After Art’s detailed look at the Tuckman model, it can be intimidating to look at all four parts of the model accurately. Thankfully, Art’s target for this week is on the storming phase, lending a technique that will assist in your problem-solving journey. Find a lightly edited transcript below.

Part six of eight. Watch the others:

Part one, Coaching Problem-Solving

Part two, Lessons from NBA Coaches

Part three, Lessons from Martial Arts

Part four, Military Science and Leadership

Part five, Tuckman’s Model of Team Formation

Part seven, Dreyfus Model and the Stages of Learning

Part eight, Toyota Coaching Practices

Hi everyone. This is Art Smalley, president of Art of Lean, Incorporated. Today, in conjunction with Lean Enterprise Institute, I have another video for you today, this time, continuing on our theme of problem-solving, coaching, and ways to shorten that lead time to getting results. Now, the previous video, we talked about different models and how we often get any storming phases, and I want to offer one suggestion or one technique that sometimes helps you get out of that. So if you’re interested in that topic, stick around, I think you’ll like it.

Looking at the Storming Phase

Now in a previous video, we talked about the Tuckman model of team transformation, and in his depiction of events, what happens as team forms, there’s a little bit of a happy period, and then they get into a period of dissatisfaction and storming agendas come out, people argue, power struggles, and things are up like that. Eventually they worked their way out of that norm and find behaviors, standards, and things they can wait at, collaborate and work together better and function as a team, and you get to the highest level of performance sometime after that. And like Toyota had a model of that too, what I called the D-Zone, C-Zone, B-Zone, A-Zone.

But many of you have been in this situation. Here are some pictures, graphics, just things I picked off the internet. I bet you’ve been in a problem-solving meeting or improvement activity where you felt like this, right? Somebody’s got out the bullhorn, shouting their way of doing things, and some people are lower counter punching high or somebody saying, “No thank you.” People are pulling and not in the same direction, people are thinking things in their head and in disagreement, and then sometimes there’s a team A and a team B, and they just line up on different sides of the table and go at it. And that’s the reality of putting teams together and working whether it’s sports, or problem-solving, or anything. This occurs and a good coach has to have ways of managing and thinking about it.

So, I mentioned in the previous video that the old Toyota coaching guide for problem-solving and QC activities, and there was the X and Y-axis, and the Y-axis deals more about this part, about the subjective side, the emotional side, things you have to do and realize that people have different personalities, perceptions of the problem. That’s not necessarily negative or evil, it’s just, we look at the problem differently sometimes. Different social styles come into effect, different behavioral styles, different learning styles, all contribute to unintended consequences of storming or not getting along at points in time. And look, the way through this to me is actually being a good virtuous person. When you’re a coach, you got to practice putting virtue into the team, virtue in your actions and a variety of ways. It’s not one thing, it’s not one simple thing, but you got to practice the integrity, the respect, the courage, the honor, the compassion, the honesty, the loyalty, all of these things have to come into play if you’re going to be a good teammate, a good coach, and get people to trust each other and work well with each other.

When you’re a coach, you got to practice putting virtue into the team, virtue in your actions and a variety of ways.

Now, every situation is different. I wish I had a canned answer for you. I could just say, “Ask this question” and magically, it goes away. It’s never that easy in real life. I think that survey tools can often be useful. There’s a variety. I can’t go into all of them today, but most of you are probably familiar with at least one of them. There’s the Myers Briggs personality test, the Disc Profiles one, there’s the Big Five personality traits, which is very more common in academia and published literature. There’s something less familiar called the Kolb Learning Styles, which I’m going to talk a bit about today, because it lines up very well often with problem-solving storming, there are other types of storms that occur, each of these has a role, a time, and a place, but when it’s problem-solving storming, one of these for me has been a little more useful than the others.

