From the beginner stages to the expert roles, there is always room for improvement in the ways that we develop, learn, and coach. Art is back with the Dreyfus Model and the stages of learning acquisition, providing more ways to lead with purpose. Find a lightly edited transcript below.

Part seven of eight. Watch the others:

Part one, Coaching Problem-Solving

Part two, Lessons from NBA Coaches

Part three, Lessons from Martial Arts

Part four, Military Science and Leadership

Part five, Tuckman’s Model of Team Formation

Part six, Team-Building Tools and Practices

Part eight, Toyota Coaching Practices

Hi everyone. This is Art Smalley, president of Art of Lean, Incorporated. Today, in conjunction with the Lean Enterprise Institute, I have another short video for you. We are continuing on our theme of coaching and problem-solving, along with how to shorten that lead time to learn, shorten the lead time to solve a problem, and how to shorten that lead time to develop experts.

Today, we’re going to use another external framework. Last time I talked a little about the Tuckman model and the storming phases and things that go on within it. I also shared some Toyota guides with you. But, I also want to use another external framework called Stages of Learning Acquisition.

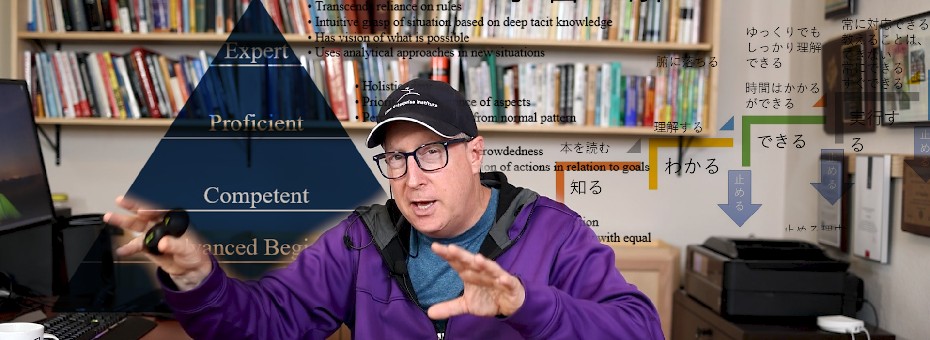

Stages of Learning Acquisition: Dreyfus Model

It’s called the Dreyfus model, and it’s very similar to something we also had in Toyota, at least during my career there. I think it will help you think about the topic of coaching and problem-solving in general.

For background, the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition activity goes back quite a bit. It’s a model of how learners acquire skills through formal instruction and practicing and comes from a couple of brothers who were PhD-level researchers and instructors at the University of California, Berkeley.

Back in 1980, they published an 18-page report on some research they had done with the United States Air Force about how to learn skills, how to develop talent more quickly and things like that. The model proposes that a student passes through five distinct stages in their learning journey.

Depending upon what time you look at it, there are different terms involved with this. There’s the early paper out there you can find on the internet, the PDF file, which has the initial five words they used. Later on, they did author a book called Mind Over Machine, and talked about it more clearly in there in some of the early chapters. I’ll use the verbiage from the later book they wrote, since it represents their later work.

In the Dreyfus model, you go through the stages of being a novice beginner. You go on to an advanced beginner, second stage, then a third stage of having competence, and being able to do things to some extent. Then there’s a fourth stage of being proficient. You’re doing it, and you get quite good at it. The fifth stage is where you become the expert, the instructor, and things like that.

Benefits of the Model

The reason why I like this model, number one, is that it makes sense to me and fits with my own learning journey in sports, martial arts, Lean, and everything. It also mirrors what I was taught in Toyota. Now when I was working for Toyota in Japan, there was a theory of, again, five stages for learning that they used in Japanese. I don’t know the origins of the Japanese framework. To be honest with you, it actually might come from the Dreyfus research. There could be a direct connection there. That’s unknown to me. But the Japanese used five words in Japanese about learning.

The first was shiru. Just passive knowledge. And you think about it all the time, people around the world say, “I know, I know. I know.” Okay, that’s great. But it doesn’t mean you understand or have any ability just because you know something in your head.

A level up from that was the Japanese verb wakaru; to actually comprehend and understand. I just don’t know it, I understand it. A level up from that was the verb for ability, dekiru, meaning I can actually do something. I know it, I understand it, and I can do it at least to some level of ability. Not mastery, of course, but some basic level.

