This is the second of two articles exploring why and how to use the five principles of lean thinking to address systemic racism. Read part one here.

**********

As the lean community works to move from firefighting individual workplace incidents of prejudice against or hostility toward people of color, we need to examine the big picture and focus on the system, or in lean vernacular, the Value Stream, to drive long-term transformation of the entire enterprise. To do so, consider each of the five principles of lean thinking through the lens of antiracism.

Lean thinking leaders must be relentless about eliminating waste. They must also be very clear about which aspects of the business add value to the customer and which do not. Value is created by employees serving customers with desired products and/or services. Leaders need to see the value that Black people and other people of color bring to the table, which includes different, important, and competitively relevant knowledge and perspectives about how to actually do work — how to design processes, reach goals, frame tasks, communicate ideas, and lead effective teams (Thomas & Ely, 1996).

According to Debby Irving, author of Waking Up White, when this multicultural value is nurtured, it expands everyone’s ability to innovate and solve problems. People of color, by necessity, have operated across two cultures — the dominant white culture and their own minority culture, including sometimes using different languages. This equips them with unique strategies to cope with cross-cultural challenges, developing their flexibility, adaptability, open-mindedness, and resilience — all qualities necessary for solving problems and innovating in an ever-changing, fast-paced, globally connected society. This value is not to be concealed or diminished by assimilation or viewed as flaws or deficiencies because it is different; it should be recognized as strengths and assets. Systemic racism not only squanders this value and minimizes the potential of marginalized groups, but also obstructs the opportunities for mutual learning and connection between whites and innovative problem-solvers of color.

From an anti-racist perspective, policies, systems, and practices that produce and normalize racial equity are value-added. Those that create and sustain racial inequity between racial groups are nonvalue-added or waste. As Kendi states, there is no such thing as a non-racist or race-neutral policy. He reasons that every policy in every institution in every community in every nation will result in one of two outcomes: continued racial inequity or equity between racial groups. The role of a leader is to seek the kind of self-introspection needed to:

- Cultivate anti-racist leadership skills.

- Seek guidance from diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) experts.

- Develop subordinates so they can speak up when they see discrimination or microaggression.

- Grow and improve as allies.

- Remove obstacles and set challenges and goals so that teams at all levels of the organization can contribute to their company’s continuous improvement.

- Commit to combatting racial, gender, and other forms of discrimination, and attainment of its long-term anti-racist goals.

Value Stream

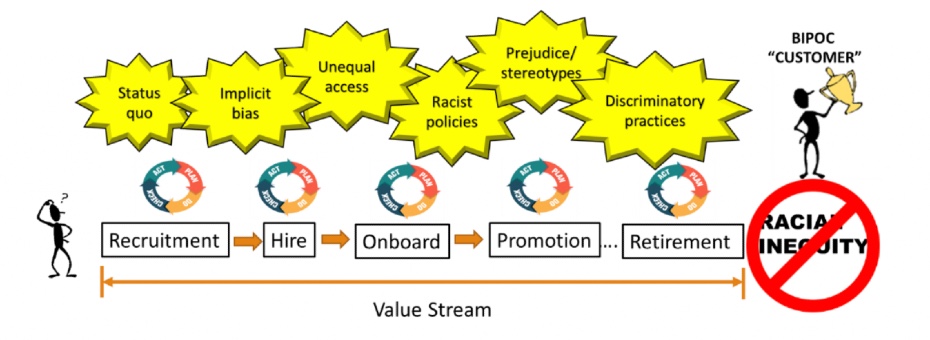

The value stream is the flow of activities and work processes that produce value for a customer. In the context of an organization’s people (internal customers), a value stream encompasses all the processes employees will encounter from the time they are hired until they leave the organization. These processes include policies, systems, and practices surrounding how employees are recruited, hired, on-boarded, trained, managed, compensated, reviewed, communicated with, and given opportunities for promotion. According to a Lean Enterprise Institute faculty member, these kinds of policies, systems, and practices must be examined closely to determine whether they enable or hinder the adoption of a team-based, collaborative, problem-solving culture. For an anti-racist organization, this examination should also include whether policies and/or processes hinder the recruiting, hiring, developing, and promoting of people of color. The lean approach is to create systems and policies that ensure equity and trust among workers to create an environment in which every team member is willing not only to see and report discrimination, but also to actively engage in solving it.

Flow

Flow, with anti-racism in mind, is defined as the progressive achievement of all the critical processes along the value stream so that Blacks and other people of color proceed from recruitment to retirement without discrimination, racist policies, or inequity. Leaders need to assess the demographic makeup of the entire staff, at all levels and wage scales. A lack of diverse racial and ethnic representation (Black, Latinx, Native American, and Asian) at your organization indicates the waste of racism within your recruiting and hiring practices. Closer examination of the language used in performance evaluations may also reveal internal biases that impact pay and promotions. Leaders need to commit to a strategic plan that centers on anti-racism, racial equity and healing, and designing long-term action plans to develop and retain Black talent. They must examine the interview process, performance management practices, compensation structures, and retention and promotion policies to understand how these processes are failing your Black staff. Ask yourself, who among the talent of color can be mentored and sponsored to ensure that they are supported at each stage of the value stream? Does everyone have the opportunity to reach their fullest potential within your organization?

