No company can become lean unless they move from batch manufacturing or, in the case of service type companies, from functional specialties to flow. This is one of the most important principles when it comes to becoming lean. Functional specialties in, say, a hospital or insurance company create long lead times, excess processing, lots of waiting, excess staffing and unacceptable levels of quality. For manufacturers, we can add excess inventory and floor space to this list. Flow, on the other hand, exposes and eliminates these problems without the need for capital spending.

Let’s start with the batch approach, which is the most common method for traditional manufacturing companies—in fact just about all companies. Maybe it is just human nature that people believe batching is more efficient. I don’t really know. But this belief has been around for many decades. As manufacturing companies moved from early craft production to specialization, and then as things became more machine-based, to a system of one-man-one-machine; somewhere along the line we also decided that similar machines are happiest when they are placed next to other machines just like them. So, we grouped similar machines into functional departments: all punch presses together, all screw machines together all drilling machines together, etc. This was done to keep the machines happy and to try and get efficiencies by having one man say, run two machines. We did a similar thing in hospitals, where we created a large number of independent fiefdoms based on narrow specialties, such that a patient has to travel through 10-12 different fiefdoms to get treated.

Once these functional manufacturing departments are established the fun really begins. Products being made may have to travel through eight different functional departments. Simply figuring how these parts move through the various departments adds an enormous amount of unnecessary complication. People need to create routings and move tickets. You will also need labor tickets to keep track of the cost that is being added at each step. This requires sophisticated MRP (materials resource planning) systems to even have a chance of keeping track of everything.

With this approach the parts travel long distances from department to department to get made. Sometimes miles worth. They are small. They get very tired. We want to take good care of our parts so we build them a nice place to rest in-between their travels. This is the WIP inventory area or as I call it “The Parts Hotel”—nothing more that a bunch of sleeping money that is totally unnecessary.

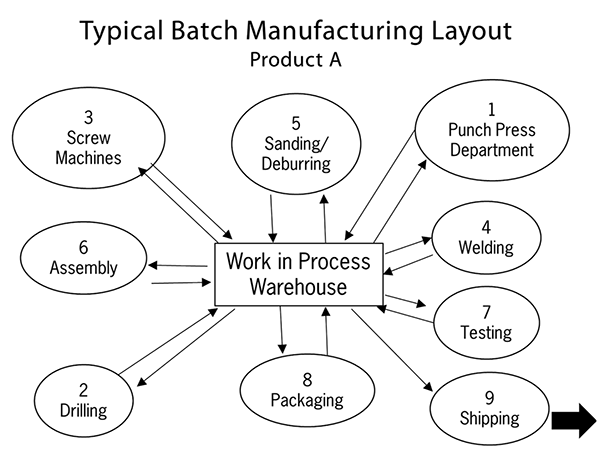

As you might expect, getting everything through this maze takes a lot of time. Lead times are in the 6 to 8-week range and are locked in by the MRP System that we paid a lot of money to install. The same thing happens in a bank where a loan application may take 3 weeks to get processed when the actual touch time labor is only seven minutes. A schematic of what this would look like is shown below.

This shows a process for product A that has to travel through eight different functional departments, with rest stops at the parts hotel, in order to get made. A pretty typical situation. But the fun is just beginning. The machines in each of the various departments, and sometimes within a given department, all run at different speeds. This means we need to adjust for this in our planning so that we won’t make too many bases and not enough covers, for example.

Everything goes through each department in batches. The batch size is determined by those clever boys in the finance department based on the length of time it takes to changeover the various machines. The changeover times are taken as a given, “not much we can do about that” and the batch sizes err on the side of being too big rather than too small.

You will find a similar situation in a life insurance company that takes 44-48 days to underwrite a new policy (i.e. give a quote) when the actual time for an underwriter to do the work once all the information that is needed is available is about 15 minutes on average. Think of the waste that exists here. This occurs as the work gets passed back and forth between the underwriters and the case managers just like the functional departments in manufacturing.

A primary focus of any company is to “make-the-month” so we skimp a bit on machine maintenance. The result is that machines break down all the time and always at the worst time. For service companies the computer system goes down. But the finance boys still want to make the absorption hours in order to “make-the-month”. So if one of the eight machines in this example is broken today, finance will insist on running the other seven to make the absorption hours even if we cannot make one single product today that we can sell to a customer. If the machine that makes bases is broken down we still will blast out covers and wind up with a big imbalance in parts. The inventory piles up. We have to move and store it and move it again. We lose it, we spend time looking for it. We damage it in the moving but hey, so what, we made the absorption hours and the month looks pretty good. We have plenty of inventory to cover up the problems and six weeks (the lead time) to get the broken machine fixed and catch up. What could go wrong?

