You learn through solving problems, failing, reflecting on failure, and adjusting course.

That quote sounds like something from Deming or Toyota. But, no, that’s from that erstwhile problem solver née inventor Steve Jobs.

There may be nothing more fundamental to lean thinking and practice than problem solving. For that matter, there may be nothing more fundamental to being human than problem solving. We breathe, we eat, we create civilizations – we deal with (solve, tackle) problems every step of the way. The lean transformation framework that we at LEI and LGN (Lean Global Network) have been using to frame the challenges of changing ourselves and our organizations in desired directions begins by asking the same question that Toyota begins with: what problem are we trying to solve?

But, to label an activity “problem solving” neither solves any problems nor explains what problem solving even means. It may in fact create some. What is problem solving and how can we do it more effectively? The answer to how we can do it better is “it depends.” But, depends on what?

That’s where Art Smalley’s new book Four Types of Problems comes in with a powerful contribution. Born of Toyota’s problem solving approaches and philosophies, Art’s framework gives us a practical yet profound way to move forward. Let’s consider how it is helpful and ponder how you might use it.

Not every problem looks like this familiar lean classic from Taiichi Ohno in which the problem of a machine breakdown can be tackled via a straightforward root cause analysis:

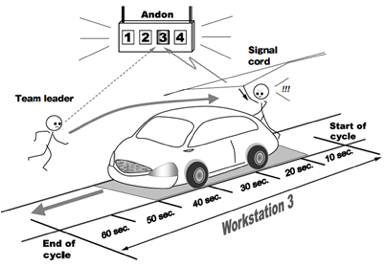

Sometimes problems are coming at you way too fast to pull out an A3 sized sheet of paper or sit down for a thorough five why causal analysis. Think about a sudden accident and a trip to the ER. Or when your house is on fire. Or when a serious work condition requires attention. Sometimes you need to respond NOW:

Effective Type One problem solving is much more than merely applying “bandaids”. Toyota’s Jidoka concept informs countless examples of highly structured and effective processes that enable extraordinary levels of operational stability, providing a robust foundation for Type Two root cause analysis when called for.

This illustration explains (to view, click here and come back in seven minutes!) Toyota’s famous “stop-the-line” andon system (technically, the “fixed-position stop system”), which embodies a meticulously designed process to enable effective Type One problem solving. To enable flow yet contain any problem or defect, the process engages each worker in identifying and responding to each problem as it occurs; yet despite hundred and even thousands of andon calls each day – with each problem responded to one by one – overall flow is interrupted only a few minutes per shift! Powerful, indeed.

Effectively tackling these types of problems may nor may not require a casual analysis later. If you don’t have these skills at responding to things gone wrong, good luck with your kaizen. As Jim Lancaster reminds us in his book The Work of Management:

“If Lean improvements are not impacting your income statement and you have little time for improvement work, maybe you don’t have an improvement problem, maybe you have a deterioration problem.”

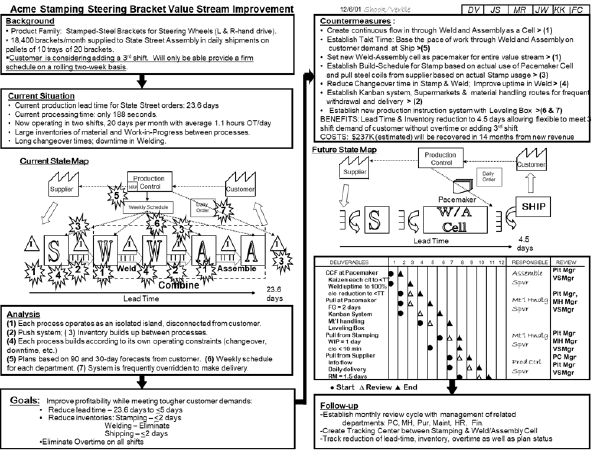

And, not only that, you don’t really want to sit and wait for problems to come at you. You’d like to move from reactive to proactive mode, develop a target condition and take action to learn your way to get there. This is what Acme Stamping did in the classic example from Learning To See; After a quick mapping exercise revealed the fact that material was moving at a snail’s pace that required about one month to slog through Acme’s operations, yet the actual value creating work time was only about three minutes (ouch), Acme decided to blow up its production process, beginning with a radical transformation of the flows of material and information which necessitated changes in…everything. Spending essentially no money (creativity before capital!), Acme figured out how to reduce lead time from a month to less than a week:

As for Type Four problem solving, think of deciding in 1960 to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade when the path to achieve this loftiest of lofty ambitions was fraught with uncertainty, known and unknown unknowns, and tremendous risk. JFK indeed carried an expansive view of problem solving; consider these words he delivered at American University in 1963 “No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings.”

