grasp what constraints apply and how solid they really are – in order to understand the problem more deeply.

- Discuss what the real challenges are: business conversations are implicitly oriented towards goals (here’s where we want to be) and plans (here’s what we need to do). The sensei’s role is to question the implicit assumptions in these instructions by trying to get people to agree on the problem before arguing about solutions. This is mostly an exercise in logic: clarifying the causality of both what the goals really are – often contradictory and unclear – and how the plans can get you there – often a dotted line built on beliefs, faith and wishful thinking rather than logic. Rather than say “I disagree,” a sensei will say, “I really don’t understand how doing this will deliver what you intend.” The sensei’s job is to clarify the main challenges that the company needs to face to thrive, rather than help implement ready-to-use solutions.

- Prescribe exercises: real learning is not an “aha!” moment of clear understanding with a life-changing before and after. Real learning emerges from familiarizing oneself with a new thought or practice until it becomes natural. To help people explore what is off the table, the sensei will give concrete exercises, such as “5S” or “measure lead-time” or “stop at the next doubt on quality and have a look.” These practical exercises are described extensively in the Toyota Production System and are meant to get leaders and their teams to learn by doing through discovering a difficult issue in concrete, detailed cases. TPS tools are not instrumental tools for random improvements but specific exercises to analyze and solve recurring problems, linked to key business challenges. SMED is not about reducing tool changes, it’s about learning to run shorter batches, something no one is at ease with in the way our organizations are designed for delivery at the lowest unit cost. The exercises don’t have a predetermined answer – again, this is discovery, not delivery – but the people themselves will discover their answers through carrying out the exercise repeatedly.

- Teach PDCA: While exercises are there to develop awareness, thoughtfulness, depth of thinking, is just as important. Thinking deeply means going beyond the fast reaction of memory and engaging the slow thinking processes of considering ideas against what we see and know and kicking them around. It’s hard – both personally and socially. To really understand something, we have to try to change it – the commitment to change is what gets us looking seriously at an idea, and examining how reality reacts. In its internal manual to On-The-Job development, Toyota describes itself as a sum of PDCA cycles leading to “long-term prosperity and growth as an organization.” The main guideline to think deeply is Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle: clarify a change you plan to test and why, do it in a limited way, on a small scale to see what happens we you carry it out, check the impact, quantifiably if you can or looking very carefully if you can’t, and act upon it, decide whether you want to adopt the change, adjust it or abandon it. Because motivated thinking is dominant, most people do plan/do, plan/do, plan/do and never check/act. The sensei is there to make sure the PDCA cycle is carried out in full so that people actually think and not stay satisfied with their quick responses.

- Push you on to the next step: Sensei never seem satisfied with what you’ve done and are always asking: What next? Hajime Ohba, a long-time Toyota sensei with suppliers in North America, explains that “True North” thinking always concerns what we need to do, not what we can do. His approach is typical of what we’ve seen others sensei do: Think deeply on what you see on the gemba and try your idea immediately; Do small and gradual experiments to relate the method to people’s work. Always ask the question “What’s next?” Don’t dwell on how much better we are but how much farther we have to go. This sums up an approach where thinking can only be done by doing, and where learning occurs when you go beyond the first, or even second attempt to explore the really new and unfamiliar. It’s not that the sensei is “never satisfied” as many people feel it, but that the sensei is looking beyond the horizon of what is currently known, for that new practical idea that will break the back of one constraint and open a new space for improvement.

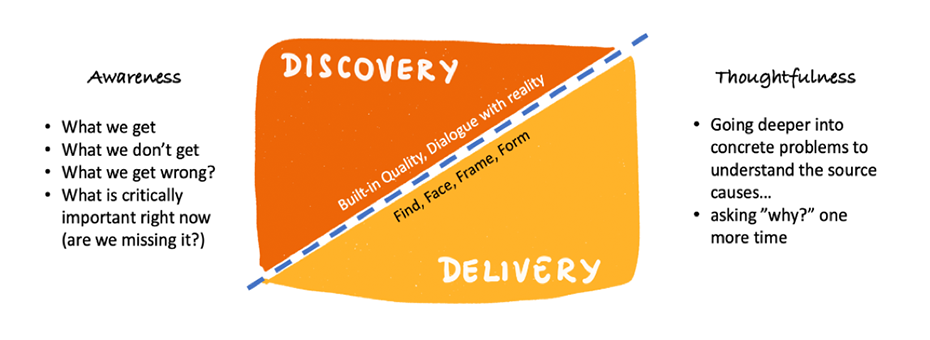

The sensei’s direct contribution to value lies in showing the relationship between delivery and discovery and making sure the balance stays… balanced.