Editor’s Note: This article, updated in March 2022, is the first of 3 focused on exploring the crucial role standardized work plays in a lean enterprise. Read the second and third articles in the series.

So, how is your standardized work implementation going?

Responses to that question usually paint an ugly picture. Here’s what I frequently hear:

- “We just don’t have the discipline Toyota has to make standardized work work.”

- “We put it in place, but the people don’t follow it.”

- “We have trouble transferring good standardized work from one worksite to another.”

- “We are good at determining the One Best Way, but people always insist on doing it their way.”

- “People just don’t want to follow it. They like to do their own thing.”

- “We put in an audit process, but the auditors don’t follow the audit process.”

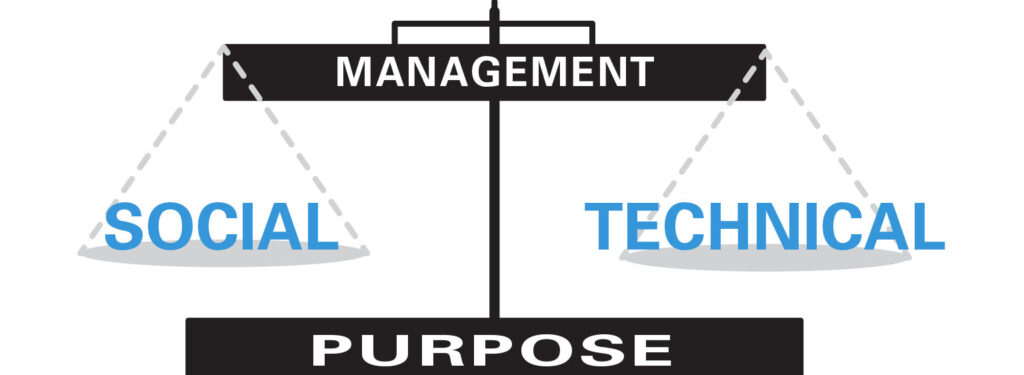

I like to say that the Toyota Way is a socio-technical system on steroids. A test for all our lean systems is how well we integrate people with process (the social with the technical). Nowhere does that come together more than in the form of standardized work and kaizen.

By that, I’m saying much more than just pointing out that our corporate-level lean initiatives should involve both Engineering and Human Resources departments, each initiating programs to elevate the technical and the social dimensions of work. I am talking about how work design simultaneously embodies both dimensions at the micro-level. When a worker bolts in the seat belt in the factory or an office staffer processes a requisition in the office, the work will be driven by both the technical and social aspects of the job design.

Leaders, be warned: You cannot simply dictate this from on high. You are in trouble as soon as you find yourself chasing compliance in pursuit of standardized work. You are chasing your tail, and you’ll never catch it. Rather than controlling compliance details, examine why the worker does not follow the standardized work. Ask, “Why can’t you follow the standardized work?” The answer to that question — asked not accusingly but in a spirit of pure inquiry — will invariably lead you to unexpected places, usually quite far from the employee.

Understanding Standardized Work

In this series of Lean Posts, I’ll first present five neglected, misunderstood, or forgotten aspects of standardized work. Then, we’ll explore how to think about standardized work for non-standard work, things like service industries, knowledge workers, creative work, and management. Finally, I’ll provide a kind of “outline” that might help as a guide for you to think about establishing standardized work in your organization, centered around these five neglected aspects of standardized work:

- Don’t confuse standardized work with work standards.

- Don’t confuse standardization with commonization.

- Don’t impose standardized work without providing a structured improvement process — a clearly defined, unambiguous means of improving it (kaizen).

- Practice, practice, practice.

- Don’t forget the critical role of the leader/manager.

1. Don’t confuse standardized work with work standards

As a practical matter of getting started with standardized work, you must first clarify your work standards. Never confuse work standards with standardized work. Other terminology often used for “work standards” includes “quality standards,” “specifications,” “engineering specifications,” or “quality specifications.”

