Help wanted! The poster seems to cover every restaurant window. Those that have survived the pandemic now face a new challenge: a labor shortage.

Restaurants are trying to attract workers with higher wages, a positive development considering the industry’s notoriously low pay, but even that is not attracting enough staff. Besides, absent productivity gains and/or other cost reductions, paying food service staff more could result in higher prices that turn off customers.

How can restaurants have it all – pay their staff more, keep their customers by avoiding price hikes, and successfully serve them with the workforce available? In the longer term, technological innovation may help. But today, lean offers practical ideas – call it “work innovation.”

We recently paid a visit to a restaurant group trying to solve the problem with lean thinking. They’ve begun by simply asking how to make a sandwich.

We visited the commissary where they make sweet and savory items shipped daily to local shops. There, the company’s culinary director, a few months into the job, has begun to introduce lean thinking. His former employer (also a restaurant group) previously partnered with LEI to improve kitchen operations. Success at his old company has convinced him that lean thinking could offer solutions to the labor problem at his new company. He saw a potential quick win – and an opportunity to educate staff – in sandwich assembly, a simple but resource-intensive operation.

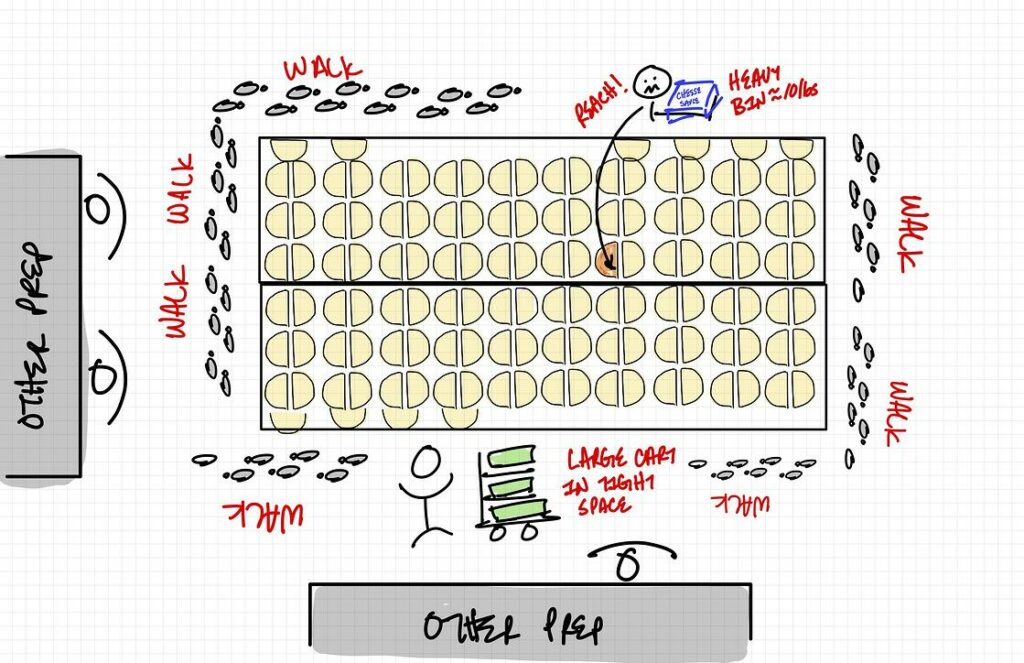

The commissary makes two kinds of sandwiches. Two workers make each sandwich in batches of 65 about 10 times a day. Why 65? Because 130 slices of bread can fit on the two stainless steel tables in the dedicated yet crowded work area. The workers start by retrieving all the ingredients required to make the sandwiches, necessitating walking to and searching through coolers located on the other side of the commissary. Then they lay out the slices of bread, scoop and spread sauce on every other slice, scoop and spread relish… You get the idea. Thirty-four minutes later, 65 sandwiches are ready for storage because they won’t ship until the following day.

The company was aware of space and food safety issues, such as holding cooked product unrefrigerated. They were less aware of the burden placed on the workers. For instance, the worker scooping the sauce had to cradle a 10-pound bin in one arm while shuffling around and reaching over the table to scoop with the other.

To grasp the current condition and imagine a better future state, the director and a supervisor captured cycle times of each step:

- Gather ingredients

- Place two slices of bread on the table

- Scoop and spread cheese sauce

- Place and spread marinated vegetables

- Place and spread roasted meat

- Place and spread seasonal relish

- Fold sandwich

- Store sandwich in delivery bin

They then multiplied the sum of the lowest repeatable cycle times by 65 sandwiches to get a theoretical total time to make them. The calculation revealed a potential time saving of 50%! Why? Because the job contained a lot of motion (walking around the table, reaching for sandwiches in the middle of the table, bending to pick up products, and twisting around other workers), which does not equal work (actions that directly and indirectly create value for the customer).

