There are many challenges for lean in government: the structure of the workforce, disincentives for risk-taking at all levels, complex stakeholder relationships, and the simple problem of challenging the status quo. Still, while it may be difficult to bring lean thinking to government, it’s not impossible. From our experience working on lean and lean-inspired change programs in the public sector, we’ve found that leaders in this space get easily discouraged. They shy away from lean not only due to the challenges above, but to a variety of perceived challenges we believe can be overcome with a different mindset.

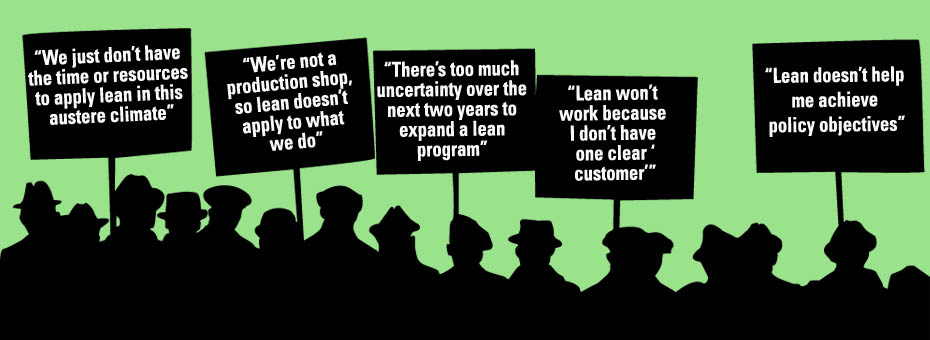

Here are the top five reasons we hear lean “can’t be done” in government with some ideas about how to think about them differently:

- “We just don’t have the time or resources to apply lean in this austere climate”

For most government agencies, the volume of work and expectations of citizens and other stakeholders have increased while the number of employees has stayed constant or decreased. Recent articles on backlogs at the Department of Veteran’s Affairs and Social Security Administration highlight this problem. Government workforces are under increasing strain to produce. Leaders worry about whether their people have the time to even get involved in lean while continuing to work through backlogs and manage other priorities.The case for lean? First, this situation is a perfect burning platform for improvement. While political winds and policy decisions may make it easier to find more capacity for improvement, waiting for an excess of capacity to do improvement work means improvement work will never begin. It’s better just to start. Second, many improvement activities provide quick relief to a beleaguered and overworked workforce. Daily team huddles and visual boards showing where backlogs exist and who’s responsible for tracking down issues can energize workers by providing them real agency and control over their work. They help managers support their teams more effectively by providing transparent, real-time information on progress. While these practices are only small parts of a lean management system, they don’t take much time to get started and they unlock more capacity for improvement work. Removing non-value added time from processes is THE essential work that helps government agencies handle this capacity crisis. Effective leaders recognize this and devote their precious time and resources to solving the right problems.

- “We’re not a production shop, so lean doesn’t apply to what we do”

The reality is, lean principles apply to any process, especially complex ones where waste is often hidden behind complex patchworks of rules and across widely distributed experts. These processes are made difficult and cumbersome in ways they don’t need to be. Common problems include: overly complicated instructions, an unclear view of who the customers are and what they need, and/or poor coordination across functional groups.The case for lean? First, get rid of the idea that lean offers cookie cutter solutions to complex problems; it doesn’t. It does, however, provide a set of principles and practices that will help leaders and teams discover where hidden waste resides, align diverse stakeholders on needed changes, and develop effective solutions that lead to consistently better outcomes. Value stream mapping, for instance, helps experts involved in a process that could take months or even years to better understand the needs and requirements of groups upstream and downstream of themselves and learn how work can be better coordinated to eliminate bottlenecks and rework. Developing standard work for important parts of the process, rather than being restrictive and controlling, free leaders up to focus on the decisions that only they can make. Atul Gawande captures this well in The Checklist Manifesto when he says “[Standard checklists for complex processes]… ensure people talk and coordinate and accept responsibility while nonetheless being left the power to manage the nuances and unpredictabilities the best they know how.”

While complex processes can never be scripted and experts will always need to exercise good judgment, smart leaders create the conditions that lead to better outcomes. Recent success stories of lean in healthcare and state and federal environmental regulation demonstrate the promise of using to lean to improve complex processes.

