Data is a critical component of value-stream mapping. But it’s not the only component you should be concerned about. All too often we find mappers getting caught up in their efforts to gather data, which can lead to overload and inaccurate mapping. LEI faculty member Judy Worth has seen this many times – I recently sat down with her to get her perspectives:

Where does this problem come from?

I think we’re living in a culture right now that says you have to have data – lots of it – to make an informed decision. Bill Gates said if you have the measurement right, you can change the world. And now we’re just drowning in data. The question is, what’s meaningful data, and what quality and amount do we need in order to improve?

Why exactly are we seeing such a big problem with this?

Part of it comes from IT, which has given us the ability to collect and analyze large amounts of data. We also live in a world where people are asking for transparency and the ability to show impact, or lack of it.

And you see this everywhere – in manufacturing, in healthcare, in office and service work, you name it. Everybody everywhere is looking to the data for answers.

What are the consequences of someone getting lost in the data?

There are quite a few. For one it can send you off in the wrong direction because you haven’t identified the key data yet – you’ve just gathered a lot of data. And another is data paralysis – people just feel like they can’t move forward without first gathering all the data there is.

Can you describe a time where you helped somebody deal with this problem?

Sure. Most recently I met someone at the 2016 Lean Transformation Summit out in Vegas who wanted my take on this. He was from a manufacturing plant and he said that his plant had been gathering data for a value-stream map for over one year and in that time they hadn’t begun any improvement work. He was really frustrated with the VSM process because he was under the impression that you couldn’t start without collecting all the data there was to collect.

So I shared with him that many of us out in the field have the experience of being able to use data estimates provided by good, experienced, frontline people who touch the work as a starting point, then start mapping and get the really hard, clean right data later. The key is recognizing that you need a baseline for improvement, but you don’t have to have that high quality of data to be able to figure out what the problems are, where they’re located, and which ones are the major heartburn and which ones are just little discomforts. You want only those metrics will help you deliver the customer’s needs and the business’s needs.

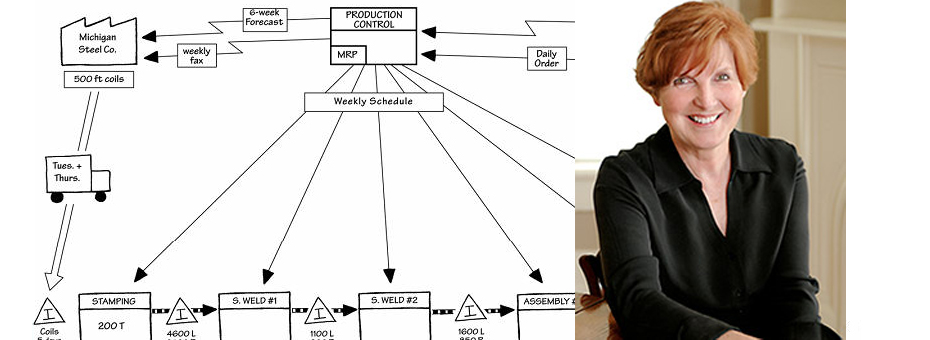

What would a VSM produced with an overload of data look like alongside one with a more focused approach to the data?

I don’t know that the maps themselves would look especially different, but here’s the thing – very often when we look at data estimates we look at ranges, so that we try to cover what happens 80 percent of the time, low-end/high-end range for things like process time. Then we start to look at why that range exists. In contrast, somebody who’s overly focused on data often wants to include a single “correct” data point based on a huge collection of data, which can cause them to overlook some important information about where problems are occurring.

What advice would you offer for ensuring that one doesn’t get lost in the data-gathering when planning for a VSM?

I always remind people that not all data is equally important to tell the story of the value stream. Having perfect data before starting the mapping is not critical. Having good quality data once the mapping is under way is critical because you need to show whether the changes you’re making are having an impact. I would ask someone about to start a VSM, “What story are you trying to tell and what data would you need to at least have a good enough estimate of to tell the story?” If you narrow their focus they’ll be on their way.