Kolb Learning Styles Indicator

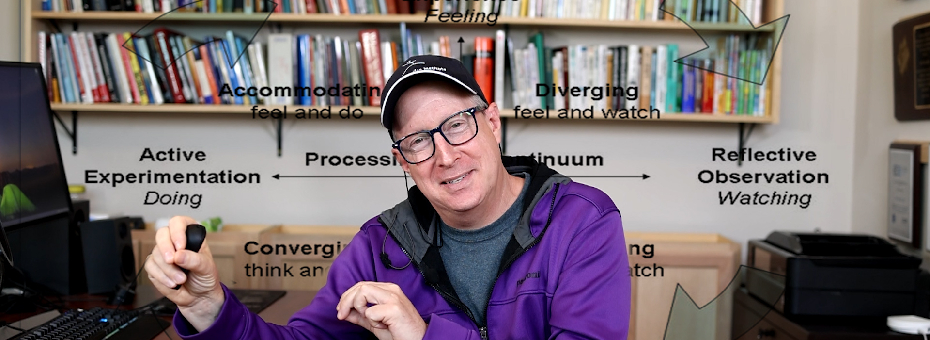

It’s also less well known, so let me just talk about it. It’s called the Kolb Learning Styles Indicator, of course, there’s a research Institute, a professor and wife team behind it, David and Alice Kolb. And you have to pay to take the survey, it’s copyrighted and all that good stuff, but it boils down to this, you will answer a series of questions and your answers will be put into a matrix of quadrants. And at one quadrant, it finds out if you steer towards enjoying the concrete experience, the actual world, and that’s very good for problem-solving. In Toyota, for example, we use the Gen word a lot, Genba, Genchi, Genbutsu. That all indicates a preference, if you like those words for actual objects, actual things.

The opposite of the concrete experience on that vertical axis is the bottom part, which is people who exhibit a preference for theory, abstract conceptualization, theory and thinking. So these people like scientific theories, they like to be in the realm of ideas, numbers, and data. They say, “Let’s go to the shop floor,” but they tend to be in their office a lot more or teaching in the classroom for example, and that’s fine. Toyota production system is a thinking system as well, that the T down at the bottom abstract, conceptualization, thinking and planning really matters.

The horizontal axis is called the processing continuum and shows whether you have a preference for active experimentation, the doing side of things. Look, you got to learn by doing a lot of the time, there’s no substitute. The opposite of learning by doing is more than learning by reflecting, observing, and reflecting over a longer period of time. And look, both of these are TPS, Lean thinking as well. Learning by doing is one side quickly, the opposite is slower, reflective thinking, and thinking. We use the word Hansei a lot in Japanese, that’s a slower reflective form. So I can put TPS and Lean buzzwords in all of these quadrants, and good thinking styles need to embrace them at different points in time. But here’s what happened, back to my storming phase, the Tuckman model of storming and the low point when people are storming and problem-solving.

So to make this clear, I’m talking about a type two problem-solving, which has a defined problem eventually, but an unknown solution space. The root cause by definition is unknown in type two. You’re going to have to go on a learning journey to explore it and find it as quickly as possible. If people score in the quadrant, which is between a concrete experience and active experimentation, they’re the ‘Just do it’ crowd. They come to the meeting, but they already know the answer. “Let’s do this. Let’s not waste time in training, let’s not waste time in meetings.” 30 minutes is all they can stand in the meeting, maybe an hour and then, “Let’s go out and do it.” They’re ready to charge out the doors and go and do it. They problem-solve by bullet list. They have a list of action items and you just go and do it.

Sometimes for easier problems, what I call type one or cleanup activities, is that that is absolutely fine. But not always. What I call the type two problems of deeper complexity, unknown root causes, beyond the fishbone, beyond the five why, where you actually have to measure things with facts and data, a little more rigorously. They don’t do well. The Bottom right-hand quadrant, the people who score between reflective observation and abstract conceptualization, the thinkers, they really do well on those types of problems. They want to collect data. If you give them two weeks to solve a problem, after two weeks, they’re still designing the format, the template, the check sheet, and getting very good data. But they’re going to nail it in the long run, but they’re not very fast at doing it. Those are the people who are really into statistics and measurement. They understand theory of variation, they understand common cause, special cause variation. They actually do statistics. They’re the DMAIC people who actually do statistics, that measure things well.