- “There’s too much uncertainty over the next two years to expand a lean program”

Time is of the essence for improvement efforts in many agencies since political winds and political appointees change regularly. While it will take any complex organization years, even decades, to truly transform their management systems, government leaders wanting to pursue lean can’t wait that long! They need to show tangible results in a short period of time and build excitement so their efforts can continue two more years… then two more years, etc.

The case for lean? Precisely because of this political dynamic, lean leadership is critical. New leaders will be aware of lean, have a positive view of its potential, and will ensure lean efforts continue under a new administration. Next, lean done right builds learning through action and inclusiveness. This bias for acting fast and including a lot of people means government leaders can quickly realize progress on small problems while also building a foundation for progress on tougher problems. Focused problem solving through kaizen events are a great way for leaders to get started, but they can’t stop there. As more people are exposed lean, even in small ways, they become more likely to influence new leaders to champion and sustain group efforts. Finally, lean management practices can be used to help leaders achieve a wide variety of policy or operational goals. Even when leaders and their goals change, the management practices themselves are durable. Those are likely to last in some form. Leaders who are serious about making a difference can use lean thinking to make sure their hard work and vision continues when they’re gone.

- “Lean won’t work because I don’t have one clear ‘customer’”

Government leaders are right to recognize that they live in a world with more complex “customer” relationships than most companies. Many organizations ask “who are our customers” and “what work are they willing to pay for” and get a pretty straightforward answer. A culture of waste identification and elimination can be built around answers to these questions. But these questions are harder to answer in government. There’s often an entire ecosystem of stakeholders who have special and potentially conflicting demands. Performance of a government agency can impact certain segments of citizens, the public at large, businesses who serve citizens, policymakers, legislators, and so on. What may seem like waste to one group may be viewed as essential by another. Anyone who has stood in line to get a driver’s license or applied for a home loan backed by the FHA can appreciate this dynamic. Government provides critical risk management functions to the public (i.e., in order to get a license or a home loan a person needs to meet certain requirements) yet these functions feel different depending on which stakeholder group you’re in.The case for lean? This is why we apply lean broadly. Complex customer relationships mean leaders need to spend more time fostering a dialogue about the values of their organization and the needs of various stakeholders. By being clear about which outcomes matter to each stakeholder, lean leaders begin to support their teams in aggressively removing obstacles that stand in the way of achieving those outcomes. Practices such as including actual end customers (i.e. a mortgage company that uses FHA to insure their loans) and other stakeholders in kaizen events and ensuring the “voice of stakeholders” are included in decision-making during annual planning or strategy deployment sessions – these are just a couple of ways a little bit of lean thinking can go a long way. Different needs across stakeholders don’t disappear, of course. Tensions always exist. Those opportunities for tension (and coordination) will just be that much clearer with active problem solving and open dialogue. Creative solutions that can eliminate waste and be win/win/win for multiple stakeholders will present themselves that much more often.

- Lean doesn’t help me achieve policy objectives”

Policy almost always requires implementation through an agency process or operation. One federal agency had a policy process that was widely considered to be ineffective, long, and painful. For example, issues frequently were discovered very late in the process, after incredible amounts of wasted staff effort.The case for lean? In the case of this particular federal agency above, the leadership group became so fed up with it that they succumbed to lean – they convened a kaizen-like event with the right mix of people with direct experience and knowledge, mapped/walked the process and reconceived it to address the root cause problems, and came up with some dramatic results. While the process continues to evolve, it is no longer considered a key challenge to achieving policy objectives. In this way, lean helps government organizations translate policy into efficient and effective operations that lead to results in the real world. Impact in the real world isthe very objective of policy.

So, what’s to be done? Delivering change in government does have its special challenges, certainly more than five, whether real or perceived. Resources are often constrained. Processes as well as customer relationships are complex. Leadership and policy objectives do frequently change. But the situation is far from hopeless. Lean management is one of the most practical and effective ways for leaders to create positive change. The biggest challenge for the lean community may be to tell more stories of lean management where it really is happening – where and how it’s being applied so it’s not as easily dismissed.

If you’re a leader in a government agency, pick an area that needs improving and experiment with lean approaches. If you need help, ask for it. Start small, see if you can make a noticeable and impressive difference, and build from there.