Ten years ago this month, Michael Ballé launched the Gemba Coach column. Initially conceived to help introduce the ideas in The Lean Manager (co-written with his father Freddy), Michael has continued to write this regular column (349 to date) while producing books such as Lead with Respect, The Lean Sensei, The Lean Strategy, The Gold Mine Trilogy Study Guide, writing numerous articles in other outlets, actively helping companies implement lean, and co-founding the French Lean Institute.

As one of the two editors (along with Chet Marchwinski) supporting the ongoing production of this column, we are sharing a selection of the most popular and notable columns over the years, organized by a few general conclusions about lean drawn from the work.

Fundamentals (not orthodoxy) matter.

From the very first column Michael has consistently tied his advice to a faithful application of core Toyota Production System (TPS) principles, without demanding a mindless conformity to established practices or to commercialized frameworks, models, or any other packaging of the TPS dynamics as a product. (TPS veterans occasionally differentiate between the formal definition of TPS and the generalized performance elements of the system itself.)

Over the past decade he has worked diligently to reveal the “why” driving the “how” and the “what” of established lean practices, detailing how to pursue these methods while rigorously delving into the reasons behind the reasons.

In his column on Why Does One-Piece Flow Matter?, for example, Michael carefully explains the importance of having one (or zero) parts in process versus having, say, three (or any other number). One/zero parts in process supports flow, which in turn reduces lead-time; and the resulting tension in the line boosts operator engagement by exposing kaizen opportunities as they emerge.

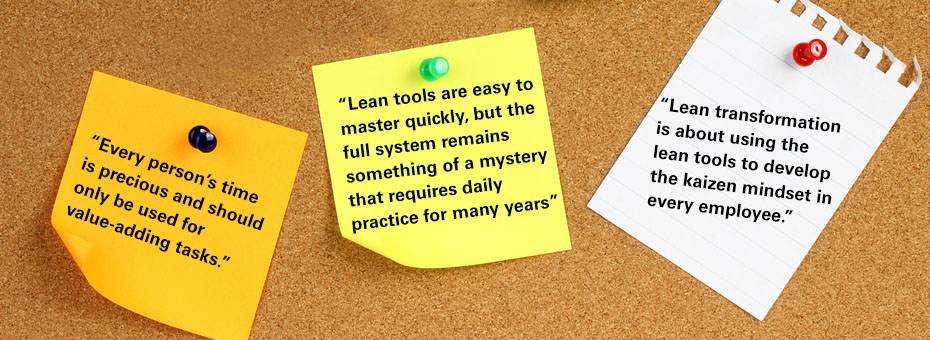

“The basic thinking is that if you reduce lead-time in a process you will satisfy your customers better, and you will reduce your cost by getting closer and closer to the minimal capacity required to deliver. In doing so, you learn better how to make things. The other key insight is that every person’s time is precious and should only be used for value-adding tasks.

Lean Practice is A Complete System—Far More Than the Sum of its Tools

Gemba Coach kicked off with 5S Again and Again and Again, in which Michael delved into 5S as a fundamental tool in the lean kit, emphasizing its role in both the short term as a wake-up call for suboptimal working conditions; and its broader long-term function supporting the “twin notions of standardized work and kaizen”.

The discipline of creating and maintaining order in one’s workspace does more than satisfy a Marie Kondo jolt of “spark joy,” he argues: “Lean transformation is about using the lean tools to develop the kaizen mindset in every employee, as opposed to applying the lean tools to every process to get a quick boost.”

“Lean transformation is about using the lean tools to develop the kaizen mindset in every employee, as opposed to applying the lean tools to every process to get a quick boost.”

In other words, when you lose sight of the systemic benefits that instrumental tools deliver to the broader system of learning and improvement, you start down a path of unsustainable point optimization and inconstancy of purpose.

As he notes in Should We Have Our Own TPS House?,“The one consistent feedback on translating TPS into other companies is that first, companies pick and choose which aspects they think will work for them, and ignore the others. You can see this easily by comparing how often just-in-time is attempted or written about to how rarely jidoka gets mentioned.

“Secondly, firms will ‘adapt’ the tools and principles to make them more palatable to the local culture. Most plant managers will actually argue this point vehemently.”

Similarly, in Are You Pulling?, he notes that “Lean is a system. Standardized work cannot be considered in isolation from customer satisfaction, JIT, jidoka, and kaizen. In fact, when you look at how people often go about designing standardized work, they tend to jump in with the stopwatches to define the optimal sequence of work, skipping the very first box to fill in the form: takt time.”

