The typical restaurant kitchen wastes more than food. Time, motion, excess labor, and ultimately profits go into the dumpster. For example, a kitchen usually has a cook at each station plus prep cooks handling bulk side dishes. The layout creates lots of running around and forces close contact, not distancing, as people dash in and out of the walk-in coolers and dish room.

Using a few basic continuous improvement tools to better understand the actual work of people in a kitchen, Matt Savas, a team leader at the Lean Enterprise Institute and a fervent neighborhood restaurant foodie, offers a sweeping alternative way to run kitchens for better safety and profitability.

Covid-19 has brought devastation to nearly every industry. Perhaps the closest hitting to home – at least mine – is the food service industry. I enjoy the conviviality restaurants bring to community life and the joy they provide to customers. Those that have survived through the lockdown now face major challenges with reopening, namely safety and profitability. How can these businesses protect their workers and customers? And how can they make money given capacity constraints and consumer hesitancy to dine out?

This article does not claim to offer final solutions to these major challenges. However, it does offer ideas on how to use simple continuous improvement tools to see where safety and cost problems exist, as well as how to generate ideas on countermeasures.

Let’s consider a typical commercial kitchen during morning prep. There is a cook for each station – oven, sauté, pantry, fry, and grill – gearing up for the lunch and dinner services ahead. Plus, there are two prep cooks handling bulk prep items such as rice and potatoes that will find their way to most entrées. The layout is fairly simple with a dish room and three walk-in coolers storing prepped items and raw ingredients such as fish, meat, and produce. Here is what their movement could look like.

As each cook is responsible for prepping the tools and raw ingredients for a successful service everyone is running about. This forces close physical contact, particularly around the walk-in coolers and the dish room. There is no control over worker movement, jeopardizing their safety. Moreover, the high number of cooks stresses labor cost.

Let’s consider a very different morning prep environment with just one prep cook and a runner. The prep cook is responsible for both bulk and station prep. The runner is responsible for delivering ingredients and recipes to the prep cook. This reduces the number of workers by five, alleviating cost and density of labor in the tight kitchen during busy morning prep. And it isolates motion to a single worker, thereby enabling management of physical contact. Here’s what this new kitchen could look like.

Assigning bulk and station prep to a single cook may appear impossible. Can one person do the work of seven? To answer this question, it’s important to understand exactly what work is. Let’s watch a quick video to see what work is in the context of the prep cook.

With an understanding of work, it’s time to look at the story of prep. What exactly must the cook prepare and what time is available to prepare it?

But it’s diving into the details of each of these jobs that reveals opportunities for improving the work and transforming the prep system. Let’s take a deep dive into one job: making crudito.

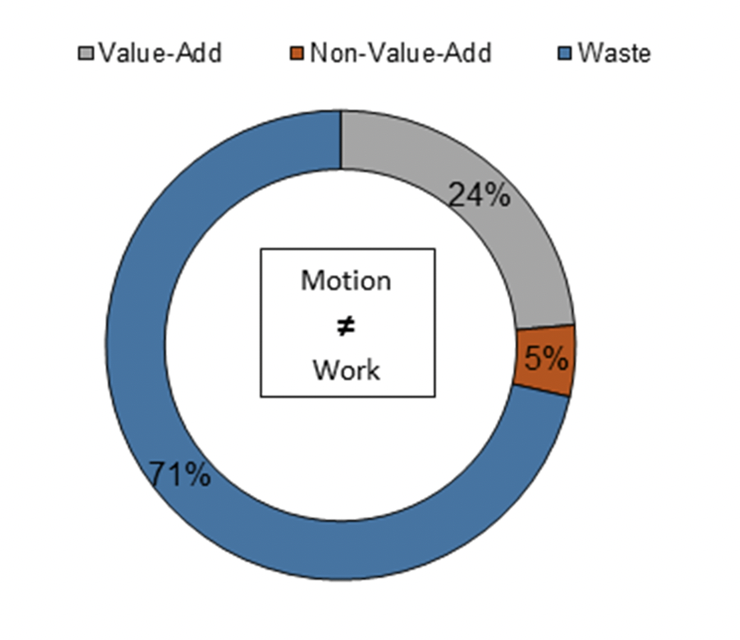

By mindfully observing the work of prepping crudito, we learn that 71% of the motion attributed to this job can either be eliminated or assigned to another worker, in this case the runner. Tools and ingredients could be stored at the station. If space constraints or need for refrigeration demand storage in another location, then the runner could deliver them. Labeling, wrapping, and storing could also be assigned to the runner, allowing the prep cook to move on to the next prep item without interruption. These simple changes could turn a 5.4-minute job into a 1.5-minute job. Undoubtedly, similar opportunities exist across each of the other prep items. By observing the work deeply through the pie diagram shown below, it’s possible to see opportunities to create capacity.

Let’s tie it together and brainstorm how the runner could capably support the prep cook. The key is knowing what to bring and when to bring it. This ensures the prep cook is making the right items at the right time. When the station cooks arrive they’ll be set up for a successful service.

I will reiterate that this article is not meant to offer final solutions. It is meant to offer ideas on how to confront the problems restaurants are facing. The substantial concerns over safety and profitability will challenge the industry to think and act differently. Let’s start tackling those challenges by understanding the work and redesigning it for safety and business prosperity.

Next Steps:

Learn more about two improvement tools used in the story:

- Spaghetti map

- Operator balance chart (The example used in this article is crude. Breaking work down into essential work elements as outlined in the crudito video)

- Then read the new book Steady Work, which explains how to implement a continuous improvement system in fast food restaurants that eliminates waste as it improves work, the work environment, and business results. Download a chapter.