I often wonder how people know what they know. I’ve sat through years of formal schooling and done most of my learning in the classroom. But the older I get, the more I wonder, did I really learn what I needed to learn?

When I was doing my MBA, I was part of a multi-disciplinary lean team in a hospital emergency department. With a consultant coaching me, I asked myself where I felt like I learned more—in my masters course or on the floor with my colleagues. I wasn’t sure. Fast forward a few years later and I spend almost 100% of my time on the floor, totally without a classroom. Sometimes I’m coaching and sometimes I’m being coached, but I’m always learning. One coach sticks out among the rest.

Having NUMMI and TSSC roots, I’m confident in Coach’s teaching abilities. But most interesting to me is what Coach doesn’t do. I’m used to grades and KPIs that tell me something about my performance. But with this coach, I don’t have those things. So, how do I know I’m progressing?

During a visit with Coach to a customer’s manufacturing line recently, I learned an important lesson about experimentation. Scrapped units are a big problem at this particular plant. I’d been working on a line problem for a few days that was linked to scrapped units, stepped away from it for a few weeks, and returned to find that the line orientation had changed. My previous countermeasure (inserting a laser to show the available/allocated space for a hot gas loop) turned out to no longer be helpful to the team I’d been working with.

At first I was disappointed to see the laser laying lifeless on the floor, no longer needed at the repair station. Why didn’t someone reconfigure the laser to be adjusted to the new line? For a few hours I contemplated how to use the laser with the new layout. Surely, we’d go back to using the laser!Upon seeing me struggle, Coach asked my rationale for reinstituting the laser. “Really?!” he asked. I stood there stunned, unclear as to what he was getting at. Then I realized I must not be on the right track. He told me I had one hour to think and he’d be back.

Coach left to work on other things and there I was, left to contemplate my next move. You’d think a coach would be there to help me, show me how it’s done, but I know better than that by now. This isn’t how coaching works. And based on Coach’s inflection and tone, his shock at my going back to the laser, I knew the laser idea didn’t just need to be adapted, it needed to be thrown out. But why?! Well, for one, it was too hard. I’ve learned through trial and error that good countermeasures shouldn’t be so hard. With the operator (let’s call her Linda) by my side, we brainstormed new potential countermeasures. With every idea, I heard Coach in my head saying “Really?!” Who knew one word could be so helpful!

Our confidence was high when Linda and I came to an idea that sounded reasonable to both of us. If the hot gas loop is not within 90 mm window of clearance, it gets crushed at the next step in the process and the unit needs to be scrapped. With Linda’s hands already touching the unit, how might we capitalize on that particular step of the process? A small tapping movement to the side of the product would keep the piece in place. This was almost too simple. Better yet, this added work required only an extra .17 seconds and the operator would still be within takt time.

|

| “go/no go” jig created to make sure things were in place |

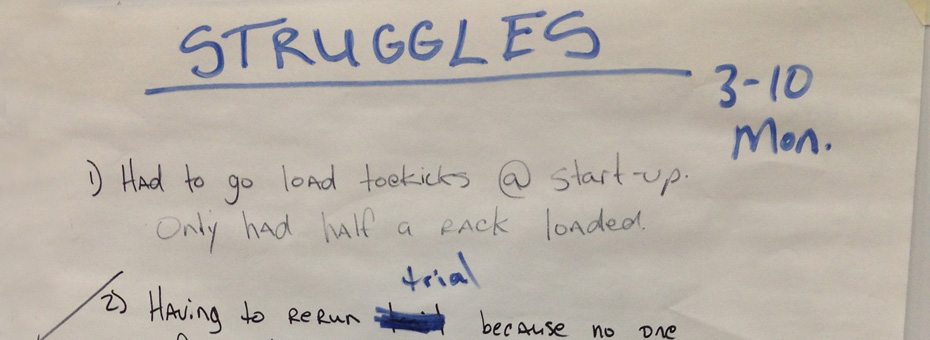

As Linda did her work using the new process, I stood by her side as quality check, watching each unit pass down the line. I knew the dimensions of clearance needed for the next phase on the line. I carefully inspected each and every one of the units using my eyes to see if it was within the window and a small “go/no go” jig created to make sure things were in place, if needed. Later that day I walked over to where the scrapped units were kept. To my dismay, I saw what looked like one of my experiments! I called Coach over to look at the unit. Unfazed, he felt the back of the unit, running his hands over the damaged area. I began to blurt out frustrations over my failed experiment when he stopped me, and said, “How do you know this happened during today’s shift?” I thought for a moment and with a puzzled face answered, “Well, I was standing there the whole time… I watched every one of the units go down the line with my own eyes and made sure that things were happening at they should be.” He continued to push. “Are you 100% sure this happened on today’s shift?”

For the first time in a while, I actually thought before I spoke. Could this unit have been put on the line further down from where I was standing? I didn’t actually know because I hadn’t tagged the units. When he saw that I wasn’t answering, he asked “How do you know your operator was the last person to touch the unit before it went into the machine?” He got me again! I didn’t know. Though I was watching the units, standing next to the last operator on the line, there was an on/off ramp where a team leader could pull a unit for repair or add a repaired unit. I wasn’t paying attention, nor had I considered the possibility of interference.

What do I make of all this? I was so concerned with running experiments, I didn’t think about the plan (the P in PDCA) of running an experiment. I didn’t define the objectives, nor did I think about the important variables. I had just jumped to a hypothesis and ran with an idea. With none of my units tagged or labeled as experiments, I would have never known which experiments were mine and which were added by others later. I also didn’t know when the first and last unit came out of the machine, nor the order. How often do you rush to get to the “do” phase of something without really thinking through your plan or truly grasping the current situation?

Here’s why I appreciate Coach. He knows to let me struggle through problems and even poorly planned experiments so that I too can learn the importance of planning. Does this approach work with everyone? I’m not sure. I think it might be something you’re eased into. But what makes it work for me? I think it’s tenacity. I want to prove to Coach I can figure out the problem. I like that he doesn’t swoop in and give me the answer. The small hints only fuel the fire to learn. There would be no fire if somebody gave me all the answers.

Earlier this year I had an interesting conversation with LEI’s John Shook. He said “A real funny difference is what Americans and Japanese will say when you ask them to evaluate training that they’ve just completed (an ‘exit survey’ if you will). Americans, if they liked the training, will say, ‘It was great, it was so much fun!’ as a form of praise. But, for the Japanese, the highest form of praise is, ‘It was excellent training, it was so tough!'” (Read more about learning differences between the East and West at NPR).

I’m beginning to understand the feeling. When I work with Coach, I hate it in the moment. It’s just hard! I struggle. I have to think deeply and then think again. I’m no longer the person standing at the front of the room with all of the answers. But in the end, it’s so much more effective and rewarding.

What happened to our experiment on the line? Well, it was a success. The hot gas loops continued to make their clearance and Linda and I had learned an important lesson about experimentation, too. Though having a thorough plan was one factor, thorough observation (seeing what’s really happening with clear eyes, without preconceived notions or assumptions) was the bigger factor. And while we struggled, I remember Coach was focused. No panic, no frustration, just focused on asking the question, “What do we know and how do we know it?” I’m due to return to the plant next month to see how the units are faring with our latest countermeasure. I’m still thinking about the tactics Coach uses with me and how they help me learn.