If you’ve ever lost sleep over a particularly frustrating source of waste in your organization, you’re not alone. Some forms of waste are easier to eliminate – others are so hard that they start to blur the line between “challenging” and “enraging.” Today we feature three experienced lean practitioners with the most frustrating types of waste they’ve encountered, plus their favorite tips for eliminating them.

Angela O’Hara (Senior Lean Facilitator, Scripps Health)

In healthcare, “overprocessing” seems to be the most tenacious type of waste to eliminate, in part because it’s difficult for the ones doing the overprocessing to self-identify. The discipline—nurse, pharmacist, physician—doesn’t matter; no one enters this field intending to take actions that aren’t valuable to the patient he or she has pledged to help heal. And yet our processes are riddled with activities that may feel from a single function’s perspective to be advancing the patient’s progress, but when viewed through another lens can be seen for the waste they are. (Some examples of overprocessing might include multiple locations to document, redundant forms, repetitive questioning, etc.)

In healthcare, “overprocessing” seems to be the most tenacious type of waste to eliminate, in part because it’s difficult for the ones doing the overprocessing to self-identify. The discipline—nurse, pharmacist, physician—doesn’t matter; no one enters this field intending to take actions that aren’t valuable to the patient he or she has pledged to help heal. And yet our processes are riddled with activities that may feel from a single function’s perspective to be advancing the patient’s progress, but when viewed through another lens can be seen for the waste they are. (Some examples of overprocessing might include multiple locations to document, redundant forms, repetitive questioning, etc.)

Early on at Scripps Health, we recognized the need to create “waste watchers” when trying to improve processes to increase flow, but labeling someone as such is only the tiniest first step in learning to see. We use a strategy that Amazon’s Jeff Bezos employed as a way to keep the customer top-of-mind in management meetings. He brought an empty chair to the conference table as a physical representation of the customer whose needs should be a constant focus. In a recent four-day event at one of our hospitals, we opted instead to fill the empty chair with a former patient to act as a member of the improvement team tasked with shortening the “discharge to home” process. This former patient proved instrumental in helping the team recognize the inadvertent contribution they were making to delay his discharge home—the only place he wanted to be after a frightful, unexpected, emergency stay at the hospital.

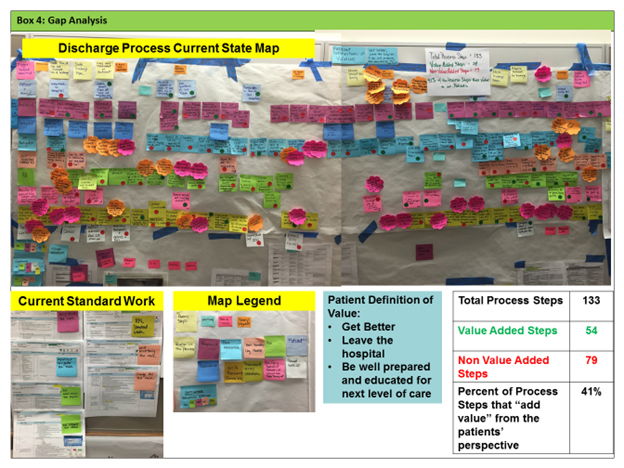

First, we had the patient help the team define “value” (get better; leave the hospital; be well prepared and educated for the next level of care). Then, after mapping the long and complicated current state process and much observation in the gemba, we used his clear definition to gauge each step as either value add or waste. Understandably, members of the care team initially defended their steps as adding value, but when held up against the simple, powerful definition expressed directly from the patient they vowed to serve, the defensiveness fell away. In a process with 133 steps, the team members self-identified that a whopping 59 percent were waste.

This recognition became the inspiration to design a deliberate and focused process that was almost entirely value added from our patient’s perspective. Gone were actions such as duplicate instances of querying the patient for go home information—quintessential over processing. Instead, the team centralized communications so everyone had access to the most recent patient-provided data. But more importantly, the exercise of working directly with the patient and analyzing their actions alongside him—looking through his lens—shifted their thinking and their view point. At the end of the week, we had a whole team of waste watchers.

Ken Eakin (Senior Advisor, Operational Excellence, Export Development Canada)

As a financial services company, what we “produce” is basically data, decisions and knowledge, stored in human brains and information systems. If you were to go to the gemba in my office and stand in one fixed spot, like Taiichi Ohno famously did, you’d just see people sitting at their desks staring at monitors and tapping on keyboards. Or you’d see them in meeting rooms, talking. You wouldn’t see any finished product waiting to be shipped or excess inventory piling up. So the most frustrating source of waste in my field of work—to borrow the words of Shigeo Shingo—is the waste that we cannot see.

As a financial services company, what we “produce” is basically data, decisions and knowledge, stored in human brains and information systems. If you were to go to the gemba in my office and stand in one fixed spot, like Taiichi Ohno famously did, you’d just see people sitting at their desks staring at monitors and tapping on keyboards. Or you’d see them in meeting rooms, talking. You wouldn’t see any finished product waiting to be shipped or excess inventory piling up. So the most frustrating source of waste in my field of work—to borrow the words of Shigeo Shingo—is the waste that we cannot see.

While workflow “invisibility” is not a classic form of waste, it’s at the root of our long hours and chronic lack of capacity. The busier we get, the more “heads down” we get, focusing on what we need to do right now to complete our work faster. This makes us blind to how our work affects others working downstream from us. We push work on to them without much thought to how this might be creating systemic bottlenecks and overwork throughout the company.

So what are we doing about it? Almost all teams in my office use some form of visual management to track their work, and the most productive amongst them are closely managing and adjusting the volume, duration, and sequencing of their work on a daily basis (Jim Benson’s Personal Kanban approach is a simple yet effective tool for office environments). A few teams have implemented rigorous standard work, cross-training and work-sharing systems, with really impressive capacity gains. Persistent and patient leadership has been crucial to making this all happen.

Like most companies, we are organized structurally in vertical silos, but our customers experience value horizontally. As our lean journey continues, our next big challenge is to expand the improvements we’ve made at the team level to our enterprise-wide value streams. And it will all start by seeing the work—and the waste—clearly.

John McCullough (Operations Manager, Crayola)

I have found the highest level of frustration is due to waiting, specifically when it comes to tough problems. When a problem is identified that would be difficult or impossible for the identifier to work on themselves or with their team, and must wait until the problem is communicated, dispositioned and hopefully worked on by someone else, it’s easy for frustration to ensue.

Difficult problems that people are either not empowered to or not capable of working on are the most frustrating, because it makes people feel helpless. While they wait with hope, sometimes even just for a ‘yes/no’ response, they can begin to feel victimized. Sometimes they become so focused on those problems that they overlook the many problems that they can work on.

I find the best way to avoid this is to empower people by expanding skill sets and giving them the freedom/authority to reduce or eliminate problems that were previously “untouchable.” I also realize there are often roadblocks to making that a reality. The next best thing, which is also easier to implement, is to have communication, escalation and decision-making processes that are fast, specific, standardized and executed with rigor. It is also important that, when problems really are too big for the identifier to work on, we redirect said person to problems that they can work on.