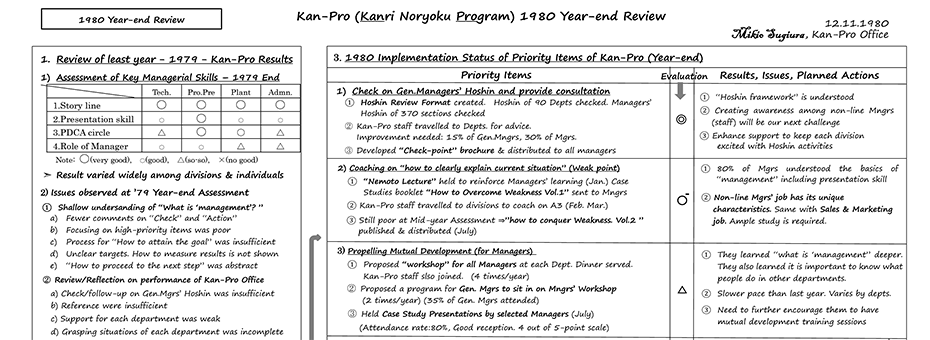

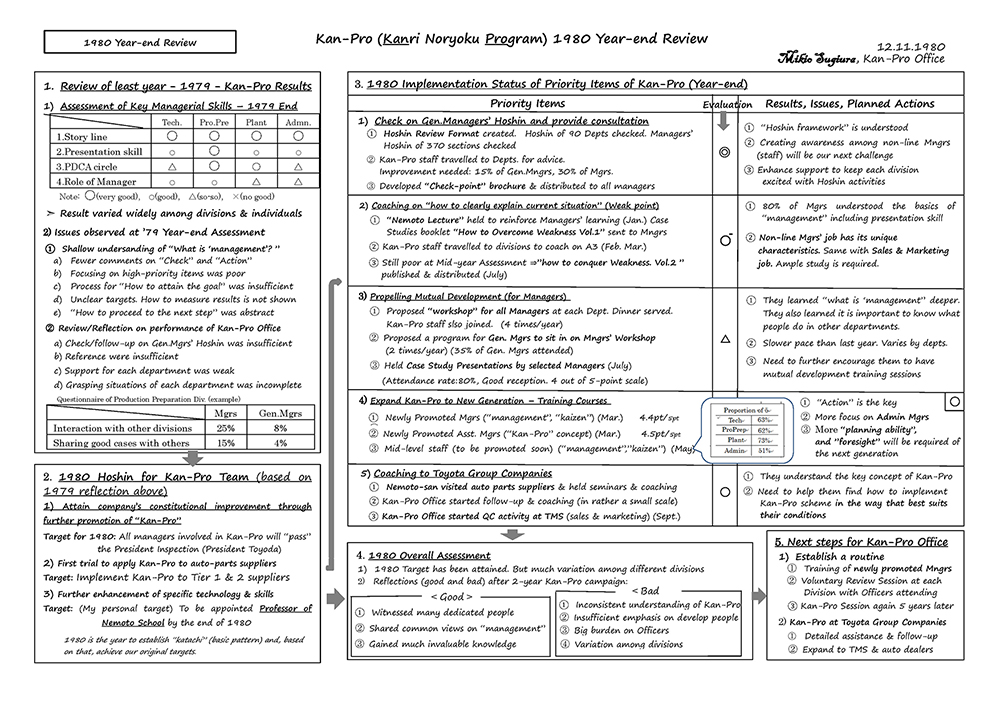

As promised yesterday, Yoshino has uncovered some important artifacts, including the A3 crafted by Kan-Pro architect Mikio Sugiura when he was reflecting on the results of the landmark initiative. With the launch of Katie Anderson’s new book Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn: Lessons from Isao Yoshino, now is a good time to dive more deeply into the topic of A3 and, more specifically, into the training program called “Kan-Pro”.

Today we will explore that A3 capturing the summary and reflections of Mr. Sugiura as well as some of our own reflections exactly 40 years later.

For easy reference, we’ll share the A3 below.

Click on the above image to enlarge it.

