Many of us have read news stories discussing ethanol as a cheap, clean, and viable alternative to gasoline. To meet the ever-growing demand, players throughout the ethanol supply chain have had to find new means of efficiency and productivity – from the farmers who supply sugar cane, all the way up to ethanol distributors. In one memorable lean project, Carlos Moretti found himself assisting a Brazilian sugar-cane supplier for the ethanol industry with a number of efficiency and quality problems. This is his story:

First, some background on the implementation. What is Brasil Canasul and how did they first approach you? What problems were they having?

Brasil Canasul is a company with 250 employees, in the state of Goiás, Brazil. In 2011, they closed a contract with one of the biggest players in the Brazilian ethanol market and, in order to fulfill the client´s requirements of production (hectares of sugar cane planted per day), they would have to introduce a third shift. After six months, they noticed that their productivity wasn´t good enough, the downtime level was getting high, the staff turnover rate was increasing, the quality was poor (employees were having a hard time dealing with the onboard computers), and of course they had lots of clients complaining. By that time, the managers concluded that something should be done and fortunately, one of the managers read an article about the Toyota Production System (TPS) in a business magazine and wondered whether that system could help them.

I understand that your first priority was making the work and the problems visible. How did the nature of the work at BC make this difficult?

By the time we started the project, we had already been in many kind of gembas: factories (painting shops, stampings, aluminum injection, seats, medications, food, and pet food), offices (insurance companies, HR departments) and so on. What do these gembas have in common? You may see “where the gemba begins and where it ends.” I mean, you have rooms, floors, elevators, etc., but you still are able to make a gemba walk on your feet. At Brasil Canasul, every three or four days the teams were in a different gemba with 30~35 ha (1 ha = hectare is the area of a soccer field), with different topography and sometimes different soil and weather conditions. So the challenges were:

- How do we define the standards when the gemba conditions vary so much? In other words, how much sugar cane could be planted on a given day? (At the beginning, they only measured the planted area in a monthly basis.)

- Due to the gemba’s dimension, how do we measure the work in order to see whether we are running ahead or behind the plan?

So, in a nutshell, the main issue was: No standards, no problems!

What were some solutions you implemented to make the work visible?

In order to answer this, let me first explain the process of planting:

- Workers harvest the whole sugar cane stalks with a harvesting machine

- The machine cuts the full stalks into smaller pieces, which are placed in the “bucket” of the truck (see photo)

- The trucks carry the stalks to the planting areas

- When the trucks reach the planting area, the stalks are put in planters

That said, our genchi genbutsu revealed that it took four bucketloads of stalks to plant one hectare. So instead of trying to measure the area planted per hour, we started counting boxes planted per hour.

As a problem is a deviation from a standard and our goal was to make problems visible “immediately,” the next step was to define the plan; in other words, how many “boxes” we would plant on a given day. In order to do so, every day a team member would define the number of boxes that had to be planted the next day, considering the area size and the area conditions, such as topography, soil, etc.

After this system started to run, we built a Process Control Board, and every hour – by radio – the team members reported the number of “boxes” planted and, if they did not achieve standards, why they did not meet the target.

Did you encounter much resistance/skepticism from the workers when this happened?

Oh yes. Something we’ve seen over and over again is that people will always complain when you try to change the status quo. Sayings like “I´ve been doing this that way, all of my life! Why do you want to change it now?” or “It works for Toyota because they are Japanese, but we are Brazilian (or Mexican, or American, or Polish…)!” are heard every time we start a project. And why does this happen? In his book “Change or Die,” Mr. Alan Deutschmann states that when we find ourselves in a seemingly intolerable situation, our minds activate many mechanisms to help us cope with it. These mechanisms were studied by Sigmund Freud, who called them “ego defenses.”

At Brasil Canasul it was no different. When we started measuring the production on an hourly basis, the workers felt overwhelmed and started to complain: “Why are you measuring us?”, “Do you think that we do not work well?”, or my favorite, “Do you think this is an assembly line?” These kinds of complaints are anything but ego defenses such as denial and rationalization (coming up with creative excuses to cover up the real motives of why we don’t want to do something).They were resisting to change. As Mr. John Shook stated, “(…) the way to change culture is not to first change what people think, but instead to start by changing how people behave – what they do”[1].

