Among the many outcomes of continuous improvement practices is one that happens so frequently that it’s become a lean truism. Nevertheless, the result continues to surprise even the most advanced lean practitioners. That truism is that nearly every time you address an issue with lean thinking and practices, you not only make progress toward resolving it. You also uncover more issues to address — and sometimes unexpected ones. This consistent outcome reminds us that lean is about learning as much as it is about removing waste, resolving problems, and improving the work environment.

Such was the case with the partnership between the James P. Womack Scholarship and Philanthropy Fund (JPW Fund) and the California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly) in San Luis Obispo. The two organizations teamed up to advance the JPW Fund’s goal: to encourage innovative learning experiences in partnership with schools teaching lean thinking and community-based service organizations (CSOs) willing to provide gemba-based learning and improvement opportunities. (See “Making the World Better by Advancing Lean Thinking and Practice.”)

The partnership established two scholarships that offer students an at-the-gemba experience — hands-on practice of the lean concepts they learned in the classroom. The primary goal was to have the two interns analyze and improve core processes at a nonprofit organization, thus inspiring the organization to implement lean practices by showing them various methods to improve their operations.

Experimenting With Pilots

The Cal Poly internship scholarship program was one of two “experiments” the JPW Fund conducted to explore “lean internship” models. At Cal Poly, two interns worked 40 hours per week during the summer alongside the staff, embedded as workers who also demonstrate lean thinking and practices. The other, administered by the Pawley Lean Institute at Oakland University in Richmond Hills, Michigan, features a series of internships. The student intern pairs work 10 hours per week during a semester, leading lean continuous improvement efforts. (See “Unique Philanthropy Does Well by Doing Good.”)

A review of both programs serves as a reminder of how effective lean thinking and practices are in reducing waste and, in turn, improving the work environment and performance outcomes. It also demonstrates how the lean community can help CSOs adopt a lean mindset and practices that can help them help more people with fewer resources. However, it also suggests that lean practitioners may need to consider tailoring how they approach improvement to meet CSOs’ needs.

Exploring a New Way to Teach Lean Thinking and Practice

Eric O. Olsen, a professor in the Industrial Technology department at the University’s Orfalea College of Business who teaches lean thinking and continuous improvement courses, oversaw the JPW Fund internships at Cal Poly. In addition to the JPW Fund goals, he sees the internship partnership as an opportunity to offer students lean experiences at nonprofits similar to what the university provides at for-profit companies. Also appealing, he says, was that the internship partnership would give the nonprofit “access to this pool of talent with these kinds of skills where they would otherwise be priced out of the market.”

Olsen notes that the scholarship program also fits the goals of Central Coast Lean, a community of practice he founded and heads. With Cal Poly, the organization and its members serve as an ecosystem that teaches and promotes lean management in the area. For example, both organizations arrange for people to practice lean methods at the gemba to complete class projects or attain green and black-belt certifications. “The fact that we’re funding students to both learn and also help the nonprofit at the same time, I think that was a very attractive piece of this whole thing,” Olsen says. “So, the JPW Fund was a natural fit for us.”

The fact that we’re funding students to both learn and also help the nonprofit at the same time, I think that was a very attractive piece of this whole thing.

Eric O. Olsen, Professor, California Polytechnic State University’s Orfalea College of Business

Olsen awarded the JPW Fund scholarships to Strow Watson and Bianca Pugliese, both majoring in Industrial Technology & Packaging. Next, he relied on ad hoc networking to identify a nonprofit, choosing Transitions-Mental Health Association (TMHA) Growing Grounds Nursery in San Luis Obispo. TMHA provides mental health services throughout the Central Coast of California, including the Growing Grounds Nursery, which provides therapeutic horticulture socialization opportunities, paid employment, and soft job skills training for adults with severe and persistent mental illness. Clients work in the nursery that sustains TMHA by growing and selling plants to retail stores and landscaping companies. The choice of CSO was, in hindsight, particularly appropriate in the context of TMHA’s purpose, according to TMHA leaders. They note in a press release about the internship that “A fundamental insight of lean thinking is that by training every person to identify waste and effort in their own job and having them improve their work as a team by eliminating such waste, the resulting organization will deliver value at less expense while developing every employee’s confidence, competence and ability to work with others.“

Going to the Gemba

The internship began as most continuous improvement efforts do but with a twist. As usual, the students started by going to the gemba to gain a detailed understanding of the work and note potential areas to improve. However, instead of merely observing, they spent the first three weeks working side-by-side with the TMHA staff and its clients. “They were in the gemba, doing the work,” Olsen recalls. “They were planting and moving plants and selling things, so it wasn’t [only] specifically lean work.” He adds that this approach was “the real needle-mover, what made this project different from the others we had done and was a real improvement.” With the students going in every day and working with people in the organization, “they were building insights [about the organization’s work processes] and trust with the people in the organization,” Olsen explains. (Taking time to build trust is a lesson that any organization looking to introduce lean thinking and practices would be wise to heed.)