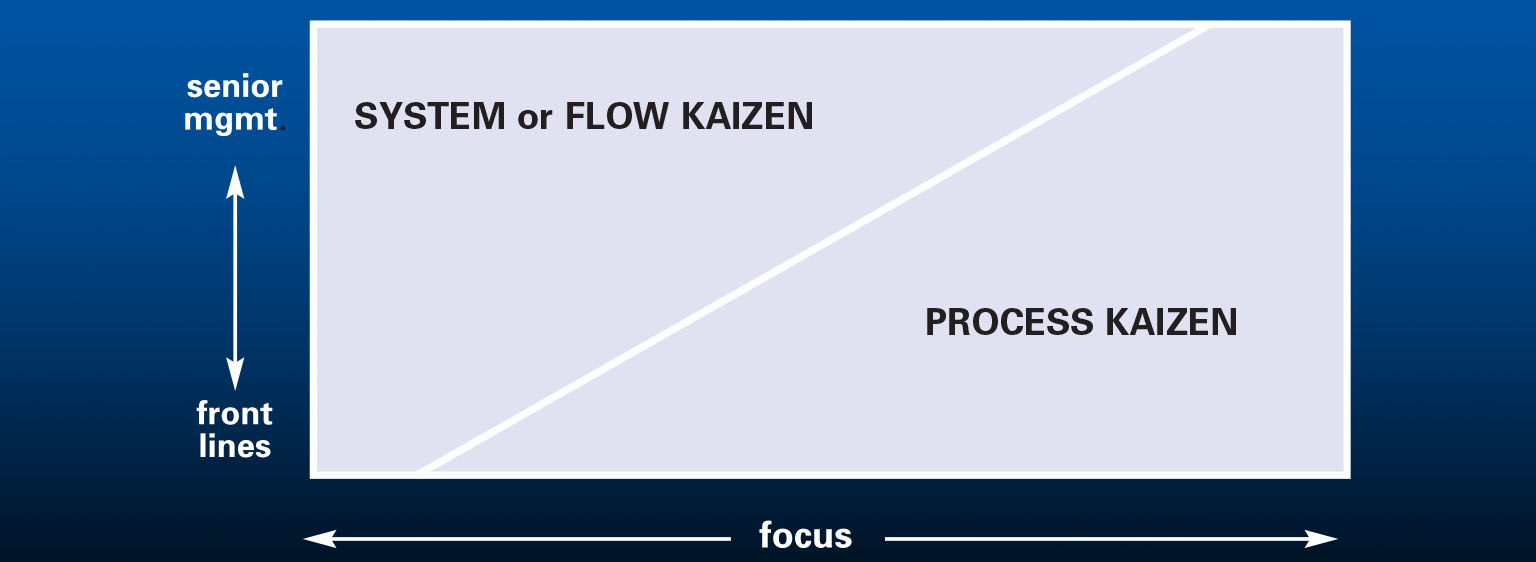

Work standards are established during product and process development. They comprise the work that must be accomplished for the product to be produced to achieve the product’s or service’s design intent. Changes to work standards require an engineering design review, so manufacturing companies usually have an “Engineering Change Request” process in place. (And, by the way, it’s also a process that is often full of problems and waste, and so is a good process to choose for one of your first efforts at business process kaizen). So, in standardized work, Toyota usually calls work standards “Quality Standards.”

Some examples include:

- Assembly – apply xx pounds of torque

- Processing – heat treat at xxx degrees for x hours

- Healthcare – provide xx medication at xx dose

- Coffee – xx seconds for an espresso shot

- Journalism – a weekly column of xxx words

For each of the above, kaizen (improvement) is also possible, but through a different process than the typically incremental improvements of standardized work and a suggestion system. Those are work standards.

Toyota-style standardized work for the frontline production operator is a matter of three basic elements: (1) timing, (2) sequence, and (3) a standard amount of stuff that is in process at any given time.

- Takt time and cycle time (TT vs. C/T): In other words, timing — the timing demanded by your customer and the timing constraints of your processing capability

- Sequence (including layout and man-machine combination with process capacity sheets and standard work combination table): In other words, determining the optimum order of producing the product or service — first do A, then B, then C

- S-WIP: In other words, the amount of in-process “stuff” that is required, no more, no less. That stuff may be material, parts, or information.