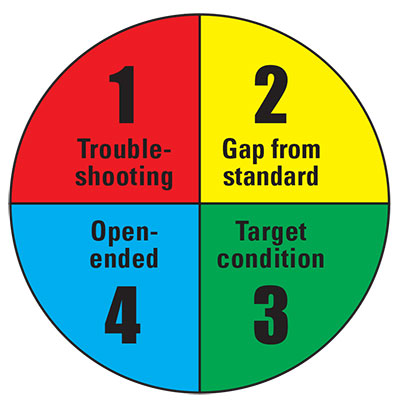

in these four approaches enables an organization to attain stability, sustain gains, and advance steadily towards its goals and visions. The four types in summary:

- Troubleshooting: a reactive process of rapidly (and sometimes temporarily) fixing problems by quickly returning conditions to immediately known standards or normal conditions.

- Gap-from-standard problem solving: solving problems at root cause relative to existing standards or conditions.

- Target-state problem solving: removing obstacles toward achieving a well-defined vision or new and better standards or conditions (i.e., kaizen or continuous improvement).

- Open-ended problem solving & Innovation: open-ended pursuit of a (perhaps) vision or ideal conditions (new products, processes, services, or systems).

Graphically, you can think of it this way:

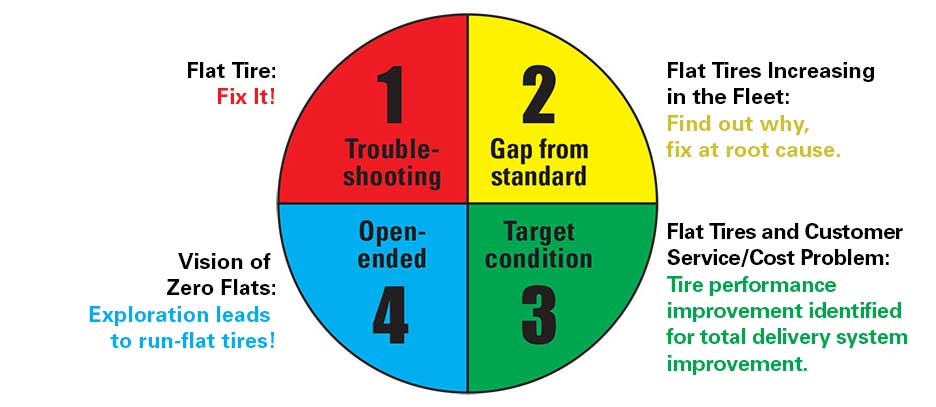

In other words, problematic situations can be viewed through different lenses and viewing angles. For example:

No one size fits all in building skills, in coaching others, or in problem solving. There are already way too many hammers running around looking for nails to beat down. The most important contribution of Art’s Four Types categorization is that it provides a self-reflection framework for managers and executives to assess and understand the state of their organization’s problem-solving capability. Does your team (do YOU?) have capability in all four types? Probably not. Surely no one is as strong as they’d like to be across the board. Your team may be very strong in the skills required to perform well in one or two of the types of problem situations and quite weak in the other two. Solid skills across the board will enable you and your team to flourish no matter the kinds of problems that present themselves to you.

With Four Types of Problems, Art Smalley is helping LEI and you in the lean community or anyone working within any team context to address the problems most critical to the long-term health of their organizations—the challenge of how to support the development of better problem-solving organizations and individuals. We know that Four Types of Problems does NOT represent the final word on this important topic. Rather it is the latest step forward in the evolution in a long history of humans trying to solve problems and make things better. As such, our hope is that Four Types will kick off a new round of exploration. And so this particular problem-solving process, for LEI, includes a feedback loop from end users for us to learn what works, what does not work, and how certain tools actually get applied. We look forward to learning how you actually use this book, and with that information we can understand if we have solved our problem.

John Shook