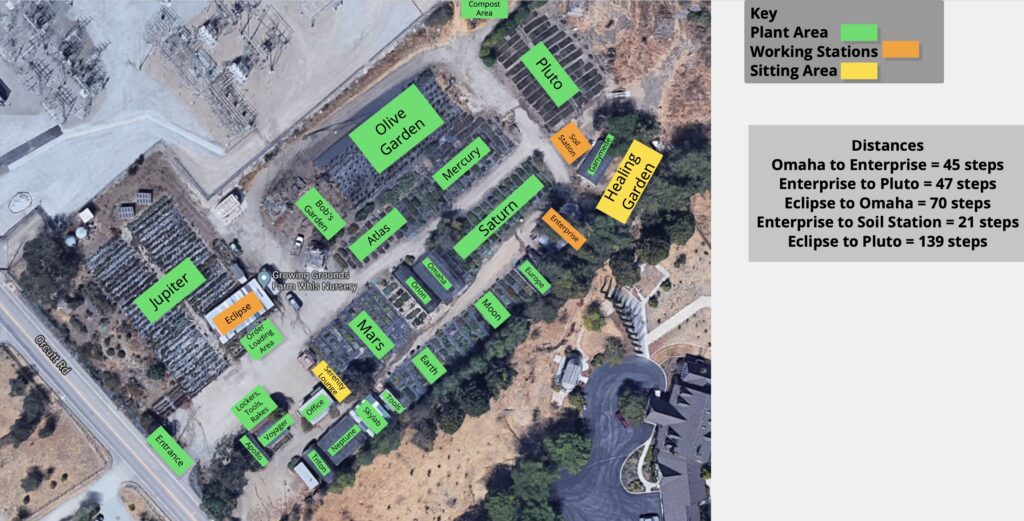

In addition to getting to know the work and coworkers, Watson and Pugliese conducted some preliminary analysis to gauge the scope of work, including counting inventory and mapping the nursery layout from a bird’s-eye view to get a sense of the overall work environment and distances between work areas.

