The secret sauce of lean is the development of people. One person after the other, one quality issue after the next. When a person develops their technical competence, they become more autonomous. People who have a greater sense of autonomy will become more confident in their own abilities. When we are more confident in our abilities, we are more willing to try new things, to look for opportunities for kaizen. Kaizen, in turn, develops our technical skills. A virtuous cycle of learning and people development, with business development as a result.

Flow is an outcome of the deliberate, technical, learning practices found in the lean learning systems. Flow is what you achieve when people have the skillset and deep knowledge of work required to “make one, sell one” at the rate of customer demand in the smoothest possible way.

Flow is described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi as “the moments when you are completely absorbed in a challenging but doable task.” Is it possible to create and re-create these moments? Absolutely. By puttingWithin this system, quality issues are understood above all as a source of learning, both in terms of product and process. And if we get too preoccupied with the flow of processes, we quickly find ourselves worrying only about delivery. ourselves in challenging situations where we excel but still find room for improvement. This, in its essence, is the insight of leans “respect for people.” To challenge and support people in developing technical and social competence through problem-solving and kaizen. Which gives us as an organization of people, better and better able to deliver customer value – and in turn, deliver a sustainable profit for the business to survive and thrive.

As Dan Jones and Jim Womack observe in their classic Lean Thinking, the first principle of lean is customer value. Lean starts with the customer because our aim is to 1) Connect customer value with capabilities, and 2) develop these capabilities by looking deeper into the technical solutions, the quality that creates customer value. What is it that the customer (or user, if you work with public services) really values about your product (physical or non-physical) and how do you deliver this value? The third goal of this work is to allow people to use their creativity to solve challenging and interesting puzzles together. Start by looking at the source of customer value and quality, and all else will follow.

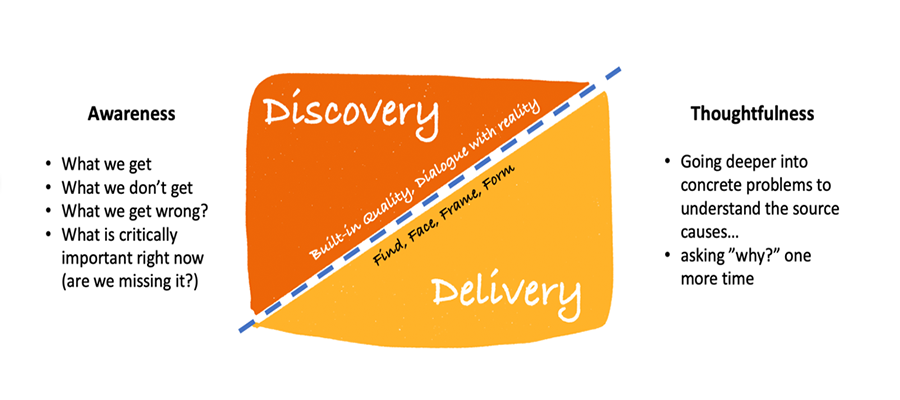

Within this system, quality issues are understood above all as a source of learning, both in terms of product and process. And if we get too preoccupied with the flow of processes, we quickly find ourselves worrying only about delivery. We default to quick fixes and frame all problems as solutions to be created rather than opportunities for learning. Where are we in the process, have you done this or that, what should you do next? Drop this and do that instead. This type of leadership behavior creates mura (unevenness), which, in turn, overburdens people (muri). The result is a lot of waste in our work (muda).

So how do we change this self-reinforcing system? We start with quality and engage everyone in problem-solving.

Flow in Operations

The full power of lean as a learning system can only be realized when leaders reframe how they conceive of and use the lean tools. They are not process-improvement tools that, when implemented, will immediately improve the flow of work. They are tools of discovery that show us the real problems we must face. When people are passionate about creating customer value, they use lean tools to find and solve problems. For example, to create the smoothest flow of work in operations, one must study the three parts of standardized work: 1) takt-time, 2) in-process stock (physical or non-physical), and 3) the basic flow of human motions.

The full power of lean as a learning system can only be realized when leaders reframe how they conceive of and use the lean tools.

These are learning tools, and there are no easy solutions to the questions they ask us. However, set aside time for discovery, dig deeper into the issues that are uncovered, and challenge your own understanding of what you are looking at, and you will uncover new knowledge for yourself, operators, engineers, and managers alike. What do we know, what don’t we know, what is important right now, and do we know? Are we willing to learn?

Flow in Product Development

Flow is the outcome of a deeper technical understanding of work. In product development, flow happens when a team of engineers immerses themselves in a technical issue that will make or break the new product, supported by visual management of the product, not the process. In the words of Alan Mulally, former CEO of Ford: “you can‘t manage a secret.”