Pull

Generally speaking, if people of color cannot yet flow through a value stream like their white colleagues without being disrupted by discrimination or racist policies, then a pull system might be implemented to address some of these barriers. For example, at Toyota, a worker encountering a defect on the assembly line and would pull an andon cord to trigger support personnel to come to do some immediate and preliminary problem-solving. Similarly, when a Black employee is victimized by a discriminatory policy and/or actions, a pull system could activate a quick response Employee Resource Group (ERG). The ERG, staffed with cross-functional/cultural team members with lean problem-solving skills, including a DEI change agent with senior management sponsorship, would offer support and confront the key issues, identify root causes, and brainstorm and implement countermeasures. Problems like microaggressions or a racist joke might require a “quick fix.” More complex issues like a toxic workplace culture, fears of retaliation, and other barriers that prevent clear pathways to career growth and promotions, may require rapid improvement events (RIEs). The pull system is set up to respond to actual real-time needs rather than waiting weeks and months for complaints to stack up and fester, or worse, go unaddressed causing talent of color to prematurely exit the organization.

Perfection is defined as the complete elimination of waste so that all activities along a value stream create value. The ultimate goal of a lean approach to systemic racism would aim for zero racist policies, zero racial discrimination, and zero racial inequity. Anti-racist leaders have zero tolerance for patterns of dominance and subordination based on the presumed superiority and entitlement of some groups over others. They root out barriers that block employees from using the full range of their competencies, cultural or otherwise. Like striving to achieve zero defects or zero accidents, zero racism is never-ending work that leaders must commit to each and every day. All parts of the value stream have to be examined and “kaizened” over time to support the anti-racist culture that organizations and leadership seek.

The Bottom Line

Systemic racism is not just a problem confronting Black people and other people of color; all people function better in waste-free environments, and racism is a corrosive form of waste. It is imperative that our lean focus on the traditional forms of wastes (transportation, inventory, motion, waiting, overproduction, processing, unused talent, and defects) expand to tackle systemic racism. We will need to resist the urge to quickly put racism in the category of unused talent because its root causes are not necessarily the same as other causes of underuse of talent. Addressing systemic racism requires DEI insights and expertise to effectively dismantle. In addition to being socially responsible and making the most of the problem-solving capabilities and creativity of people of color, it makes good business sense. According to a study by diversity expert, Cedric Herring, “Companies reporting the highest levels of racial diversity brought in nearly 15 times more sales revenue on average than those with the lowest levels of racial diversity.” And McKinsey & Company found that “companies in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity are 35% more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians.”

A Call to Action

Programs designed to address systemic racism and increase diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace often fail. To create anti-racist organizations to fit, value, and respect all people, leaders should step forward with a sound vision framed by the five principles of lean. This is critical to set the proper strategic direction for the company, make anti-racism a top priority, and ensure that resources are being committed appropriately. Expect conflict and resistance, as it is par for the course for transformation to occur and be sustained. Do not try to avoid it. Instead, view it as an integral part of the transformation process. Leaders must stay the course, create safe and brave spaces to problem-solve, and use their power, platforms, and resources to dismantle institutional barriers to the success of people of color. Doing so will help communities overcome systemic racism, unleash suppressed talent that has been undervalued and mostly untapped, and build a better world for all of us. The five lean principles will guide us on this path forward. However, we first need to answer the question, “Are you willing to join others in the arena to get in good trouble to dismantle the insidious waste of systemic racism?”

References:

- Jonathan Bundy, As Companies try to Address Racism, a Generic Response is No Longer Enough, Fast Company, August 3, 2020

- Mark Graban, Podcast #378 – Christopher D. Chapman and Valeria Sinclair-Chapman, PhD on Lean, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Mark Graban’s Lean Blog, July 31, 2020

- Alex Berezow, Coronavirus: Covid Deaths in US by Age, Race, American Council on Science and Health, June 23, 2020

- Laura Morgan Roberts, Ella F. Washington, US Businesses Must Take Meaningful Action Against Racism, Harvard Business Review, June 1, 2020

- Pooja Jain-Link, Julia Taylor Kennedy, & Trudy Bourgeois, 5 Strategies for Creating an Inclusive Workplace, Harvard Business Review, January 13, 202096

- Time’s Up Guide to Equity and Inclusion During Crisis: Building an Anti-Racist Workplace, 2020 Time’s Up Foundation

- Ibram X. Kendi, How to be an Antiracist, Penguin Random House LLC, 2019

- Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility, Beacon Press, 2018

- Paul Gompers, Silpa Kovvali, The Other Diversity Dividend, Harvard Business Review, July-August 2018

- Joe Murli, Human Resources and Lean; It Really is about People, The Lean Post, March 8, 2018

- Vivian Hunt, Dennis Layton, & Sara Prince, Why Diversity Matters, McKinsey & Company, January 1, 2015

- Debby Irving, Waking Up White and Finding Myself in the Story of Race, Elephant Room Press, 2014

- Jeffrey K. Liker & Gary L. Convis, The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership, The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2012

- Cedric Herring, Does Diversity Pay?: Race, Gender, and the Business Case for Diversity, American Sociological Review, 2009

- Jeffrey K. Liker, The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer, McGraw-Hill, 2004

- David A. Thomas, Robin J. Ely, Making Differences Matter: A New Paradigm for Managing Diversity, Harvard Business Review, September-October 1996