Transformation is Neither A Fixed Destination Nor A Simple Deliverable But A Modest, Humble, Daily Process

An underlying sense of optimism about the power of lean to bring joy and prosperity in the workplace runs throughout this work. And yet, the author mitigates the promise of Enlightment by focusing on the profoundly challenging daily work of simply paying attention to the right problems and working with others to tackle them mindfully. Lean is presented as both a tremendous opportunity to produce joy while at the same time revealed as a humbling, daunting, grind marked by countless setbacks and painful lessons.

In Am I Doing Lean Right?, he shares three simple criteria for gauging success: fostering a true intent to practice lean, marking visible performance improvements directly linked to individuals finding a way to do their work better, and a deepening of one’s personal understanding and practice of lean. All are ultimately tied to one’s own link to the process of improvement and the ongoing discipline of working mindfulness. He adds:

“Lean, to my mind, is a full paradigm change. Individual tools are easy to master quickly, but the full system remains something of a mystery that requires daily practice for many years.”“Lean, to my mind, is a full paradigm change. Individual tools are easy to master quickly, but the full system remains something of a mystery that requires daily practice for many years. I was recently in Toyota’s Taipei plant and asked them: how long does it take to develop a TPS sensei? The answer: 30 years. I don’t believe they’re being cute – there is a reason. The lean system has grown over 60 years in a variety of situations and mastering it is a life-long pursuit. As a result, I do believe that any activity (successful or not) should also deepen your understanding of lean itself.”

Lean principles apply to all enterprises.

Once more threading the needle by finding the common ground between, in this instance, the specific applicable “rules” of lean in one setting, and the deeper principles that apply in any system of work, Michael seeks to apply takt time to his production of columns. In How Do You Apply Takt Time to Service Work?, Michael provides a clear definition of takt and then shares how thinking “upside down,” or responding to pull, enforces a healthy tension and requires flexibility in his work. He adds:

“And the same is true of Toyota. Calculating takts and running plants accordingly has given them superior understanding not just of how to run plants, but how to understand customer demand in different markets—and knowing where to put options on all cars (say, air conditioning) and where to cancel options (say, ashtrays) –or not. Takt time thinking brings you close to understanding real customer demand, not just in volumes, but qualitatively as well: why do products sell faster than takt? Why do products sell slower than takt?”

In another piece about lean practice beyond the factory floor, How Do Lean Concepts Apply In An Office Environment?, Michael highlights the value of establishing clear and visible common goals linked to customer demand and to employee values. He counsels office workers to create simple visual plans that reinforce good behavior and invite suggestions for improvements.

Lean is a Learning System to Continuously Develop People

If there’s one core message tying these columns together, it would be a deeply humanistic push framing lean work as a system of tools and ideas designed consciously to engage every individual in everyday problem-solving for greater innovation in order to deliver more value to the customer. Michael has repeatedly and consistently addressed this topic.

Many columns seek to clarify how the abstract topic of “respect” translates into tangible practices and action-able behaviors. In How Do You Define Respect for People?, he offers the suggestion that finding specific ways to link specific performance into visible improvement realizes this goal: “make every effort to understand each other and take responsibility for others’ problems, develop every person’s problem-solving autonomy, involve every person in designing their own jobs and managing their own work and partake in the joy of create when ideas become a reality.”

Defining kaizen as “the opportunity for humans to be creative and display this creativity” in Does Respect for Humanity Mean the Same as Respect for People?,he closes with a statement that speaks to the heart of his work: “Respect means seeing the potential in every person and working hard at creating the conditions for this potential to realize itself, which means designing a working environment ‘natural’ for humans to work, think and be creative, rather than one that constrains humans into behaving like soulless robots.”

“Respect means seeing the potential in every person and working hard at creating the conditions for this potential to realize itself.”

Commit Deeply, to the Long Haul, and Achieve Your Large Strides Through Many Small Steps

Over the course of a decade, the column has managed to tread both the low and high road faithfully, ranging from topics such as defining standard work for senseis, applying andons to software development, exploring the spiritual dimension of lean, and emphasizing problems rather than solutions. The cumulative effect of this work calls to mind a quote from the final chapter of The Gold Mine, in which the main character reflects on lean.

“Rationality did not lay in higher reasoning powers, in visionary schemes, but in the ability to narrow down problems until one reached the nitty-gritty level at which one could actually do something about them. The rest is philosophy.”