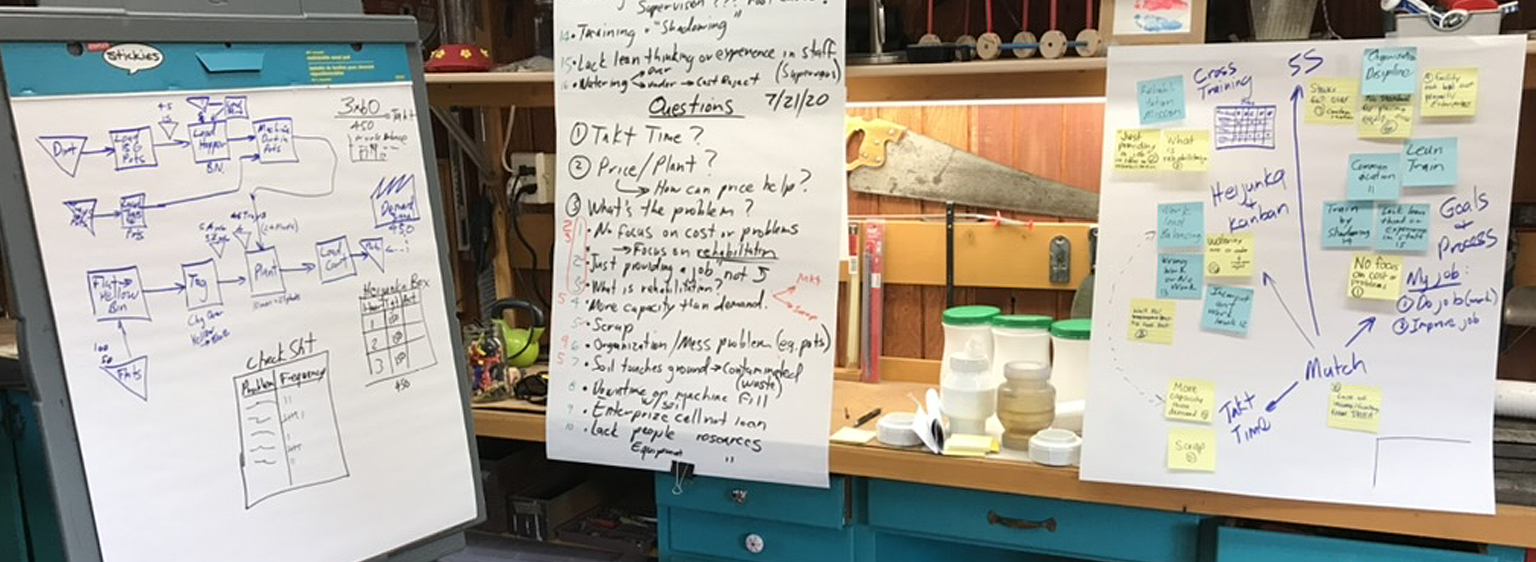

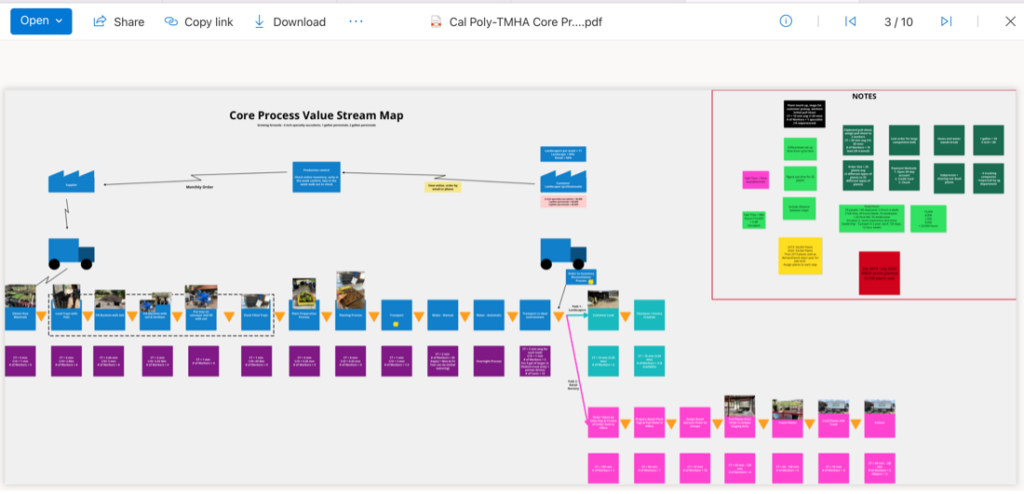

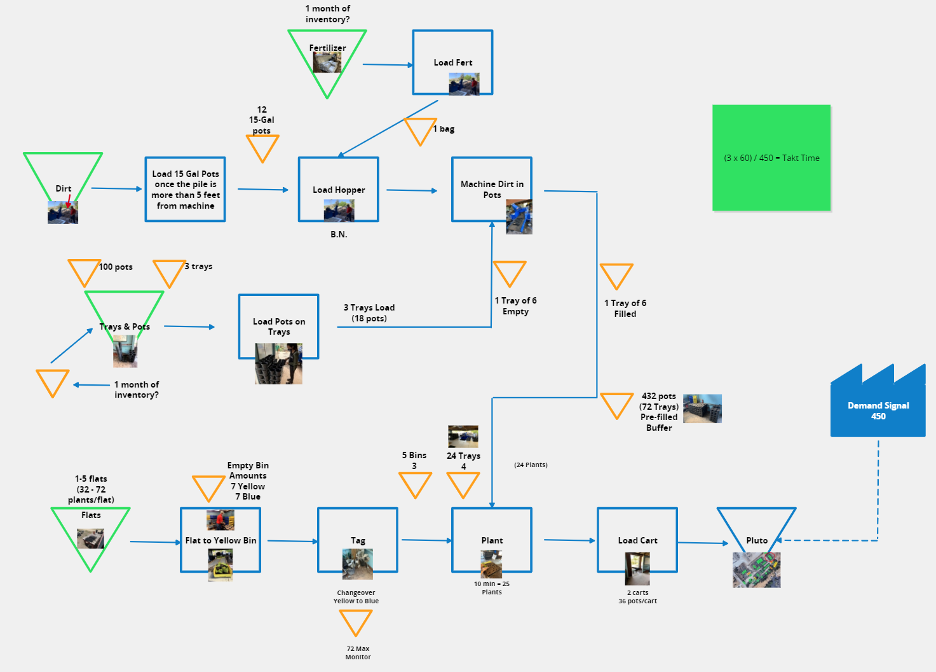

The interns also drew a value-stream map and analyzed the organization’s “core process” of producing four-inch specialty succulents and one- and two-quart perennials from the suppliers’ delivery of seedlings to the Growing Grounds’ delivery to landscapers and retail nurseries.