And, oh yes, I forgot to mention the quality issues that this batch approach can cause. How, for example, do we fix the problem if we don’t find out we have that problem until six weeks later at final assembly? How can we answer any the following questions: What department caused the defect? What machine in that department was the defective part run on? Who was the operator, we work on two shifts? Whose raw material was it, we buy from three different vendors? Oh, and we have 6 weeks of defective parts in the system; what do we do with them? The same is true for the underwriting department, whenever the number of cases stretch beyond 48 days because they somehow got lost in the shuffle. Do we even bother to complete them? After all it is only a quote and our hit rate on quotes is well below 50%.

I think you get the picture. The waste that exists in this functional approach is enormous but we can’t see it. “But we’ve always done it this way.” But what about flow? What are the benefits and how would you do it?

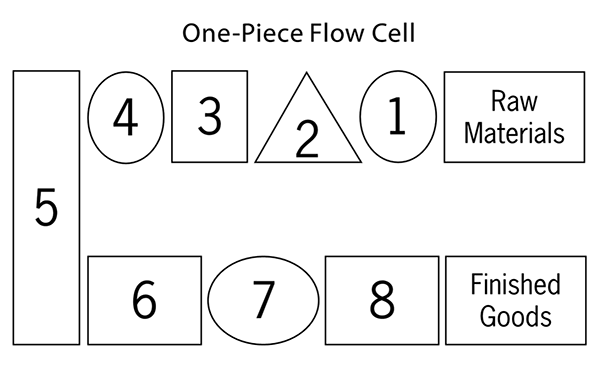

To switch to flow we start with understanding the takt time. What is the rate of customer demand that we have to meet? Let’s say it is 60 seconds required per product A in this case. Based on that we can observe the labor needed in each department to make the part. What we find is that it is very uneven. Almost every operator requires less than the determined takt time to do the work. We don’t see this in the batch state because the work is done in 8 functional departments. In fact, by lining up the machines in a one piece flow cell as shown below we discover that if we load each operator to takt time we can go from having 8 operators to 3 and get the same output.

Of course we have to move a number of machines, and the operators will have to learn to run more than one machine to do this. That is a bit of a challenge, but going from 8 to 3 operators gives us more than a 60% productivity gain, and significant quality gains as well. These come from the fact that now if there is a quality problem you see it right away, not 6 weeks later; and you know what machine, what operator and whose material caused the problem. This gives you a high likelihood of not only solving the problem but of getting a permanent solution. In fact, in my experience, moving to a one-piece-flow can very quickly result in a tenfold improvement in quality. And you never wind up with 6 weeks of bad inventory as you only have 8 pieces in process when you find the problem.

One-piece-flow also forces you to establish a preventative maintenance program. Now, when one machine goes down they all stop. You have an emergency, and so you have to fix the problem now. This may cause some problems early on but they will be solved both quickly and permanently. Also, having things in a one-piece-flow eliminates the need to push product through the system. Now you can pull it. You don’t need a complicated MRP system to schedule the shop floor anymore. Also you no longer need to build to a forecast, which most of the time is wrong anyway. The arrival of a simple kanban card will initiate the order for product A. Inventory goes down, travel distance is reduced, space is freed up, safety is much improved, quality is way better and you have a big productivity gain. Life is good or at least getting better.

But wait, I forgot to mention the biggest gain of all, the strategic benefit that results from moving to a one-piece-flow. Can you guess what that is? Well, in the batch state with functional departments and push scheduling you had a 6-week lead time from when you started till a finished product came out of the maze. Now, from the arrival of a kanban card and the start of production it takes only three minutes, 3 workers times one minute each, to go from raw material to in-the-box. This is a significant strategic win for you as you can now leverage this in the market place by offering a 1-2 day lead time while your competitors are still stuck at 6 weeks. You will gain market share, most of it at full book price, because of your shortened lead times. You will grow and be more profitable as you don’t need to give away your productivity gains if you can compete on speed.

So, in answer to your question, flow production takes something that is inherently very complicated, functional departments and batch production, and greatly simplifies it to your great advantage. So what are you waiting for? It’s clear that flow is the way to go!