Note that this A3 is the year-end Hoshin A3 for Kan-Pro, the major activity for the year of the group Mr. Sugiura was managing, a unique department in Toyota called the “Corporate Planning Office.” This group was roughly analogous in the knowledge (office) work environment to the more famous OMC (Operations Management Consulting – responsible for advancing TPS throughout the company’s extended manufacturing organization, including suppliers) office within the company’s critical Production Control Department.

While the 1970s were an incredibly successful decade for Toyota, in hindsight it is clear to us that management struggled mightily to keep up with the breakneck growth that the company was experiencing. Many of the operating systems we are familiar with today were either born or became mature during this period. As managers struggled merely to keep their heads above water, senior management led by Eiji Toyoda noticed a decline in enthusiasm for the TQC processes that were established in the 1960s and worried especially that, with the growth in number of employees, managers were not adequately tending to the nurturing of the younger generation. Mr. Nemoto, who had led the 1960s TQM initiative, assigned Mr. Sugiura to do something about it. Kan-Pro was the result.

We’d like to highlight a few points contained in the A3:

- Mr. Sugiura’s personal hoshin is embedded as the target to become a “Professor of the Nemoto School”. There was no formal Nemoto School. But this statement of such an objective would be understood by all to mean that Mr. Sugiura was making a commitment to personal learning.

- It is highly unusual for such a personal statement to be included in a manager’s formal hoshin for his team (in Toyota at this time, hoshin would cascade in this formal way from the President /CEO to vice presidents to department heads as the “Department General Manager Hoshin (aka Bucho Hoshin). We figure that’s because he wanted to emphasize that this was a matter of personal development for which we should each take personal responsibility.

- The mid-term and year-end A3s are mainly fact-based or “scientific” but also highly personal, reflecting a “humanist” slant, as well. We are all human and each prone to our own: 1) biases (often hidden), 2) inclinations (better to make them explicit as appropriate) and 3) points of view (we each see only a slice of the elephant or the gemba pie).

- Remember that A3 (whether formal hoshin such as these or more day-to-day problem-solving or kaizen focused) are written down but are meant to be presented. The presenter thus tailors the presentation to the needs of the audience. When presenting these A3s to his team, Mr. Sugiura would emphasize and embellish certain points; when reporting to senior management he would flesh out others. Likewise when requesting support from parallel silos that coexisted alongside his department in the functional organization.

- Isao remembers Mr. Sugiura creating and sharing the A3. First, Mr. Sugiura created a rough “skeleton” of the story he wanted to tell. This is a common first step in the process for the A3 owner to clear away preconceived notions and consider the matter deeply. Then he gathered Isao and the other team members to a room where they all contributed to its creation.

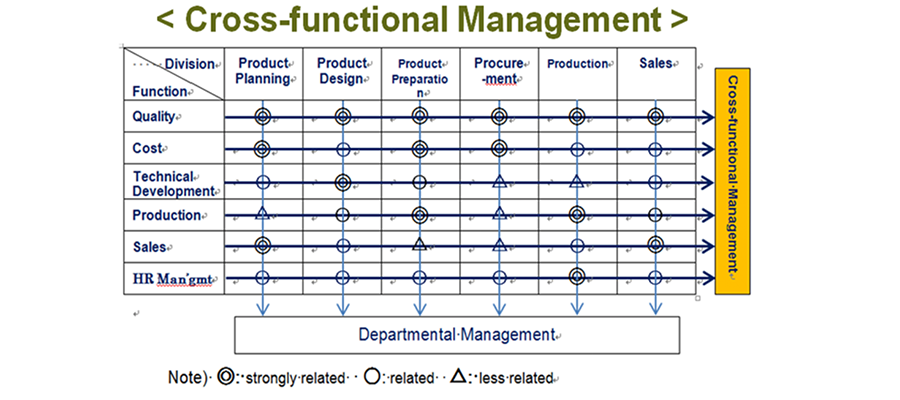

- By the early 1960s, Toyota’s organization was fully functionally organized (informed by studying copies of GM’s organizational chart they had received in the 1950s), with the dangers that such a matrix structure entails. In response, Eiji Toyoda sponsored Mr. Nemoto to initiate activities to ensure teamwork across the organization, including TQC and other management initiatives. Mr. Sugiura was a key member of Nemoto’s team at that time, establishing a direct link between Toyota’s TQC (famously leading to the company winning the Deming Prize) of the 1960s to Kan-Pro.