Conducting Demonstration Projects

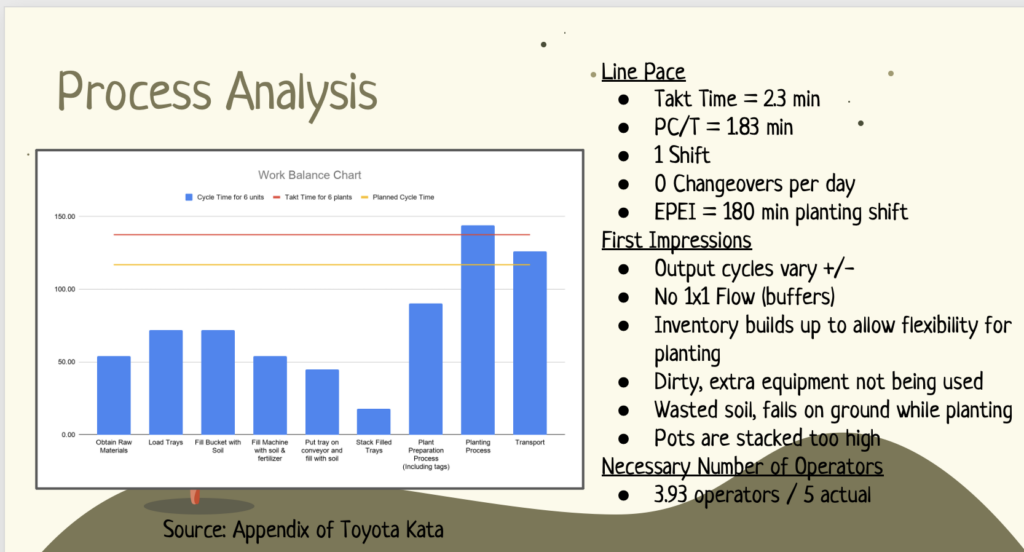

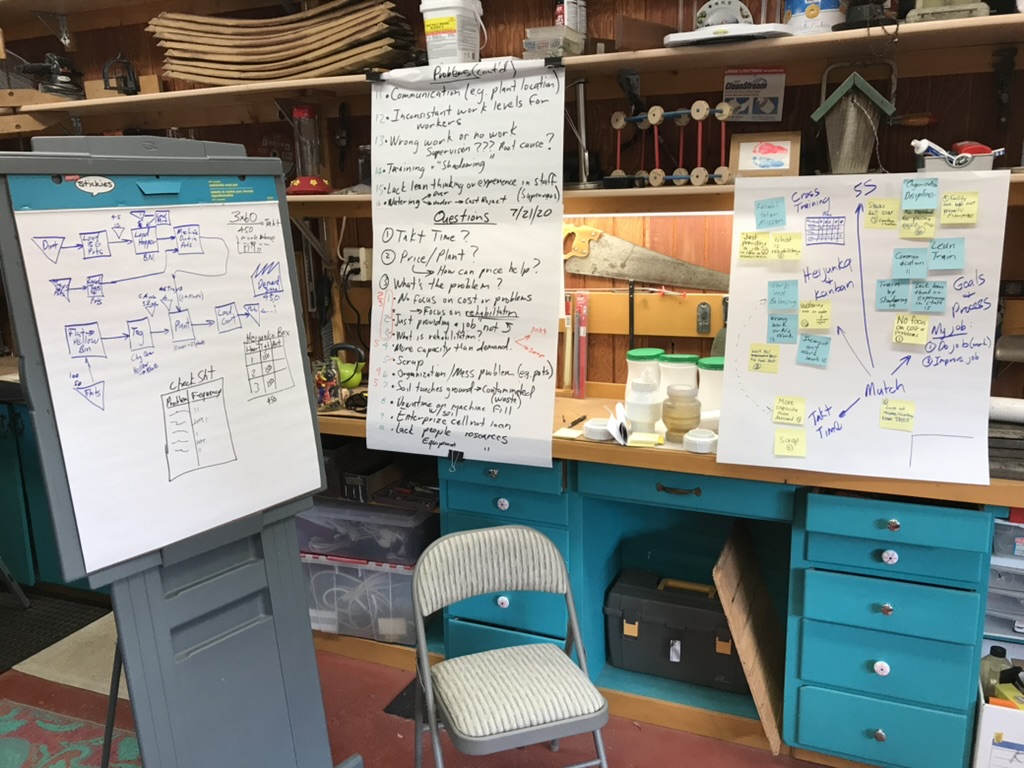

With the perspective gained from their hands-on work, the value-stream map, and process analysis, the interns, with the TMHA staff and Olsen, determined that the overall goal would be to target their efforts toward expanding production capacity. Since this was a learning experience for the interns and an introduction for the TMHA staff, the team did not identify a specific gap or state a particular goal, as is customary in lean improvement initiatives. Reviewing the current conditions using the A3 problem-solving process turned up multiple areas needing improvement. Still, the team zeroed in on addressing issues in the potting operation in the “Enterprise” building, which, Olsen recalls, has “more of a manufacturing cell feel to it.” So, it seemed the best area to conduct demonstration projects that would deliver significant performance improvement while offering good hands-on “practice for the interns and educating the staff.

During the potting operation housed in the Enterprise building, workers transplant seedlings from trays of 64 into 1-gallon pots, then take the newly potted seedlings to an area outside where they’ll grow to a size ready for sale to the customer.

