At the beginning of my fourth year in medical school at the University of Michigan, I was given the opportunity to lead a quality improvement project that would address the growing opioid epidemic in the state of Michigan. Specifically, I’d be partnering with the newly-established Michigan Opioid Prescribing and Engagement Network (M-OPEN) to find a way to prevent excess pills from entering our community. Diversion of excess opioid painkillers is a major driver of misuse and abuse, with 70 percent of individuals who use opioids non-medically obtaining the medication from a friend or relative. What’s more, since 50 percent of the opioids in Michigan enter the community after surgery, we decided to focus on post-operative prescribing.

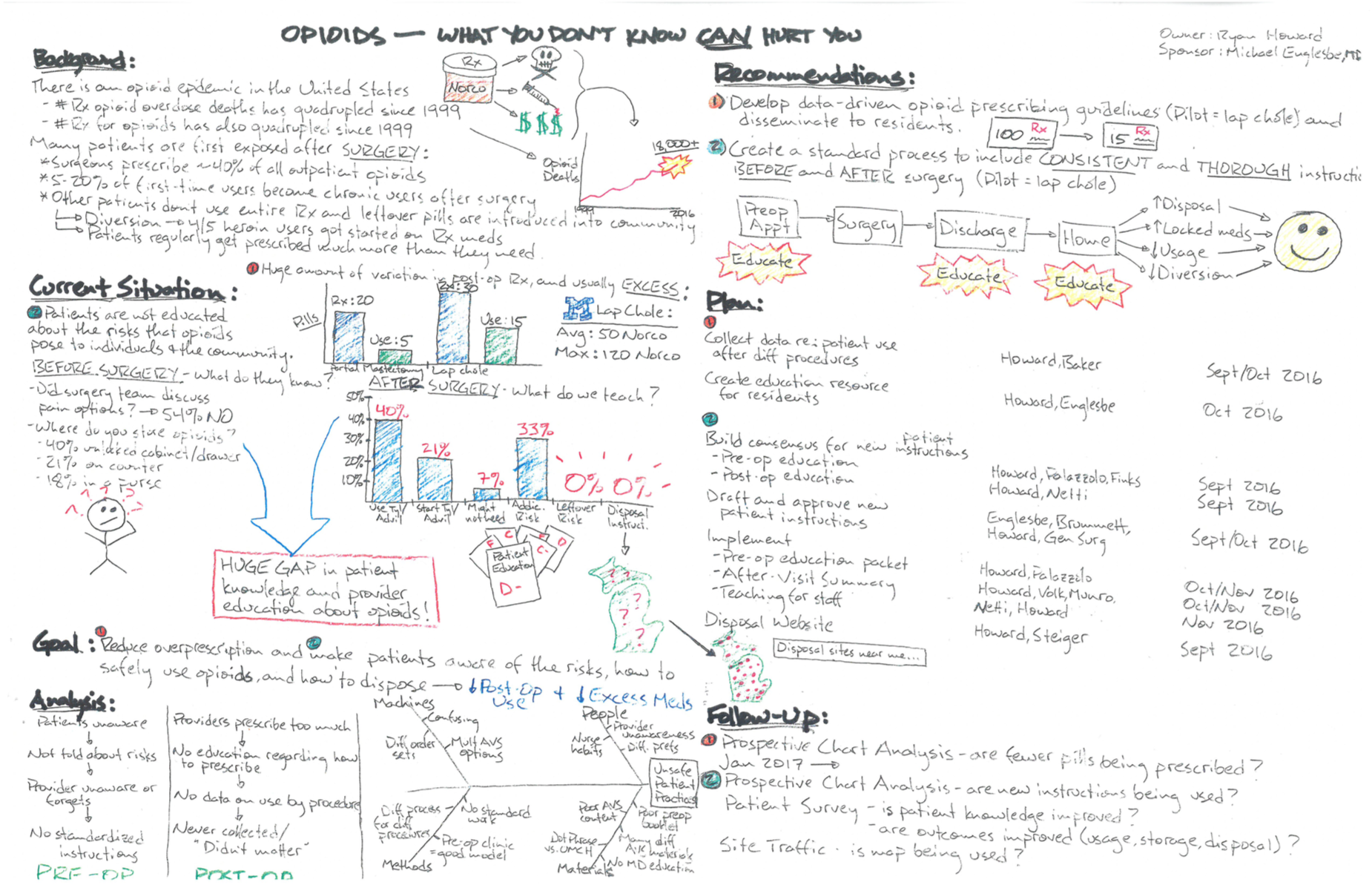

At the outset, we picked a common, generalizable surgical procedure (gallbladder removal) and looked at how many narcotic pills were typically prescribed to patients. What we found was a tremendous amount of variation. Some patients were walking out with as few as 12 pills and some with as many as 100. Root cause analysis helped us hone in on the problem: Why was there so much variation? Because there were no standard prescribing guidelines. Why no guidelines? Because they had never been developed. Why? Because nobody had ever looked at how much pain medication patients typically needed. Why? Because giving more than enough wasn’t considered a problem.

So we began surveying patients on how much pain medication they needed after this surgery, and found that half of patients used five pills or less. This was shocking to say the least – patients were going home with upwards of 100 pills and taking only five. What’s more, we found that 70 percent of patients did not dispose of leftover pills. As a result, we developed prescribing guidelines that were more consistent with what patients actually needed, not just what we thought they needed.

We also wanted to improve patient education regarding pain after surgery. This part of the project relied heavily on gemba. I spent a good portion of my time literally sitting in on clinic visits or watching nurses discharge patients after surgery. The information gained here was invaluable. For example, patients often did not know that they should dispose of leftover medication; if they did ask about disposal, nurses did not have a good resource to tell patients where to take leftover pills. Therefore, we created an online map where patients can now search for opioid disposal sites near their home address. It can be found at http://umhealth.me/takebackmap.

Value stream mapping the patient’s journey of getting gallbladder surgery allowed us to identify all of the stakeholders that would have to be involved if our new guidelines were to be successful. So we made sure to meet and speak with providers in the preoperative clinic, the faculty and residents who performed the actual surgery and wrote the prescriptions, and nursing staff who discharged and followed-up with patients after surgery.

To prepare for piloting our guidelines, I compiled all of the information on the background of our issue, the root cause analysis, and the owners of each area of implementation into an A3. As a student who had never created an A3 before, I found this process incredibly helpful. Not only did it help me organize my plan for conducting this project, but it provided me with a communication tool to use when meeting with staff to implement our new prescribing guidelines. What’s more, as others made contributions, we were able to improve our project in ways we hadn’t anticipated.

In just the first month since implementing our prescribing guidelines, prescription sizes following gallbladder surgery have decreased by more than half. This means that compared to historic prescription sizes, we have prevented roughly one thousand pills from entering the community. Despite dramatically reducing prescription size, there has been no increase in calls for refills. We hope that by continuing this work and expanding it to other procedures, the number of pills kept out of our communities will grow exponentially.

How has lean helped you tackle a problem bigger than your organization?