The product Obeya is a key scaffolding to create the conditions for this immersion to happen. The Obeya is a tool that supports cross-functional problem-solving. It is not a tool that allows middle managers to tighten the grip on the process, come hell or high water. Flow is not process optimization. Flow is what happens when we have a deep understanding of our own work — what is quality, what is value, how do we know, how do we create it? Together.

Laerdal Medical is a global company that supports the healthcare industry with training equipment and programs. Their aim is to help improve patient outcomes and survival. One of the authors (Eivind) has worked with Laerdal over the last two years to support the cross-functional collaboration between production and product development.

Flow is the outcome of deeper technical understanding of work. In product development, flow happens when a team of engineers immerse themselves in a technical issue that will make or break the new product, supported by visual management of the product, not the process

Their most famous product is probably Resusci Annie (of “Annie, are you ok” fame). For Laerdal, a technical issue launched an ongoing learning journey meant to improve customer value, quality, and cost. To do .so, a cross-functional team, from product development and production, has committed to a takt-time of monthly gemba walks and Obeya meetings to discuss customer value, quality, and competence. Each gemba walk and Obeya meeting is an opportunity for discovery and to develop a deeper understanding of the customer: What do they really value?; the product: How well are we aligned with our customers?; and competence: Do we have the capability to develop and design a truly great product at the right price, and that is easy to assemble and loved by our customers? These are hard questions, but asking them and setting aside time to do so is what enables the smooth flow of delivery.

Flow in People Development

Toyota considers the basic flow of human motion as one of three parts in standardized work, along with takt-time and in-process stock. Every step, every moment, every movement counts when recreating the steps that deliver customer value over and over. Toyota’s insight is that knowing the steps is not enough to deliver customer value.

During a gemba visit to a small factory on the northwest coast of Norway, we observed how the factory had started to experiment with a different, more hands-on method for leadership development — inspired by the Training Within Industry programs of Job Instructions, Job Methods and Job Relations, and Toyota’s interpretation of these (described, among other places, in Toyota Talent by Jeffrey Liker and David Mayer). Part of a multinational corporation, the factory had access to a full range of leadership development programs. However, none addressed the realities of the gemba. What they are discovering was that no-one has really looked this deeply and thoroughly at the actual work before, and reflected on the skills and competencies needed to perform the work to the quality standards that deliver the value that customers actually want, at the price they are willing to pay. The experiment opened the door to a whole new level of improvement activities and inspired the line leaders at the factory to involve all employees in problem-finding and problem-solving.

Developing people by studying deeply the basis of standardized work

The aim of lean is to develop people who have a passion for making things (creating and building great products and services) and the skills to make them.

In another example, Volvo cars had worked with lean since early 1990 but wanted to take the next step. A few years back, they decided to set up a leadership development program that offered the participants an opportunity to study deeply and improve significantly one manufacturing process. They focused on a process of around 60 seconds, with numerous variables from customer options and model variants (each factory manufactures at least 3 to 4 basic models on the same production line). For each cohort, the participants from the global organization from different backgrounds are selected by upper management. They come from key positions in manufacturing, logistics, and engineering and are either part of upper management or close to it–in other words, critical managerial positions.

In the fiirst, a week of theory, the aim is to give the participants a systematic overview by looking at practical examples of the whole supply chain on the gemba. The “classroom” is a host plant that, ahead of the training program, will need to challenge themselves to show good examples of, among other things, standardized work, material supply, levelling, and so forth. They look examples of where they believe they should be, not for where they are; this puts pressure on the plant to make real improvements to show good examples.

Before the start of the second week, the students, as homework, will study a video of one cycle of work ahead of the real gemba training. When the group meets again for the second week of training in the host plant, they are tasked with studying one area and implementing improvements. The first three days, everyone deep dives into the 60-second cycle. They aim to resolve overburden (MURI) and instability (MURA) by themselves as much as possible. After three days, all the processes studied are put together to form a bigger picture. A target is set, and the students are then tasked with rebalancing and testing their ideas. Done during running production (24/7), this exercise forces them to use the small breaks to make changes and run their test model. On the last day, everyone has to finish their work to allow the host plant to run their now-improved process. At the end of the training program, the students are tasked with sharing how they will take this “once in a lifetime” experience of learning TPS by doing and apply their new competence as managers. To lead others, you need to be the change yourself.

Flow is personal; it’s being in a moment of enrichment, a mental state; it’s stretching oneself just that little bit extra, not because someone else tells us to, but because we love doing it. The aim of lean is to develop people who have a passion for making things (creating and building great products and services), and the skills to make them.

Investing in Work(ers) Using Job Methods and Job Instruction

Learn how to develop team members for sustained success.