So, the challenge was to convince workers to do the process the way we proposed. We ended up asking a small team of first-shift workers for the benefit of the doubt: “Please, do as we say, for at least one month. We are sure that the results are going to be great!” After two or three months of the machines staying cleaner (5S), the workers being able to see whether they were ahead of or behind the schedule (jidoka) and the production targets having been set and understood (visual management), the productivity increased a little. As a result, workers from the other shifts asked to attend lean trainings.

What problems emerged once the visual management tools were in place?

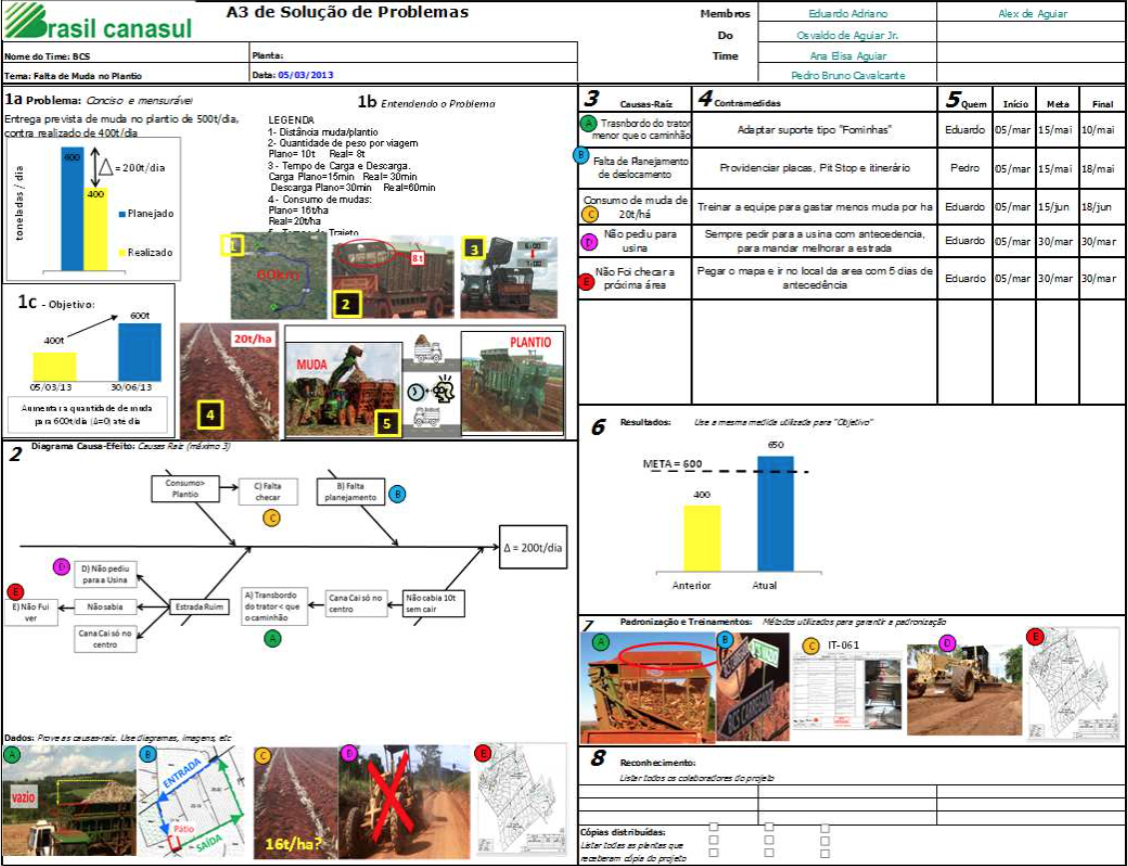

Every time the production teams did not achieve their target, the team leader registered the reasons. After two or three months, we could see that there were two main problems preventing us from achieving the targets: Machine downtime and lack of stalks. We developed A3 problem solving reports to address both problems (but that’s a story for another time).

What results came out of the full transformation?

We’ve been with Brasil Canasul for two years. On the first year, the average monthly planted area went from 770ha per month to 920ha per month. After the second year, the average monthly production was over 1000 hectares.

[1] “How to Change a Culture: Lessons from NUMMI,” MIT Sloan Management Review – Winter 2010