A few specific issues the interns noted in their analysis of the area involved workplace organization and cleanliness, inconsistent work levels, and some confusion about work assignments. They also noticed a lack of standardized work documentation and training on work processes. As a result, addressing these issues became the focus of productivity improvement efforts, culminating in a pull system demonstration.

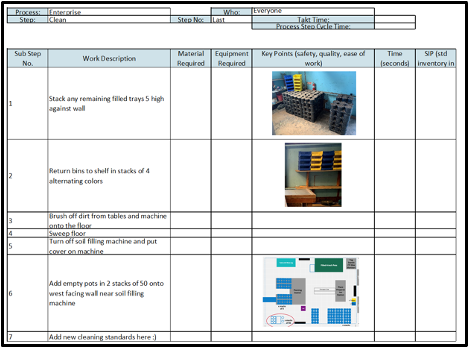

Clearing the Way for Improvement

First, Watson, Pugliese, and Olsen conducted a modified 5S project to improve work area organization and cleanliness. Unable to work with the TMHA staff due to a spike in the pandemic, the three cleaned and cleared the area, taking several items outside. Then, the staff took over, returning only those items they needed to the work area and disposing of the rest. The team finished by creating guidelines to show where tools, supplies, and equipment should go when not in use, including visually marking the locations. They also drafted an end-of-day standard operating procedure (SOP, aka standardized work) to keep the workspace clean and organized.

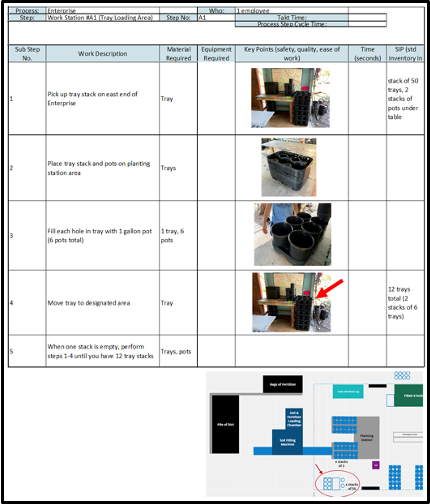

Other lean practices that the interns shared with staff included using the flowchart and gemba observation of the potting operation to define and set standardized in-process (SIP) inventory (also called SWIP for standardized work-in-process) levels at stations requiring work-in-process inventory. They also created standardized work documents to standardize training, govern day-to-day work, and sustain the 5S effort.