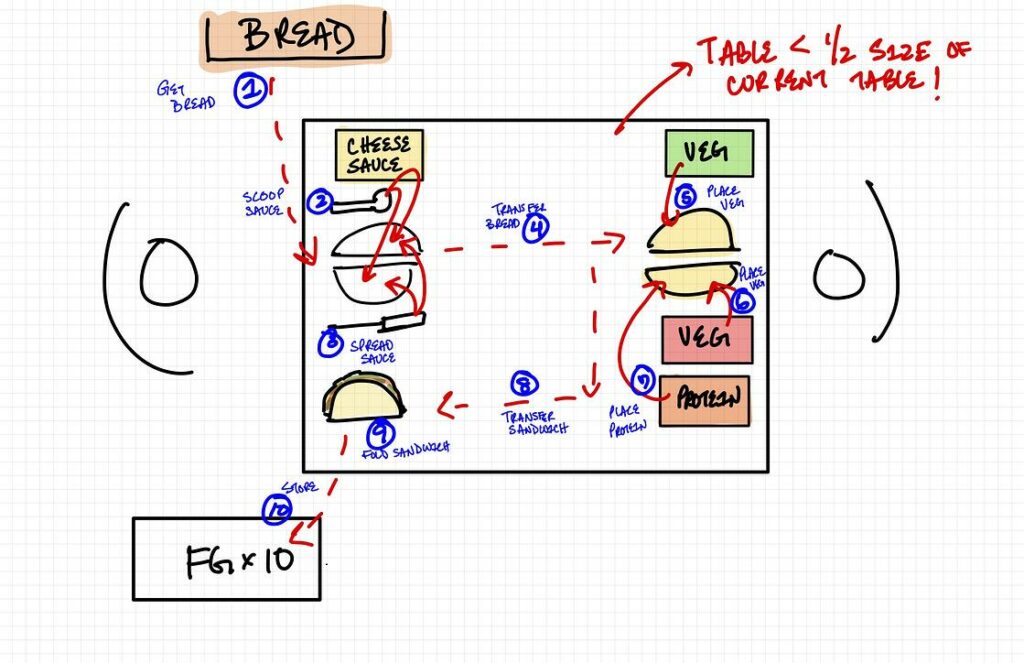

Realizing the opportunity, the supervisor and two workers began to innovate the work! Within half an hour, they simulated making sandwiches one-by-one. To eliminate the motion that wasn’t transforming ingredients into a sandwich – the waste – they experimented with re-positioning the tools and products, reordering the work sequence, and coordinating the handoffs. For instance, they moved ingredients from large bins that took up lots of space to smaller containers, which allowed them to have everything they needed immediately at hand, thereby eliminating reaching, bending, and walking. A silly but helpful mantra they kept asking themselves was, “Could a stubby-armed T-Rex do this job?”

While they attempted assembly with just one worker, they quickly realized a quality issue: the worker who added the relish couldn’t handle the bread because their wet hands would make it soggy. Ultimately, they settled on a setup with workers on opposite sides of the table with the sandwich moving between them in a U-shaped flow. And the one table took up less than 25% of the space formerly taken up by two tables.

Moreover, their rapid experimentation increased productivity by 29%, inspiring them to tackle other operations. As important, the new setup was far more comfortable for the workers because there was no heavy lifting or bending and they could achieve a rhythm. It’s important to note that their early productivity gains will not lead to fewer workers, as the revised routine requires them to repurpose a worker into a “water spider” to frequently replenish materials at this workstation and others they will transform in the future.

They also reduced the assembly lead time from 34 minutes to 24 seconds. This prompts the question of why make sandwiches in a big batch the day before and far away from a customer placing an order? A question for a larger experiment in the future, perhaps. For now, the lead-time reduction does eliminate the need for new in-process refrigeration because cooked product will not be left out in the open for unnecessarily long. Because a bin holds 10 sandwiches, finished product will be left out for no longer than four minutes. And the small-ingredient containers hold about 20 portions, meaning the ingredients will only be left out for about 16 minutes (assuming they have a working pan and a replacement pan).

While the restaurant industry, and perhaps yours, anticipates technological innovation that will solve its most intractable problems, this quick experiment suggests that innovating the work offers a practical approach to addressing the industry’s labor shortage problem today.

Join LEI’s online workshop Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata to learn a method for rapid experimentation to solve complex problems. Learn more and register here.

Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata

Develop Scientific Thinking, a Foundation of Lean Management in the 21st Century.