A level up from that was to be able to do it continuously. Different words were used in Toyota versus the graphic I actually have on the page here that I found in Japanese, but it means you have ability and you can continuously do it over time and add some skill as you do it.

Beyond that was the fifth level of mastery. Being the sensei, being able to teach it to others. So kind of a staircase. And of course it’s not linear there’s ups and downs in the real world as you go through it. But it ties in very nicely with problem solving, coaching, I think, and my experiences with Toyota.

Context for the Dreyfus Model

Now, going back to the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition, I’m going to specifically talk about it in the context of teaching problem-solving and coaching people to become better problem-solvers. At the beginning phase of the Dreyfus model, you have the novice. That’s where most of the population is in many institutions.

It’s our job to try and take those people in that category and move them over towards the expert stage, or higher levels of ability as fast as we can. Also, I don’t want to have this distribution that they’re depicting at the bottom. I’d much rather have a narrow or tighter distribution, of course, more centered in the middle or to the right.

But that’s one of the things you have to think about as a coach. How are we going to accomplish that? According to the Dreyfus model, in the skill acquisition stage at the beginning, things like rules are useful because they don’t know what to do. You can’t ask them open-ended questions. What do they think the problem is? What to do? They need some initial skill and instruction. This is right in line with situational leadership, directive situational leadership, or Toyota-style teaching methods for job instruction, and standardized work. You have to give them something to do in the beginning. But that’s best for beginners.

A level up from that are advanced beginners. People who understand the rules, but can also start to think more critically about the situation. So it’s just not passively following rules. They’re engaging their brain and starting to understand that all problems are not equal.

Some things are more important than others in the problem background, the problem definition, or in the root cause section. Those multiple causes, one is bigger than the others. That sort of thinking begins to come in and take effect and you have to coach accordingly.

A level up from that is competence. Here’s the stage where they really start to break away from the passive rules. They think on their own. They realize all problems aren’t equal. They have to be challenged in multiple directions.

You might teach them that, “Okay, safety problem might follow this pattern. Now, try it on a quality pattern and see what’s different. Now, try it on a productivity pattern and see what’s different. Now do it on a profit-loss cost problem and see what’s different,” etc. They begin to develop competency by taking on different tasks and different types of problems, different environments. And of course, different roles within the team in a team scenario.

A level up from that are the proficiency and the expert, the fourth and fifth stages. I’ll talk about them together, because here they’re truly past the rules. They know the rules, but they also know when to follow them, when to not follow them, and how to break them accordingly and invent something better.

That’s why if you actually go in the Toyota books that deal with problem solving that are translated from Japan and show things from the last decade what’s really going on. They’re not doing the eight-step method solely. They’re not just relying upon seven QC tools, five-whys, fishbone. Those are things more in the beginner, more in the novice category.

The important thing as a coach is that you can’t have this one-size-fits-all answer

You get to the expert stage, and this gentleman, Yoshimoto Tatzahico, and he invented something called GD Cubed, and lays out how to do a better FMEA, focusing on very certain critical points and things like that. But that’s more of an expert understanding of problem solving, pre-occurrence prevention. If you look at some of the stuff by Kakuro Amasaka, again, none of his follow the template or textbook pattern that you might think they would, and yet he solves, or was a participant in solving, some of the harder problems that Toyota’s faced in the last couple decades.

He developed people, okay? He broke it up into six categories of expertise in how he coached the specialists in Toyota, who tackled problem solving accordingly.

The Point of it all

My point in sharing this is that most models agree universally, inside and outside of Toyota, there are stages to learning and ability. The important thing as a coach is that you can’t have this one-size-fits-all answer. It works for a class of beginners, but doesn’t work so well when you’ve got intermediate and advanced people in a class.

If we want to succeed at this coaching thing, I think the next level we need to think about in coaching is five levels of coaching, five types of coaching. And ways to go after things in a way that makes sense for the person you’re trying to work with and deal and instruct, and build more ability throughout the levels of the organization.

So, I hope that helps you think about this. In summary, Dreyfus model of skill acquisition, touched upon that. I compared it to my experiences at Toyota and the concepts of stages of mastery that they had. I’d like you to be very aware of the learner’s ability when you’re coaching and how you coach them accordingly to get the best result for yourself, for the team, the organization, and just in the spirit of respect for people as well. Have a great day.