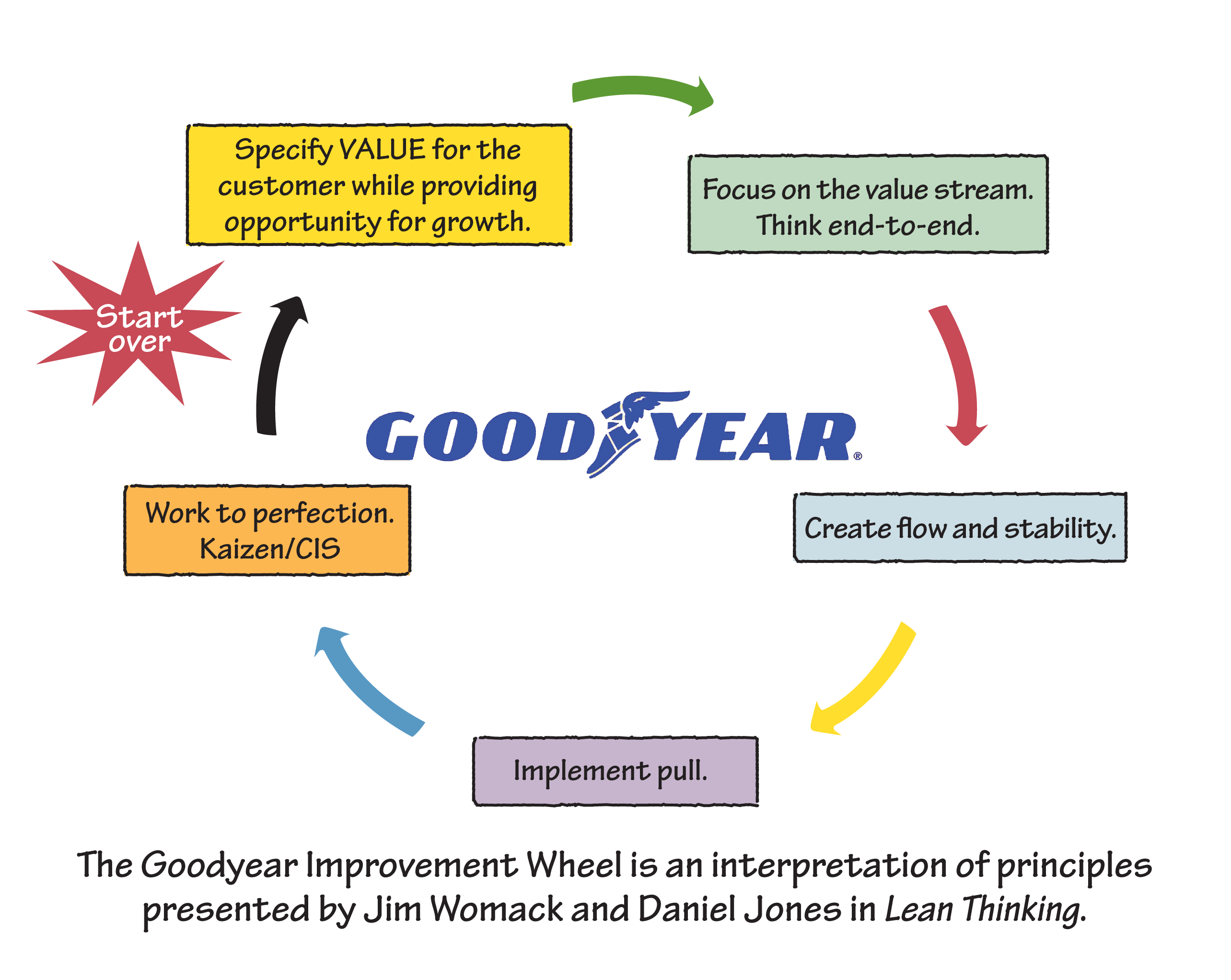

I once told Jim Womack that we had structured Goodyear’s application of lean principles in R&D according to the lean thinking steps that he and Daniel Jones presented in Lean Thinking, initially calling this approach the “Womack Wheel.” Jim looked surprised, and said he did not know he had wheels.

