While lean thinkers stress the importance of pull, and its attendant technology, kanban (cards or other indicators to facilitate smooth and level flow), most people find that practicing pull can be a real challenge. This is not something one person can do alone; there are no simple 5S checklists to help stage a mock exercise of this dynamic. Moreover, no customer ever asks for a product that is pulled to them; nor do reviewers note the degree to which their finished good has been (with the rare exception perhaps of barbecued pork) “pulled.”

Defining a Pull System

So what is pull and why does it matter? “Pull in simplest terms means that no one upstream should produce a good or service until the customer downstream asks for it,” write Jim Womack and Dan Jones in Lean Thinking, although they do note drily that “actually following this rule in practice is a bit more complicated.” (By the way, chapter four of this book is highly recommended for a detailed look at the practice of pull in the service of a complete lean enterprise.)

Essentially, a pull system links all production activity to real demand. Everything in the system happens only in response to actual orders from actual customers. This basic shift in thinking about making things represents a profound change in practices associated with a push approach, and was the key factor in Taichi Ohno’s statement that the Toyota Production System (TPS) broke completely from “conventional thinking.” No more batching of production; no more accumulation of inventory; and rather than isolated points of activity pursuing disembodied goals for abstract reasons, you have one complete system animated by a healthy tension aligning everyone around true value.

Essentially, a pull system links all production activity to real demand. Everything in the system happens only in response to actual orders from actual customers. This basic shift in thinking about making things represents a profound change in practices associated with a push approach, and was the key factor in Taichi Ohno’s statement that the Toyota Production System (TPS) broke completely from “conventional thinking.” No more batching of production; no more accumulation of inventory; and rather than isolated points of activity pursuing disembodied goals for abstract reasons, you have one complete system animated by a healthy tension aligning everyone around true value.

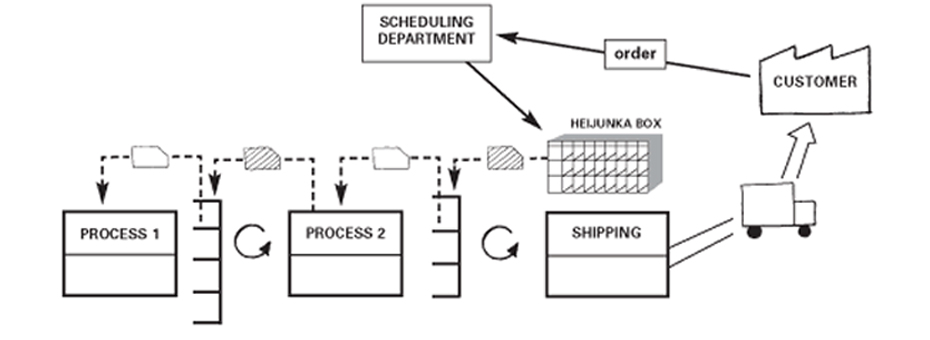

“Pull means providing the customer or following process with what is needed when it is needed in the right quantity, according to a ‘signal’ from the customer process,” according to Kaizen Express. Such an approach avoids overproduction and helps reduce the inventory in the process. Together with takt time and continuous flow, a pull system forms just-in-time. Note that kanban, which is a visual tool used to run a pull system, can sometimes be confused with the broader practice. But kanban specifically refers to a tool, the signaling device that provides authorization and instruction for the production of items in a pull system. Kanban fall into two categories: production kanban (indicating what to make) and withdrawal kanban (authorizing products or parts to move downstream).

There are many specific rules to pull including but not limited to: don’t send defective parts or products downstream. Only send something when it is asked for (not when you are done). Produce only the quantity that is withdrawn. Create smooth flow. Pull in the order in which it has been withdrawn. The discipline of rules such as this, all of which support quality and delivery goals, helps create a foundation for continued improvement.

More Than Just Reducing Inventory

The benefits of systematic practice extend beyond reduced inventory and less batching. Pull represents a binding spirit that fosters kaizen in all things small and large. It’s a prerequisite, a foundation, a system that triggers all the nifty tools and methods arising from the basic thinking approach of lean (and TPS). To say that all work must be “pulled” by the customer instantly imbues every action with meaning—it frames work and decisions as ways of delivering value to a specific customer and order rather than couching even a minor therblig as “something that has to be done.”

“Pull creates the tension that reveals problems, problems that must be seen, and dealt with, in a way that they won’t arise again,” Michael Ballé says in How Does Pull Relate to Problem-Solving? This dynamic causes a healthy tension that not only uncovers problems as they occur but demand immediate resolution so that the flow of work is not unnecessarily delayed. “What makes a pull system effective is not the pull itself, but the reactivity of people to problems when they appear,” he notes. “Learning can only occur when you have both the tension of pull, coupled with a firm focus on solving the problems that crop up. The old timers call this approach lowering the water in the river and seeing the rocks appear.”

Pull creates an architecture for kaizen, according to Balle, arguing that while you can do point kaizen successfully, in order to move to system kaizen (where you achieve radical improvement and sustain your gains) you must have an effective pull system in place.

This set of adaptive practices emerged in an improvisational manner, as opposed to being designed in a systematic manner. As shared in the chapter “Putting A Pull System into Place at Toyota” from the wonderful book The Birth of Lean, the adoption of the pull system principle emerged in a small part of a Toyota machining shop that had been operating in accordance with monthly production plans in the latter half of the 1950s. Faced with quality problems, and large inventories of raw material at the front end which were used as buffers to cope with the uneven pace of output in processes, certain managers responded by taking small steps to implement “pull” rather than “push.” This was done, in essence, as a means of removing control from a centralized (and often abstract) “plan” and placing awareness and control in the actual work, in what today we might call “real time.”

Remember that pull (and kanban), like any key component of a lean system, are not just ways of working, but ways of thinking that are bound to a set of other practices, and they draw their power from their evolution as the shared learning of many people over time. As noted in the Pull chapter, “Historically, the Toyota Production System is anything but a framework of physical tools, such as Kanban, and procedures based on a preexisting conceptual format. Rather, it is the shared experience and responses of the people who have participated in creating the program.”

What’s fascinating about the notion of pull are the wide-ranging applications. Jim Benson has developed a great body of work on “personal kanban,” a shrewd application of pull to personal productivity. Or consider, for example, this organizational implication: in Managing to Learn, John Shook describes a lean enterprise as one where a shared A3 thinking approach to solving problems, gaining agreement, and in fact developing others creates organizational “Pull-based authority” where each person at each level has clear responsibility and ownership, and uses A3 to get authority situationally: “Authority is pulled to where it is needed when it is needed: on-demand, just-in-time pull-based authority.”

And go even bigger: in his column The Wonder of Level Pull, Womack says that a robust pull system replaces the use of centralized information through an MRP system with one that is “reflexive”—akin to the nervous system in the body responding directly without needing to travel to the brain for instructions. This idea resonates with the Pull chapter of Lean Thinking, where Womack and Jones posit pull writ large as no less than a potential countermeasure to global markets characterized by chaos. They argue that most economic volatility is in fact “self-induced,” the “inevitable consequence of the long lead times and large inventories in the traditional world of batch-and-queue overlaid with relatively flat demand and promotional activities—like specials on auto service—which producers employ in response.” Macro-pull might, in their view, would greatly reduce lead times and inventory, which would not just stabilize demand in the economy, but in turn eliminate the traditional business cycle. Of course this might take as long as it does for an ideal lean enterprise to achieve perfection, but the general direction is the key.

For further reading: Creating Level Pull by Art Smalley