Dear Gemba Coach,

Surely a step forward in a lean transformation is a good thing, even if it’s not completely in the right direction?

Well, any step is a good step if we learn from it. Otherwise it’s just as step – and a step in the wrong direction does take you downhill. The whole point of PDCA is not just “plan” (the direction we want to go) and “do” (the step forward) but also “check” (is this going as we intended?) and “act” (what conclusions do we draw?). Moving forward for moving’s sake is actually no step at all.

Increased output doesn’t necessarily yield outcome. This is socially difficult as people just want to move on, to do stuff, to get cracking. But the odds are that easy steps are steps along the path of least resistance (although they might not feel so easy to the person who actually gets the job done). Similarly, steps in the right direction tend to be an uphill struggle, and not so easy.

Think about quality issues. Think of any process where you are delivering late because of uncertain quality. The path of least resistance is to increase output and inspect and sort the work more thoroughly. In doing so, although your yield diminishes (proportion of good work to done work), your delivery output actually increases (less unhappy customers). BUT, your learning opportunities and the probability of ever solving the fundamental problems recedes badly.

On the other hand, trying to identify the point of cause, the root cause and come up with a real countermeasure is hard and requires inquisitiveness and creative thinking – meanwhile, customers are not getting the jobs they asked for. This is hard. Following the first option is not necessarily incompatible with the second as long as the “check” (what happens to first-time-through?) is done properly, leading to the right “act” of distinguishing stop gap measures from policies.

Watch Your Steps

The problem is tough enough with routine work, but imagine product design issues or marketing branding problems. In many situations, knowing what “the right direction is” is not obvious in the first place. How many product redesigns have we seen where the engineers are really happy with what they’ve done, but customers don’t take to it (New Coke anyone?) or rebranding gone bad (remember the Gap’s new logo until they retracted and returned to the old one?). The engineers and designers who make such costly mistakes are convinced they’re doing good (hard to judge your own lack of talent and/or inspiration) but, still …

Steps forward are steps forward only if they go in the right direction. The question often is, what is the right direction? Thankfully, lean has some very specific pointers to help us with this.

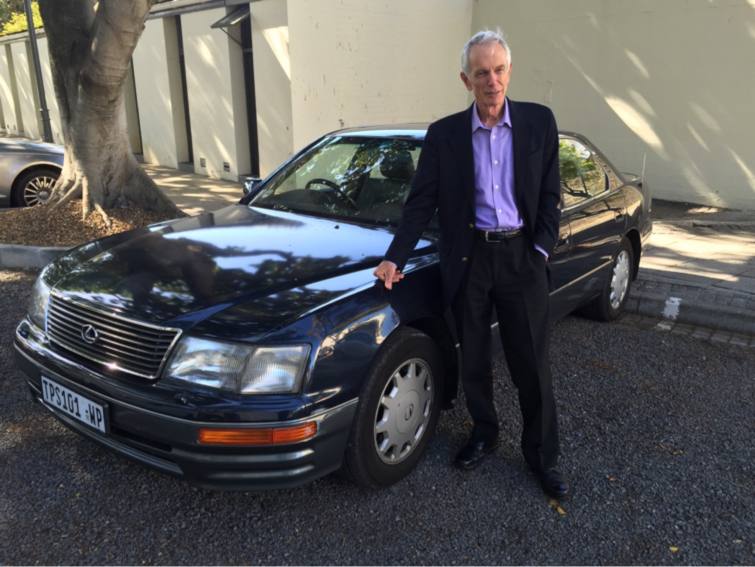

First, stand on the shoulders of giants: Don’t go off into the blue by yourself. Choose the best competitor in your area, or the best product, or design, and emulate. This doesn’t mean copy blindly, but try to so as to understand the underlying choices. When Toyota designed its first Lexus, it wanted to achieve the drive of a BMW with the comfort of a Cadillac. So, sure, Lexus number one looked like a botched Mercedes, but it still had an astounding success because engineers put their energy in solving usage problems rather than reinventing luxury cars in the abstract. The result was a luxury brand and car that many – like African Lean Institute Founder Norman Faull, below, with his beloved Lexus – consider to be the best.

Second, iterate: Understand the flow of products you’re stepping into and have a clear vision of:

- Performance: the functions the product promises to deliver

- Quality: whether the product actually delivers on its promises

- Cost: for how much?

Looking at a flow of products usually means that some technical aspects can remain standard while some others need a lot of work. The main point is to be very careful with architectural changes which could radically change how customers relate with the product without the designers ever realizing it at first.

Thirdly, hansei: Accept that no mother finds her baby ugly, which is why it’s essential to think of the next step right at the end of the redesign (or simple kaizen). Thinking of the next kaizen will lead you to evaluate more clearly the one you’ve just made (yes, confirmation bias and all) and prepare you mentally to consider that maybe your great step forward wasn’t so great anyway.

Hard Questions

There are three overarching lessons in lean thinking implicit in your question:

- Lean thinking remains challenging, always: Nobody likes to hear that their efforts are not helping, particularly when they’ve worked hard at it, but “problems first.” The moment people refuse to be challenged on “why?” and only want validation of what, you’re in much deeper trouble than you think. Lean is challenging. That’s one of its key merits (and something of a drag as we’d much rather be friends with everyone all the time).

- Kaizen means repetitive experiments, not try it once and move on: Experiments are planned activities for the purpose of learning. Too often, people start an “experiment,” hit a snag, call it a failure and … go and try something else elsewhere. True kaizen will occur when the people themselves have finally found how to solve a technical process which will deliver more value to customers. Kaizen is more often than not (unless we’re very lucky or there are low-hanging fruits) the result of repeated attempts at solving the problem, not one lucky throw.

- Clear direction is essential to kaizen: Without a clear direction showing which way we want to go, what is a valid solution versus what is not, people get easily lost in doing, and as a result, although they can’t see it in the fog-of-war, find themselves following the path of least resistance into the valley of mediocrity – and no competitive advantage (Haven’t you noticed that all websites now look the same?)

Yes, a step forward can be a bad thing, because it can take you a step further away from your goal. Yes, it’s easy to tell people “well done” because they have moved and you don’t want to put them down, and block their creativity – they might never try anything new again. Yes, this is a conundrum that is only solved by a rigorous culture of plan-do-check-act without which you can be performing kaizen “experiments” until the cows come home, and still drift down to exactly where you don’t want to be – with people committed to their own ideas on top of it.

Years ago, senseis used to look at kaizen efforts with a sensei-like frown and ask the hard questions:

- What was the problem you were trying to solve? (Yes, I can see you’ve implemented kanban, I’ve seen kanban systems before, but what was the problem you were trying to solve?)

- What specific technical point have you learned in doing this? (How does that either bring more value to customers of make the operator’s job easier?)

- Who did you work with to come up with this and what do they think of it? (And what have they learned?)

Such questions perfectly reflect the thinking behing the Lean Transformation Framework. Never easy, but so much more deeper thinking!