In Goodyear’s early lean training we taught the five-step sequence of lean thinking as presented by Jim and Dan, and then a colleague suggested that I align the content of my random Lean 101 training material with those steps. In 2005, my engineering colleagues and I believed that lean was the right approach to help fix our most pressing product development issues: huge delays in getting projects to market, missed business goals, and frustrated engineers. Nonetheless, we were still at a loss for how to apply lean to product development and prove to the organization that it could improve our complex innovation value streams.

Since our lean team was familiar with the five steps, we figured the progression could work as an implementation model. We turned the steps into an endless circle (after all, we make tires at Goodyear), and began moving around the Goodyear Improvement Wheel:

- Specify value for the customer: We started by figuring out what our customers (external customers and internal customers) wanted. To no surprise, they wanted everything, but they most wanted products delivered on time. Our objective was to give customers the best and most timely value possible as long as we also were consistent with the goals of the company (i.e., satisfy customer demands but not at any cost or be deviating from key corporate objectives).

- Focus on the value stream: We went to the gemba to physically see the end-to-end value stream. Like many starting lean, this was new to us. Our mission was to understand how R&D and other contributors and stakeholders (marketing, manufacturing, procurement, etc.) fit in to the process, and how they should collaborate to create value for the customer and revenue for the company. Understanding each contribution and aligning them according to the common objective was a major challenge.

- Create flow: Everything should flow within every function or step of the value stream, and handoffs should happen like passing the baton between runners on a relay team. But flow in R&D is not easy to grasp because many steps are not very visible. At the time, Goodyear was like many companies in that we had tried to schedule every single activity using sophisticated project management techniques and software, and we managed the handoffs with ever-changing priority lists. With a fresh, first-hand look at the end-to-end value stream, it became easier to identify and eliminate waste (e.g., overprocessing), align to customer cadence, build in visibility where possible, apply some lean principles related to flow (e.g., concurrent work, single-piece flow, visual planning), stabilize the flow of projects, and gradually establish some process predictability.

- Implement pull: Where flow is not possible, the process should be designed to pull. Pull is effective in an environment of high variability, such as R&D, and we experimented with the best way to apply pull. We eventually chose a theory of constraints (TOC) pull method popularized by Eliyahu Goldratt and Jeff Cox in The Goal. We schedule only the bottleneck of our product development process (prototype manufacturing) based on customer demand and available capacity, and then align the upstream processes (e.g., marketing, engineering) with a TOC pull, and sync the downstream processes (e.g., testing, industrialization) with a FIFO (first-in, first-out) protocol.

- Work to perfection: When we reached the fifth step of the wheel, we wondered what else needed to be done. We had achieved improvements through the first four steps. We eventually realized that the fifth step is about having a process to continuously improve the way we were working. A3 thinking, as addressed by John Shook in Managing to Learn, became the way we embraced, discussed, and solved problems.

Goodyear began rolling with our improvement wheel in 2005, and we have been rolling with it ever since, deeply aligning our training with our continuous improvement process. The real value of the wheel is that it is continuous — we don’t get stuck forever perfecting our process. Instead, we complete a loop, sustain performance, and repeat the cycle, focusing on boosting the same performance objective or a new requirement.

Quality and safety at Goodyear have been industry-leading, so we instead turned the wheel initially to improve service (e.g., on-time delivery). We have since used it to repeatedly improve efficiency (e.g., speed, cycle time) and achieve other objectives that would have been hard to imagine in 2005. At that time, about half of our new projects met the business case for revenue and profits; today, nearly all projects meet the business case. In addition, our on-time delivery of projects to customers increased from less than 20 percent to 95 percent; product development cycle time was reduced by 75 percent; and R&D throughput increased by a factor of three. All this helped to grow operating income for Goodyear’s North American business unit to more than $2 billion.

Many readers will think: “This all seems like a manufacturing process — wasn’t this supposed to be an innovation creation process?” The answer is, “Lean principles are universal — they apply everywhere.”

Thanks to Jim, the wheel has been very good for Goodyear. Now if I can just get Jim to admit he has wheels after all.