Lean practice thrives at the convergence of principle and practice. Many long-time veterans attribute their success to framing lean as a powerful improvement approach practiced mindfully by individuals with an eye towards both the immediate benefits, as well as the underlying thinking, which converts this from a one-time “fix” to an opportunity for learning. Seen this way, tools are both methods and principles; success rests on a thin edge of balancing technical and personal/social. To quote from Yeats, “How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

Perhaps (with an emphasis on the word perhaps) no tool captures this dynamic as vividly as 5S. “The key transformation lesson I’ve had to learn the hard way from my senseis is that lean transformation is about using the lean tools to develop the kaizen mindset in every employee, as opposed to applying the lean tools to every process to get a quick boost,” says Michael Ballé in 5S Again and Again and Again.

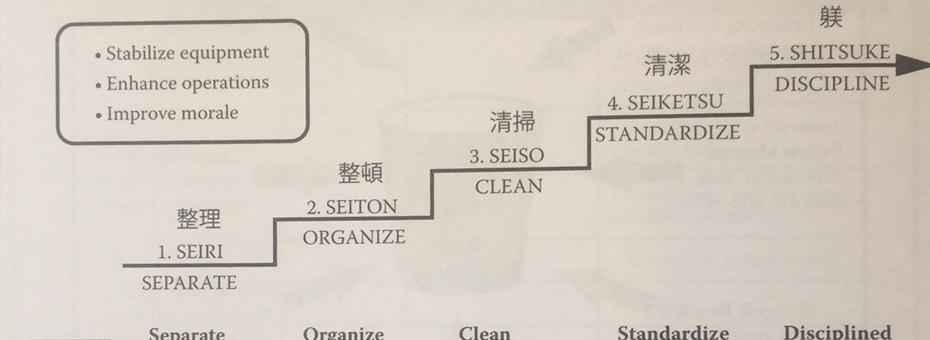

5S is a foundation of kaizen, according to pioneering thinker Masaaki Imai in his book Gemba Kaizen. It has become one of the best-known “tools” deployed by those looking to help others gain traction with lean and 5S is a perennial topic of interest to lean practitioners. Imai describes the five categories of this “deceptively simple system” as follows:

- Seiri, or “Sort out,” means to separate needed from unneeded things and discard the unneeded.

- Seiton, or “Set in order,”is to arrange items that are needed in a neat and easy-to-use manner and sequence of use or consumption.

- Seiso, or “Shine (and inspect),” means not only sweeping up the work area or cleaning equipment, but keeping the area clean and inspecting anything abnormal in the work area.

- Seiketsu, or “Spic-and-span,” refers to the overall cleanliness and order that result from disciplined practice of the first three Ss. It also means “Don’t litter the work area!”

- Shitsuke, or “Sustain”, is all about sustaining the first four Ss, and is sometimes referred to as discipline, or self-discipline.

Imai presents these steps as a sequence of activities that start with sorting, straightening, and scrubbing; and end with deeper systemic practices of systematizing so as to ultimately standardize the way that improvements will be undertaken. While the categories might be seen as isolated pockets of activity, each in its own way recapitulates essential lean disciplines. Seiso can be viewed as a proxy for TPM; there’s a clear link between Seiketsu and kata. And thinkers such as Imai and Pascal Dennis (in his Lean Production Simplified) present ongoing 5S as a core practice in creating basic stability.

Imai refers to the fifth stage as “self-discipline” as a shared mindset enabled by careful practice of the first set of activites. “Shitsuke means self-discipline,” he writes. People who practice seiri, seiton, seiso, and seiketsu continuously—people who have acquired the habit of making these activities part of their daily work—acquire self-discipline.” And that is why he can make the simple argument that, “5S may be called a philosophy, a way of life in our daily work.”

In other words, the true purpose of 5S goes deeper than a one-time housecleaning. Practicing 5S is a way to: create standards that reveal problems, support the basic stability needed to sustain incremental gains, reduce waste in all forms, build a disciplined workplace where teams focus on value-creating work, and nurture the essential sense of shared purpose needed to continuous improve to take root. An elegant way of describing this can be found in Gwendolyn Galsworth’s Visual Workplace, Visual Thinking: “The 5S system is designed to create a visual workplace, that is, a work environment that is self-explaining, self-ordering, and self-improving.”

Beware: Many stress the hazards of misguided 5S “programs” that merely add bureaucratic rules that prevent new learning and disable true initiative. “5S really is a method to teach people to take ownership of their own work environment so that they can perfect their standardized work by placing things at their most convenient place. Instead, in most companies I visit, 5S has become a bureaucratic program to make the workplace look neat, with no consideration for waste all over, and a fixation on “discipline.’” Ballé adds in How Can I Keep Our Lean Management Effort From Becoming Bureaucratic.

Run, then from any initiative teeing this up as a one-shot event rather than an ongoing practice of mindful work. 5S is a way of thinking, a discipline for improvement, and not a check-the-boxes exercise (an argument also made about the best use of A3 Thinking.) “The 5S program is about teaching management to engage the frontline teams in owning their workspace, and then their working practices’” writes Michael Ballé, “the purpose is to deepen the relationship of the teams with their own work and to teach managers to support them in doing so.”

The power of this approach resonates beyond that which we call lean: the notion of removing clutter and preserving only that which is useful, valuable, or simply brings joy resonates far beyond a TPS-setting. Dan Markovitz, for example, cited a great Anthony Bourdain piece of writing (and his post has a wealth of links) that shows how a chef’s mise-en-place (his “precisely and carefully laid-out system” of arranging his supplies and tools) represents “your physical workspace and your information precisely laid out so that you can find anything with your eyes closed. It’s the clean well-ordered inside of your head so that you can stay on top of all the work your boss, colleagues, and customers are dumping on you.”

This form of mental discipline overlaps with the most popular personal organizing system of the past few years; I’ve argued that the primary appeal of Marie Kondo’s wildly successful The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up is no more than a core lean attitude.

“Lean is about creating value by removing waste and all its attendant cousins (cost, time, distraction) in order to focus completely on what is needed. Likewise in the home, Kondo teaches how to remove every single thing that does not bring joy so as to live a simpler and more purposeful life: “When your room is clean and uncluttered, you have no choice but to examine your inner state. You can see any issues you have been avoiding and are forced to deal with them.’”

Finally, 5S has been widely embraced by broader communities to “revitalize and bring joy to the community.” In a terrific series about 5S in Japan (here, here, and here), Katie Anderson shares a wealth of detail about Ashikaga, the Japanese city which has rallied around the concepts of 5S (with over 200 organizations practicing daily). See how everything from schools to factories to a local winery are practicing 5S to achieve some noble purposes.

If you are getting started with 5S, I would suggest delving into the following resources:

- 5S for Operators: 5 Pillars of the Visual Workplace (and its mothership, 5 Pillars of the Visual Workplace: The Sourcebook for 5S Implementation by Hiroyuki Hirano). These terrific resources are as useful as they are earnest. Helpful guides to understanding the precise practices and reasons for 5S; the larger guide has a wealth of examples.

- Gemba Kaizen: A Commonsense Approach to a Continuous Improvement Strategy by Masaaki Imai. An essential resource sharing the system of kaizen. His chapter on 5S is pithy yet densely packed with wisdom about why exactly this approach provides real traction on the improvement path.

- Visual Workplace, Visual Thinking by Gwendolyn Galsworthy. A classic, visual-rich, resource with a rich context and insights.

Parabéns pelo trabalho. Muito bom.

Congratulations on the work. Very good