Look, there’s a strong point for that. There’s also a weakness if you need a today’s solution. In between those two, there is the active experimentation and there is abstract conceptualization quadrant. These are the process thinkers, and what they want to do is quickly slap a framework on everything. They cut and paste well, they use PowerPoint slides to problem-solve, they’ll say, let’s make an A3 report, and that’s fine. That’s, that’s TPS, that’s lean thinking as well. But they’re always pushing their framework. The answer is the framework, the answer is the process. Do my PDCA, do my OODA loop, do my DMAIC framework. But the people in this quadrant usually don’t use statistics or data. They quote a lot of things like science and data, but they tend to do a Kaizen event and go 80/20 in a very pragmatic. Again, there’s a time and a place for that, it works well. But they storm with the opposite quadrant. You always storm with your quadrant and the opposite.

Different Strengths, Different Quadrants

There’s a picture thinker, strategy quadrant. They lack concrete experience and reflective observation, but they don’t converge to the narrow, they diverged to the bigger picture. So people like Steven Jobs were like this, obviously, always thinking, “What’s next? What’s the big picture? What’s the big thing? What’s the strategy? What’s the bigger issue in innovation at play?” The strategy people in that quadrant looked down at the process thinkers as people tinkering around with the deck chairs on the Titanic, you’re just doing something while the bigger ship sinks. And look, there are strengths and weaknesses to all of these. This is not a right or wrong. The ‘Just do it’ crowd has a point when it’s doing certain types of simpler problems or activities quickly, the measuring crowd has a point on the harder problems where variation and unknown root causes are involved, and measurement has absolutely got to come to the forefront.

Process people have a good point. You better have a process and way to follow and things to do, so you’d have a good sequence. And the bigger picture, the divergers in the upper right-hand quadrant, they’re right in the long run, if you don’t have a strategy, new product innovation, you’re not going to exist very long as a company. But you have to learn from each other, in problem-solving these strengths and weaknesses, come out, your personalities and behaviors on top of it, magnify the situation. And the point is eventually you need to have the language and vocabulary to work together, see each other’s strengths and weaknesses and agree on what we’re doing in this meeting, in this finite period of time to get things done most efficiently. Then the storming goes down, then the norming occurs, and you start to work better as a team.

So in summary, that’s just a high level snapshot. I couldn’t even explain this properly in an hour. I apologize. But the Tuckman model of team formation does identify stages of development. Storming is the low point, the one people like the least, and we tend to waste a lot of time there. Get bogged down an argument. A way out of that usually is some form of survey tool, learning from each other, appreciating each other, respecting each other, discovering things in some way that we can build upon each other’s strengths, and not just put down each other based upon their weaknesses. And look, different personalities, behavioral activities, learning styles, all have strengths and weaknesses associated with them. The problem is when you know one way, or think your one way is best, and try and force that in everyone, then you just invite resistance from the other quadrants and things like that, then the storming phase just extends, extends.

Back to the Virtues

Good coaches have to think about this and manage all situations and personalities and types of behavior to get the most effective results in the shortest period of time. So I end this again with the seven virtues of martial arts. We want to practice integrity, we want to practice respect for others. It’s not just respect, you got to have more than that. You have to have courage to do the right thing. Let’s do the honorable thing for the long run. Let’s practice compassion, and thinking for everybody involved in the equation, let’s be honest with the facts and data, and let’s do our duty to the best we can, and have a great problem-solving effort. So I hope this helps you think more broadly about problem-solving and coaching, and in the next video we’ll go on to another topic, and things that I think will help you further explore the topic of coaching and problem-solving. Have a great day.