Are you managing “by the numbers”? And more importantly, if you are, are you using the right metrics to gauge your productivity? I think most people understand the concept of managing by the numbers, which usually means that their boss shares targets and they then do whatever necessary to hit “the numbers” especially those tied to performance evaluation, bonus, wage increase, or promotion. I am always amazed when I see this in organizations (which is a frequent condition): people find a way to meet their targets because it’s simply human nature to be result driven. The problem lies when we are asked to sift the sand to see if there is any gold there—most often there isn’t. In other words, a better question than “did you make the numbers?” might be: “what are the most important metrics you should pursue?”

I was hired at TMMK before we were able to sell the vehicles we produced. This gave me the opportunity to see how all the components (of TPS thinking) came together to determine how we measured how efficient we were in our processes; while bringing the waste to the surface in order to improve and meet customer need. I learned that doing business this way meant that we couldn’t mask problems very easily.

My trainers helped me to see how tracking certain key metrics helped understand what the customer needs from our organization (internal and external), and how well each process works to meet that.

My trainers helped me to see how tracking certain key metrics helped understand what the customer needs from our organization (internal and external), and how well each process works to meet that. We started by focusing on our “takt time” (a German not Japanese term). We needed to know how fast the customer was pulling from us (this can be any service, output or product). Determining this number invariably involves other departments (silos) within the organization like sales, purchasing, engineering, human resources, R&D, and suppliers. The process of figuring this out is often as rewarded as it is challenging. It certainly took discipline and accountability from our leadership. I encourage folks to work diligently to create an “us”- not a “we and they” atmosphere!

In our case we determined takt from the previous three-month average pull. This dialed us in to the customer and helped us understand what we were capable of regarding other key components such as machine or process capacity (cycle time). If you aren’t capable of meeting what the customer needs when they want it, consider it a red flag. Alas, most organizations can’t tell you this much– they just run wide open and stockpile inventory, which looks really good on paper if that’s what you measure.

It’s important for your organization to be able to differentiate cycle time and takt time. Cycle is what it takes for your process to meet the takt time (determined by customer demand). The two measures do not necessarily have to be the same, based on certain factors (leveling, mold or equipment changes). In my experience working in the plastics department we had factored in mold change time so our cycle time was actually faster than takt time to accommodate for “planned” downtime (of course always trying to minimize that time). It’s also crucial to perform production capacity studies for each process (manpower/equipment/machinery). Again, you must know production capability to recognize gaps to the customer need. (Please note the difference between total capacity; meaning I can just run the equipment 24/7 (if you are running to total capacity as the norm then common sense will tell you there will be problems meeting customer need), versus process capacity which can be a normal working day time requirement.)

If you were to create an ideal state you would want to know what your customer pull is, and then purchase the specific equipment that meets that need (cycle). Keep in mind however that even if I meet the ideal state today, tomorrow that may change. Built in to our production system at Toyota was the ability to adjust when the customer demand changed either way. We had to build in flexibility in our processes in order to remain competitive and not pass cost onto the customer. We did this by always understanding takt, cycle, capacity and manpower for every process.

While most do not have that luxury of knowing the answers to all the questions above, they represent a vital starting point for anyone starting their Lean journey. These measure help an organization grasp the current state and understand how to identify waste, see ways to embed kaizen in those areas, and explore what other options are possible to effectively meet the customer (manpower, equipment upgrades, or outsourcing to name a couple). If this is the journey you are going down then it’s important to have leadership on board.

Once the takt, and process capacity are understood then it’s time to develop standardized work to assist in determining the manpower necessary for production needs. Each process knowing its capability must have standard work that involves specific steps with times to complete the cycle time. After these are developed, then Job Breakdown sheets are created for the key points and reasons. This allows each person to use Job Instruction training (JIT/TWI) to fully understand expectations so they can see abnormality at a glance and recognize potential improvements as they work the process every day.

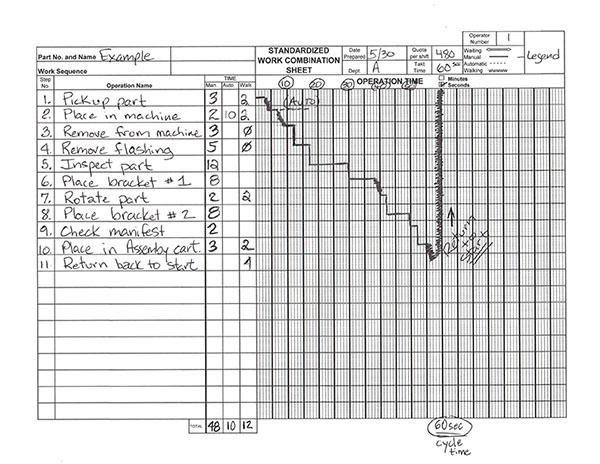

We used a work combination table (example below)

as the tool to help visualize the cycle time, equipment involved and standardized work. We referred to this board to see what the machine was doing and when, what the worker was doing and how much time per step, along with any walk time (even wait time) involved to fully visualize the complete cycle. We all shared this as the benchmark for future kaizen. This was done for all processes that created outputs. When you think about it, how you can do business effectively, sustain this for the long-term, and be flexible without understanding these key components? Without clear and simple metrics like this you can never measure how you are doing based on the customer’s expectation, and be flexible to their ever-changing needs.

So what does all this mean?

Organizations and the individuals within should know where they stand compared to the standard on an hourly /daily basis in order to make any meaningful improvements. In my experience we used “plan versus actual” boards for each process which visualized this information each hour, factoring in downtime we had that could have been equipment related, (such as training related activities, or andon pulls, etc.) We also tracked a variable called “wait Kanban”: the assembly shop we were providing parts for had downtime which in turn didn’t allow them to return their carts (kanbans) for replenishment (pull system), so instead of continuing to run and “stack” parts, we stopped. This time was not calculated as downtime, but as “wait kanban”, which didn’t count against our production efficiency. These activities were important to our work, and necessary to include so that we could extrapolate all this information.

After our shift every day we were responsible for a daily report to calculate the productivity for our group which contributed to a department need; which supported the plant need. This report factored in our capability, our run time, downtime, repair, scrap, delay work, wait kanban, and supplier/vendor shortages. This gave us our daily “parts per hour” efficiency rate, which we based on the expectation which gave us our productivity rate for the day.

We knew every day where we fell short of the standard and used PDCA to avoid replicating the same problems every day. This was considered grasping the problem situation, or the first step of problem solving.

If a person doesn’t understand daily expectations based on takt time, cycle time, production capabilities, and standardized work then they are just haphazardly running till the next shift comes in to take over (vicious cycle). Every day we managed to the customer need, and not to a random number pulled from a hat that met an objective that might have looked good on paper short term. This approach marked the beginning of our leaning a new way of thinking. If a person doesn’t understand daily expectations based on takt time, cycle time, production capabilities, and standardized work then they are just haphazardly running till the next shift comes in to take over (vicious cycle). They are doing work that is not sustainable for long-term growth, nor are they developing the capability to understand how to improve. Although I’m describing a manufacturing setting this thinking can be applied in any industry where services or outputs are created and a customer has an expectation.