Last week we ran two articles on the history of, as well as reflections on, A3 thinking. Given the popularity of these pieces, it seemed right to provide even more background on the topic, one of the better-known aspects of lean thinking. A3 reports have become one of the most popular lean tools today, a way for people and teams to work together to solve problems; and their widespread adoption could easily be viewed in lean terms as…a problem.

Tools often provide traction for getting started with lean practice, and A3s often deliver immediate results. The A3 ‘problem’ (a gap, in this case, between the intended purpose and actual usage) echoes the broader challenge facing widespread adoption of any proven TPS methodology: moving from lean tools to lean management, according to Jim Womack. As he notes, “Tools—for process analysis and for management—are wonderful things. And they are absolutely necessary. And managers love them because they seem to provide shortcuts to doing a better job. But they can’t achieve their potential results, and often can’t achieve any results, without managers with a lean state of mind to wield them.”

Let’s keep in mind the purpose of A3s, from the Introduction to John Shook’s key book on the topic, Managing to Learn (MTL).

“Writing an A3 is the first step toward learning to use the A3 process, toward learning to learn. Some benefits in improved problem-solving, decision-making, and communications ability can be expected when individual A3 authors adopt this approach.”

All well and good. Unfortunately most organizations stop there, and don’t proceed to the next step. As Shook cautions, “unless the broader organization embraces the broader process, the much greater benefit will be unrealized. The entire effort may degenerate into a ‘check-the-box’ exercise, as A3s will join unused SPC charts, ignored standardized work forms, and disregarded value-stream maps as corporate wallpaper.”

So what exactly are A3 reports? A3 reports are a way of structuring and sharing knowledge that enables teams and their members to practice scientific thinking as a way of discovering and learning together. The tool promises immediate benefits by helping people structure and design more effective approaches to problems (framing them in solvable ways, taking a data-based approach, using root-cause-analysis to find the point of origin for problems (gaps), encouraging careful problem analysis over quick abstract “solutions,” and so forth).

Definitions include:

- A storyboard

- 5S for information

- Standardized story-telling

- A “visual manifestation of a problem-solving thought process involving continual dialogue between the owner of an issue and others in an organization.”

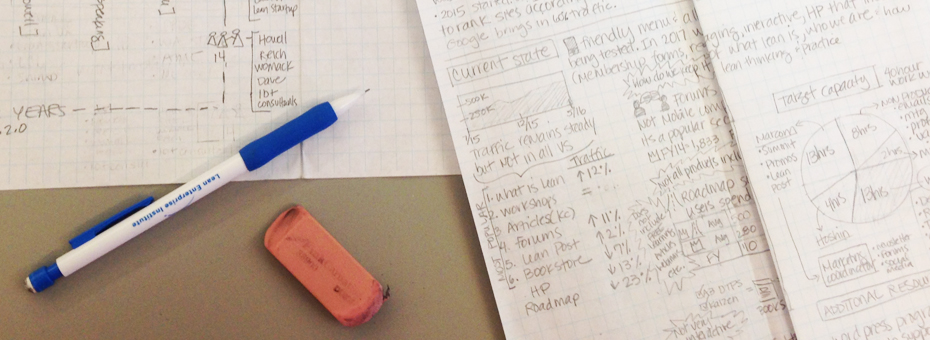

They are all that, and more. Essentially, A3 reports, named for the international-sized A3 paper (a larger page of roughly 11 by 17 inches), enable people in organizations to capture issues through a commonly understood template, permitting people to see problems through the same lens. The sequence is designed along the logic of scientific thinking—the PDCA cycle at the heart of lean thinking. You can download A3 templates from LEI here.

The basic thinking process captured by this format is relatively simple, and has been around in many other forms and formats for a long time. There are different types of A3s, according to the situation. But don’t work too hard to find the precisely right format; in fact, veterans such as David Verble stress the importance of starting your A3 not by writing but by thinking.

“The most fundamental use of the A3 is as a simple problem-solving tool. But the underlying principles and practices can be applied in any organizational setting. Given that the first use of the A3 as a tool is to standardize a methodology to understand and respond to problems, A3s encourage root cause analysis, reveal processes, and represent goals and actions in a format that triggers conversation and learning,” says John Shook in this piece sharing his purpose for writing MtL.

There’s no doubt that those with deep experience have found great power in A3 practice. For example, lean veteran Gary Convis says that he, “used the A3 format as a way of seeing inside the minds of the 113 plant managers,” citing his experience at Dana Holdings Corp, as well as elaborating on using A3 problem solving to make the thinking process visible.

Toyota veteran Tracey Richardson shares a hugely practical step-by-step tour of the A3 thinking process in her great article Create a Real A3, Do More than Fill In Boxes. In so doing she explains how an A3 is “a way of thinking with deeper benefits, a process based on the PDCA (plan, do, check, adjust) cycle designed to “share wisdom” with the rest of the organization.” Another terrific A3 “stroll” is provided in this recent piece by Jon Miller.

Tracey complements her brief user’s guide with a piece that suggests you Test Your PDCA Thinking By Reading Your A3 Backwards as a way of avoiding a common A3 hazard—jumping to conclusions.

When given a problem to solve, most individuals rush to provide the bestest solution the fastest. Yet the nature of A3 thinking requires careful framing of the problem, rigorous analysis of a clearly defined (and improvable “gap”), patient observation at the source, and real dialogue with the people touching the problem.

The A3 form exists to capture and document this material; it is not a formal document in and of itself. “If you’re ‘doing’ or ‘filling out’ an A3 behind your desk, I can say most of the time you will not be able to answer the questions above [listing the cause and effect logic of an A3],” says Tracey.

It’s worth noting that while there are different types of A3 reports, it’s useful to recognize that “not every situation requires an A3,” according to Norbert Majerus of Goodyear. In To A3 or Not to A3, he proposes a situational application that avoids a one-size-fits-all tool mindset. Specifically, he explains how the cynefin framework developed by Dave Snowden and Mary Boone can help navigate the different situations in one might apply A3 thinking.

Some argue that good problem-solving is not about having the right answers; it’s about practicing a useful, and commonly understood approach to thinking about thinking (learning). “Never lose sight of the thinking process that enables you to complete an A3—which then serves as a way of capturing, communicating, and building on what was learned,” says Tracey in A3: Tool or Process? Both…

In deepening this thinking-process through “A3 Mind,” you and your teammates can learn to activate what Daniel Kahneman calls both “fast” and “slow” thinking, says Michael Balle. “The key is to look at A3s as a physical support for managerial relationships based on expertise and teaching,” as a way to sustain A3 thinking in your organization, he notes. Such a shared approach can bring about a core lean goal: helping a problem-solving culture take root.

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.

I have just purchased the Managing To Learn book. I wish to create a War room / Critical Thinking / Problem solving Room. Can you please provide any Training Material, Templates or cartoons etc, that I can print off and create a Lean thinking environment. Do you offer any multi buy discounts to purchase the book ISBN 978-1-934109-20-5 ?

I have been a great fan of your org for decades.