- A primary purpose of Kan-Pro was to promote the abilities and mindset of managers to work together effectively cross-functionally, which was seen by senior management as a concern in the late 1970s.

- As you can see in the A3, the overall assessment of the program was that managers were generally doing a good job of grasping situations, framing problems, and creating annual plans (hoshin planning). But, weaknesses remained (for example, in mid-plan reviews).

- At the conclusion of the two-year program, Toyota’s corporate-wide “Hoshin Kanri” process of annual planning, management, and review was firmly established. A3 management training for managers continued, not as the special Kan-Pro program but in the form of a set of formal courses provided for all Toyota managerial staff as part of their mid-career development and as pre-promotion training before becoming “kakaricho” (small group manager or assistant manager), in addition to post-promotion training at all levels of management.

- In our post of August 2, 2016, we mistakenly stated that that program was for managers of knowledge work only. Actually, the program included managers of all types of work, including production managers. While, as we noted in 2016, gemba is the first classroom for PDCA, the A3 process can provide a learning environment of a different kind, where reflection and careful analysis and deep reflection are possible and even required. Such analytical and thinking skills are critically important for improving work but also managing and developing people no matter the type of work being performed. Whether engineer, production manager, or knowledge worker, managing humans entails many of the same challenges and needs of the individuals involved.

One of the hallmarks of a successfully executed A3 process is that it is a collaborative activity (“it takes 2 to A3”), a learning process for everyone involved. For learner and teacher, senpai and kohai, sensei and deshi. The A3 paper is simply a convenience, a job aid to facilitate structured discovery. In this case, too, the 1000 trainees learned, but so did Mr. Sugiura, Isao, and the company.

The company learned, as acknowledged openly by the senior managers.

- Every manager who was involved in this program over the two years came to clearly understand their roles and responsibilities.

- The managers gained deeper understanding of the importance of the Hoshin Kanri System.

- Even before Kan-Pro, people at Toyota didn’t hesitate to report bad news. Kan-Pro further reinforced this tradition because of the focus on factual identification of problems and the level of praise toward managers and others who were honest about their mistakes.

- Through Kan-Pro, the level of the awareness of the role and importance of other divisions, including administrative roles, was enhanced, strengthening teamwork and the overall management foundations of the company.

- Everybody became familiar with using A3 process when documented communication was needed. People learned how to distinguish what is important from what is not. A3 thinking eventually became an essential part of Toyota’s culture.

Isao himself learned tremendously through reading and analyzing 1000 A3s. As Isao noted in our 2016 Lean Post, “Strikingly, I discovered that managers whose A3s were excellent were also excellent managers at work.” Through Kan-Pro, the A3 process was more than a mere mechanical problem analysis tool –it evolved to become a fully socio-technical process.

John experienced this directly five years later, not only from direct coaching from Isao and others, but from taking the exact managerial training courses that incorporated learnings from Kan-Pro and referenced in Mr. Sugiura’s A3. And over the succeeding decades, countless individuals in thousands of companies have learned from the process as well.

The overall program was never repeated, but key aspects of it were incorporated into the company’s manager training programs, and annual corporate-wide hoshin planning kanri process.

As we concluded in our posts of 2016, it is important to remember that what is important is the development of people, not specific artifacts such as training programs or A3 processes. It is critical to address critical questions. Are all the members of our organizations being given the opportunity to develop to the fullest of their potential? Are capabilities needed for the organization to survive and thrive being developed? In short, we want to constantly confirm and address the ever-changing managerial needs of our enterprises.

We think any organization is well advised to periodically assess and take measures to actively develop its managers. Kan-Pro represents Toyota’s effort in this regard as its go-go decade of the 1970s came to a close. With the turbulence impacting your organization today, how are your managers faring? Are they equipped as they need to be? How about considering something similar to Kan-Pro in your organization today?

Isao Yoshino, Okazaki Japan

John Shook, Ann Arbor Michigan

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.