With those standards established, the operator has the essential elements to make it possible (with training, practice, and support) to complete the work successfully. From there, the operator can easily learn to identify problems. And from there — with proper training and support — can solve problems and make improvements. Finally, with the standardized work in place, now the operator can do plan-do-check-act (PDCA) problem-solving.

Toyota’s “Mr. Standardized Work,” Mr. Isao Kato, has hammered this point for many years: “Before you can begin with standardized work, you must clarify your work standards.” Too often, this edict has fallen on deaf or not-ready-to-listen ears. This distinction is fully institutionalized in Toyota production operations, so Toyota operations people hardly even need to concern themselves with it. At your company, you will probably need to do a lot of detailed work to make the distinctions clear, and you may need to add “required output” to the list for a fourth basic element of work standards.

2. Don’t confuse standardization with commonization

Standardization means a given operation has a standard practice or routine that must be followed and serves as the baseline of comparison that the individual doing the work can use to discern normal from abnormal. With that baseline, a foundation for PDCA is established, making improvement possible.

Commonization, on the other hand, means that a given operation is done the same way everywhere, which is where concern with “best practice” and seeking “one best way” comes in. Toyota refers to it as yokoten. For example, an assembly job that entails bolting in a seat belt or the process for communicating a scheduling change in a dentist’s office — commonization is doing those jobs exactly the same in every location by every worker. (See my “Teachable Moment” column.)

Our aim with standardized work is the former: the establishment of a baseline of operation from which improvement is possible. There are, of course, many occasions when commonization is also desirable. But, the real prize here is getting each person to follow their standardized work so that every time they do the job, they do it in the same way. Then with that baseline, they can observe the process for correctness, easily identify abnormalities, and readily generate improvements.

As a leader, if you can achieve this in all your operations, you should be very happy. Of course, then, you may also wish to pursue commonization as needed. But, my wager is that once you have each worker engaged in pursuing improvements in his or her own standard work, you will find your dissatisfaction that different workers may do similar jobs a little differently to be much less of a concern.

Many companies allow this concern to become an excuse for not turning their employees loose with kaizen and not charging them with making suggestions to improve their own work. Instead, such managers choose to worry about keeping track of and communicating “best practices.”

My bet is that if you do unleash the creativity of your people, you will quickly stop worrying about the fact that worker A in plant B may perform the operation a little less efficiently than worker B in plant A.

3. Don’t try to impose standardized work without providing a structured improvement process, a clearly defined, unambiguous means of improving it (kaizen).

You will have no or limited success with standardized work unless you also institute a process (whether or not labeled formally as a “suggestion system”) that gives individuals doing the standardized work a way to make suggestions in how to improve the work — kaizen. The essence of kaizen comes down to the people who do the work making suggestions on how to improve it. In other words, you can’t do standardized work without kaizen, and you can’t do kaizen without standardized work.

What is Standardized Work? What is Kaizen?

Standardized work and kaizen are two sides of the same coin — if you try to have one without the other, you will encounter one of two types of serious problems. To explain and explore:

Standardized work without kaizen:

- Employee motivation is killed, human creativity wasted

- Problems repeat, unidentified, unsolved, and unabated

- Employees don’t take the initiative, so improvement stops

- Operations — like economies, like companies, like cultures, like species — either progress or decline.

Kaizen without standardized work:

- Chaotic change, the saw-tooth effect of progress and regress

- Problems repeat, PDCA not followed, no root cause analysis

- Progress that is impossible to identify, improvement stops

- Kaizen, an expression of the scientific method, requires a baseline of comparison.

These two sets of problems bring us back to the thesis I’ve been hammering in this space for months: The technical/process and the socio/people sides of the standard work equation are equally important. Separate them and expect to find trouble.

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

Gain the in-depth understanding of lean principles, thinking, and practices.

Great 👍

Clearly describes Standardised work and work standards or quality standards

Thanks for sharing!

Great for emphasizing the need for continous improvement as a key element to make sure standardization is adopted