Lean is often associated with process improvement, error reduction, and greater efficiency in a wide range of numbers; yet most veterans argue that above all else, this system is primarily about healthy, productive, and sustainable coaching.

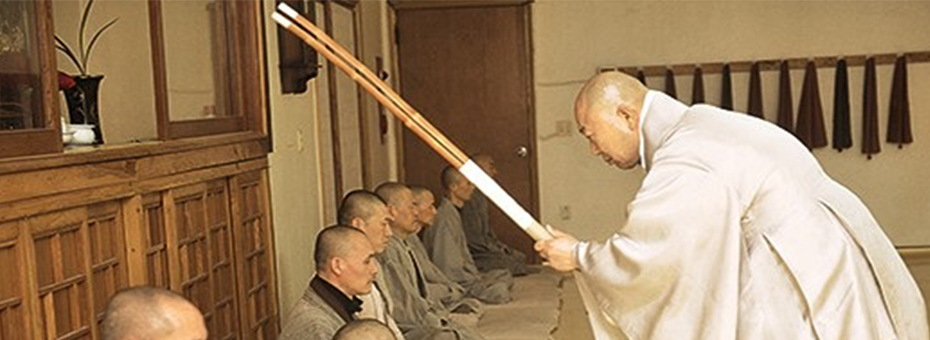

This work is more decidedly not all smiley faces and handfuls of M&Ms. In fact, the lean coach might show up in a seemingly brusque confrontation, says Dan Prock in Striking With the Zen Stick. Citing the use of a slat of wood called a keisaku in zen meditation to waken students from relative sleepiness, he compares the surprising whack from a sensei to the work of Taichi Ohno, who urged factory managers to see waste and conduct kaizen on the shop floor right away. Those in the West might call this a form of “tough love.” Prock presents the action as striking that person “with the Zen stick of reality and awakening him to the urgency to do kaizen.”

This sudden action serves as a respectful wake-up call, he explains, and highlights the role of the coach as a tough guide, working to build collaboration, reinforce a disciplined awareness of the immediate work, and ultimately cultivate a more “conscious bandwidth to be fully present.”

Effective lean coaches combine the social aspects with the technical, as seen in Coaching Effectively Within Takt Time by Jeff Smith: “A leader leads by doing, not just saying something. And when a leader does need to say something (about the Work), he finds several ways to communicate a message so the receiver can make it his or her own via application.”

A leader leads by doing, not just saying something. And when a leader does need to say something (about the Work), he finds several ways to communicate a message so the receiver can make it his or her own via application.

Moreover, he shows how good lean coaches teach within Takt Time, which he calls a “core operating principle to avoid the high costs of overproduction and its associated wastes.” Smith shares the work of Rick, a front-line team leader at NUMI back in 1993, who helped his workers grapple with getting their essential work done within a 90 second window of time. A conventional coach might at the least just tell the worker what to do; a coach lightly touched by lean might review the Standardized Work sheets developed for the job.

And yet Rick closely observed Vince, who was falling behind with a task, and helped him identify the source of the recurring delay (trouble loading and securing gas tanks into a truck frame.) By helping Vince see how his physical motions were creating extra work, understanding how to do this work more effectively—and then literally working on several repetitions of a new approach together—Vince came to adopt a new and better approach.

This hands-on, collaborative improvement dynamic animates the lean coaching approach. As noted by Jim Womack in It Takes 2 (Or More) To A3, genuine learning and improvement occurs only when both teacher and student are deeply immersed in a detailed exploration of the specific problem at hand; with the coach serving as a humble guide shaping the discourse:

“The real magic here is that the owner takes responsibility for addressing the problem through intense dialogue with individuals in areas of the business where he or she has no authority. During the A3 process, the owner actually manufactures the authority for putting the countermeasure in place. However, this type of authority is not a matter of control delineated on an organization chart. People in different areas with different bosses energetically participate in implementing the countermeasure because they have actively participated in the dialogue that developed what they believe is the best countermeasure for an important problem.”

Indeed the more powerful and effective coaches may in the long run be those who best learn to avoid control and excessive instruction; and instead are clear in their language and respectful of other’s learning. In One Simple Thing You Can Do to Improve Your Coaching by Tracey Richardson probes this delicate relationship:

“The language we use and approach we take largely determines the quality of conversation we have. Empowering people to do things they don’t believe they are capable of is a gift, one I received through the shared wisdom of my Japanese trainers at Toyota. A good coach should play the role of a servant leader. The leader works “for” the learner/coachee, removing barriers and constraints, helping them improve their work. Every coaching experience is an opportunity to figure out the best approach to communication; it depends upon the personality of the “learner”.”

She stresses that leaders who ask questions that make people defensive shut down productive work and create robots who simply go through the motions, noting, “A workforce without the power to think is like having a vehicle without an engine, it isn’t going anywhere.”

Of course the habits of such humble coaching are never easy to develop. For Josh Howell, the path to healthy coaching meant Hanging Up My Cape and learning to stop considering himself a superhero dropping into fix problems on the front line—a “legend in my own mind.” The path to becoming a problem seeking and coach who patiently observes the work and respects the worker is both personally daunting, and when travelled, productive for all.

Another key aspect of lean coaching: never underestimate the value of pushing people to realize dramatic gains quickly (and of course helping them achieve these improvements.) As Art Byrne states in Ask Art: Am I Showing Respect for People by Asking for Fast Action?, “setting stretch goals to me shows tremendous respect for your people.” He considers this an integral part of a learning culture where ambitious gains are expected—and where every individual receives the coaching and support needed to continuously improve.

Finally, Lisa Yerian preaches the value of trust and respect that runs through the improvement work at the Cleveland Clinic, where she serves as medical director of continuous improvement. She counsels that you Stop Asking Your Leaders to “Support” Your Lean Transformation: instead of framing the work with such a “soft” and potentially misunderstood quality, aim to make very clear, specific asks for any collaborative improvement. This fosters a greater emphasis on digging deep into the situational details, helps establish how each player will engage, and pressures the coach into familiarizing themselves with the real work at hand.

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.