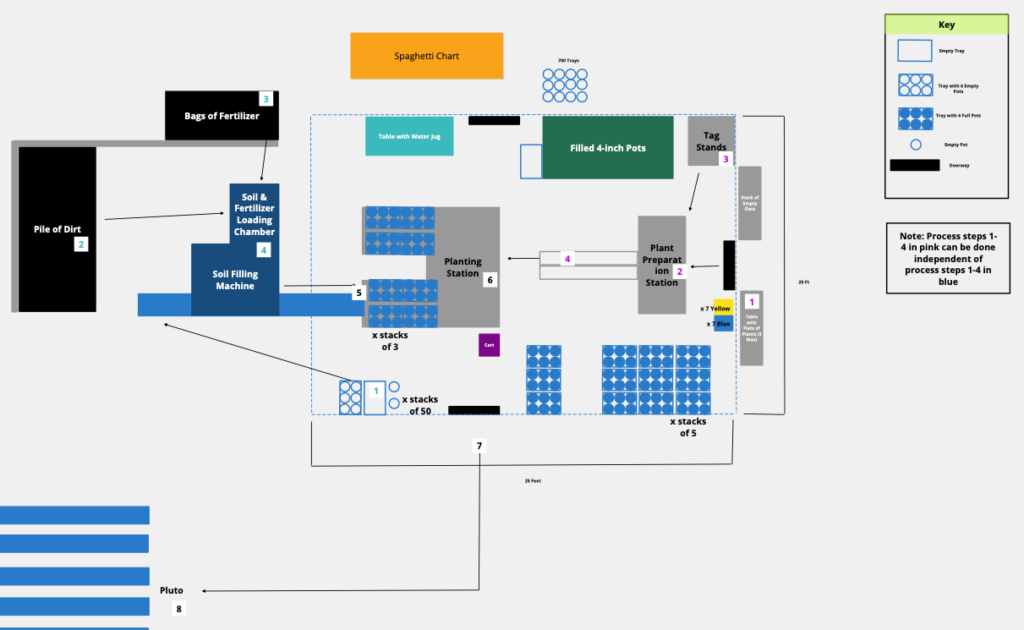

They also charted workers’ movements as they completed the work that, with the other analysis, led to a recommendation to change the order of tasks and rearrange communal workspaces to improve the work environment and maximize productivity.

For example, as the interns cleaned and organized the area, they moved the tables, intending to create one continuous flow cell from filling the pots to potting the seedlings. However, with the space cleared, the TMHA staff noticed that the work involves two processes that they could complete separately. They also realized that separating the two processes would allow them to put away the conveyor belt that leads from the machine to the potting table. Thus, they could free up space and create a walking path between the machine and the table, allowing more workers to simultaneously work at the potting table. Though such an arrangement does not adhere to the lean concept of continuous flow, it suits TMHA’s higher purpose of offering its clients a positive work experience. Having them work together on the same task serves that purpose. Also, the new arrangement helped the staff schedule workers more effectively, enabling them to ramp up the number of potters when orders spike or reduce them when they get fewer orders.

As a result, the team set up the room so the workers could complete the two tasks at different times, recommending that workers complete process A from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. daily, which would ensure that Growing Grounds has enough inventory of filled pots ready for planting from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Setting Up the Pull-System Demonstration

In final preparation for the pull-system demonstration, the interns walked through the process, marking inventory locations and levels and placing the SOPs at each station.

For the pull-system demonstration, Olsen and the interns walked through the entire process with empty pots, explaining how the work tasks progress through the steps, planting the requested number of plants with minimal waste or excess in-process inventory. They also shared a more detailed work process map. Though the interns did not implement a pull system, the demonstration was an opportunity to show its potential benefits. Also, organizing the work to flow this way gets Growing Grounds production closer to a true pull-system based on the pull of customer orders with each step completed at a calculated takt time that levels production and is visually controlled with the kanban system.

Perhaps most important, Olsen recalls, they’d posted the value-stream map and flip charts in the work area during the demonstration, asking the staff to write their ideas about improving the work process, emphasizing that they know best how to do so. Then, “we just had a nice hour-long discussion: ‘What do you think and what are your ideas for how to make this better,’” he says. “I think that was really the first time they said, ‘oh boy, we can’t wait to see what we can do.’ We got pretty good buy-in at that point.”

Wrapping Up and Reflecting on the Internship

At the internship’s end, the students delivered a presentation to the TMHA leadership summarizing the results and offering a list of several other work process improvement ideas for the staff to consider implementing. (See “Suggested Next Steps.”) Cal Poly, Central Coast Lean, and Olsen continued to support TMHA. For example, several other Cal Poly students completed class projects there, Central Coast Lean granted free access to learning activities, and Olsen led several monthly gemba walks with the nursery manager. Still, eventually, onsite activities ended without daily interaction due to complications from the pandemic and changes to TMHA’s leadership.

Overall, TMHA and Olsen rate the internship partnership a success, a three-way win for students, CSOs, and the greater lean community for the JPW scholarship approach. First, it offered students the real-world lean work experience necessary to fully comprehend and appreciate lean concepts and methods. Second, the internship also helped and inspired TMHA to learn and implement lean practices. Notably, the interns convinced the staff about the effectiveness of this new way of thinking and working. “My staff originally had a healthy dose of skepticism,” admits Frank Ricceri, TMHA’s now retired director of Vocational Programs. “But that skepticism vanished in about ten minutes once Strow and Bianca started to make their presentation. They had taken the time to work alongside us and understand what we do, and everything they presented made sense and was rooted in our reality. Above all, it benefited our clients—it made their work that much easier and that much more rewarding.”

My staff originally had a healthy dose of skepticism. But that skepticism vanished in about ten minutes, once Strow and Bianca started to make their presentation.

Frank Ricceri, Retired Director of Vocational Programs, TMHA

Finally, it offered the JPW Fund the information it seeks in trying to identify ways to teach students about lean management by providing them at-the-gemba hands-on experience with lean thinking and practices.

Adjusting to Meet a Different Core Purpose

Still, as Olsen reflected on the experience, he realized that, in the future, when helping an organization like TMHA learn and adopt lean thinking and practices, he’d recommend taking a bit of extra time thinking through the organization’s core purpose. For example, though Growing Grounds Nursery’s most visible value stream is its work process — planting, growing, and preparing plants for sale and then selling them — its more significant value stream is the help it provides clients. TMHA’s primary purpose is to help people struggling with mental illness. So, the nursery’s role is to help fund this work while providing job experience and opportunities for people needing transition services.

“It’s not only about getting more plants out there and making money, but it’s also about developing the people at the same time,” Olsen says. “I understand they could be very compatible goals, but I think we need to scratch our heads a little more about what we emphasize and how we approach that piece of the challenge.”

I don’t know how many times I have to learn that it’s always about learning.

Eric O. Olsen, Professor, Cal Poly

Olsen muses that he thinks identifying this new “people part” of the TMHA internship contributes to moving the JPW Fund internship forward. Though “people development” is a pillar of lean thinking and practice, the goal takes on new meaning in the work TMHA does. “The group overseeing the JPW fund said, ‘we’re not only going to do something, but we’re going to find something about how we’re going to do this,’ Olsen notes. “Moving into the future, maybe that means we go this way, instead of that way.” Overall, he adds: “We did some good stuff, and I’m asking: What do we do next time? How can we do it a little better? I don’t know how many times I have to learn that it’s always about learning.”

| Suggested Next Steps |

|---|

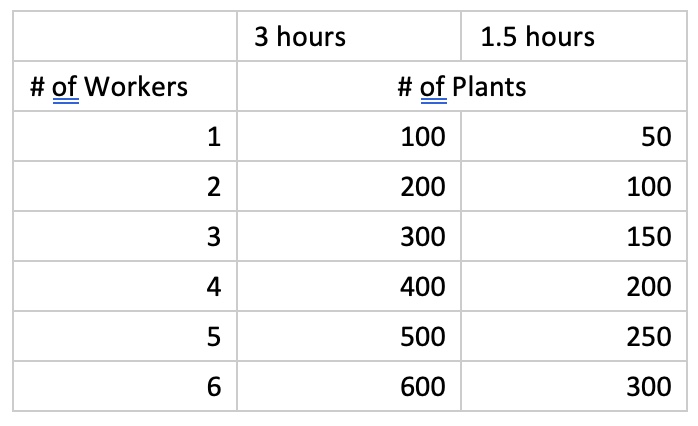

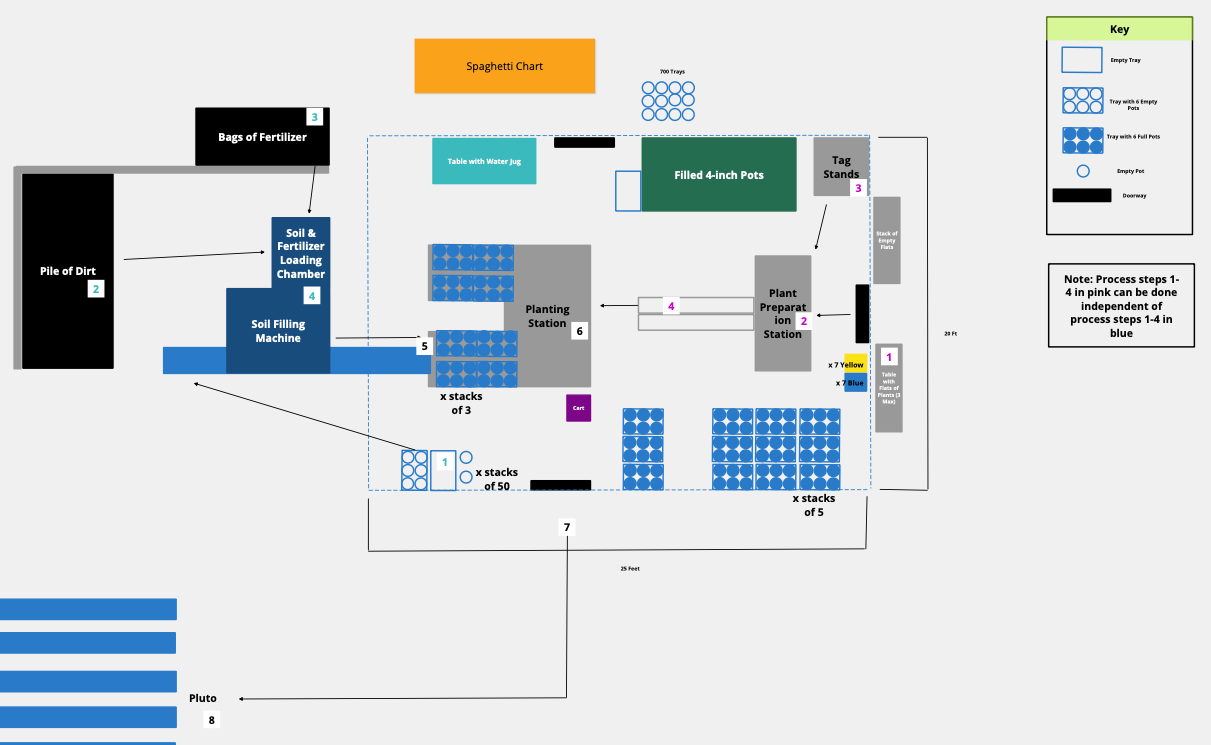

| Among several improvement ideas that the interns suggested for future implementation are the following: 1. Use the Tractor to Reposition and Maintain the Quality of the Soil A TMHA associate suggested using the tractor that’s available onsite to maintain a FIFO system for the soil. The current process adds the new soil to the front of the pile, where the person filling the potting machine retrieves it. However, with this approach, the soil in the back dries out, becoming unusable. By moving the old soil to the front and dumping new toward the back, THMA will maintain a FIFO system that ensures soil quality. 2. Create a “# of Workers vs. Output Matrix” to Help with Scheduling Creating a chart showing the number of plants a worker can pot per shift will help TMHA staff schedule the appropriate number of workers to meet output requirements.  3. Change Workstation Labels  Since Growing Grounds staff now considers the potting process as two separate processes, it should change each workstation’s label accordingly. Relabeling the work tasks this way would become the new current state, which will help staff better understand the work as it works to improve it. Currently, the two processes are labeled one through four in either pink or blue. With the new approach, the workstations/tasks associated with process A, the loading-the-machine process (numbered 1 through 4 in blue on the left side of the image above), should be labeled as follows:: + Take trays from the pot tray stacking workstation (inventory) to conveyor leading to soil-filling machine – change from blue 1 to A1 + Transfer soil from inventory to soil and fertilizer loading chamber – change from blue 2 to A2 + Transfer fertilizer from inventory to soil and fertilizer loading chamber – change from blue 3 to A3. + Operate soil filling machine – change from blue 4 to A4 + Place the soil/fertilizer-filled pots on the planting workstation, where they are ready for the next potting session – black 5 Then workstations for work process B, the potting/planting process (numbered one through 4 in pink on the right side of the image), should be labeled as follows: + Move the seedling flats to the “yellow or blue bins” workstation – change from pink 1 to B1 + Take seedlings to the plant preparation workstation – change from pink 2 to B2 + Move tag stands to the plant preparation workstation – change from pink 3 to B3 + Transfer the tagged seedlings to the planting workstation – change from pink 4 to B4 + Transplant the seedlings into the soil/fertilizer-filled pots – black 6 Operators place the newly potted seedlings on the cart (magenta-colored box) to the side of the planting workstation, then wheel them out to the Growing Grounds, where they mature until they are ready for sale. |

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.