Art shares some specifics about Toyota coaching practices. Find a lightly edited script below.

Part eight of eight. Watch the others:

Part one, Coaching Problem-Solving

Part two, Lessons from NBA Coaches

Part three, Lessons from Martial Arts

Part four, Military Science and Leadership

Part five, Tuckman’s Model of Team Formation

Part six, Team-Building Tools and Practices

Part seven, Dreyfus Model and the Stages of Learning

Hi, everyone. This is Art Smalley, president of Art of Lean Incorporated. Today, in conjunction with the Lean Enterprise Institute, I have another video for you on the topic of coaching and problem-solving. We’re getting near the end of our series, but I want to talk about a couple more things related to coaching and problem-solving and shortening the lead time to learn.

I talked last time about an external framework called the Dreyfus Model, and I’ve shared some internal Toyota things. I had a question sent to me, “Art, can you show more about Toyota’s actual coaching practices, not the theory?” I said, “I’ll do my best.” So in this, we’re going to talk about that topic, so stick around. I think you’ll enjoy it.

Coaching Practices at Toyota

In response to the question what are actual coaching practices like in Toyota?, to be honest, it’s quite varied. I experienced it in Japan. Those of you who have worked for Toyota around the world might have similar or different experiences, but you learn on the job in Toyota. You learn by standard training, you learn from your peers, you often learn from people assigned to you. They’re, in Japanese, called a Sempai or someone superior to you. Like if I’m a junior engineer, there’s a senior engineer who often oversees my work. You learn from managers and specialists in various realms. Eventually, you learn from advanced courses if you stay with the company long enough and advance through positions. You learn from various special problems and assignments you’re given over time. So it’s not a one-size-fits-all.

Now, what I do have, interestingly, is my basic problem-solving handbook that I was given 30 years ago, over 30 years ago, when I went to work for Toyota in Japan. It has a grand total of 44 pages, only five steps in this one, believe it or not, seven QC tools, and some examples and a glossary. That’s all I got when I started working. It’s a form of basic problem-solving training, and I didn’t get any coaching specifically on this. You’re expected to then go and apply and work on a problem, and then you’d get some coaching after that.

Later on, I did get a bigger one, fewer pages, but this was intermediate problem-solving in Toyota. This one has 13 pages. I guess the higher you go, the less they’re going to give you in terms of knowledge. This one did have the actual eight steps though it is outdated. The eight steps that you’re doing today are not exactly the same, but this would be considered the routes of the eight-step method that Toyota has in its Toyota business practices, practical problem-solving routines of today.

To be honest with you, there are also advanced topics. I got to experience some of this in Toyota — very advanced techniques in problem-solving. You don’t hear about these, sadly, on the outside, but there are experts in Toyota, using very advanced techniques. There’s specialist training and coaching going on for a very small segment of the population, very statistical in nature, very quantitative. But, again, it is for the select few in quality control, product development, reliability engineering, and things like that.

The man who knows the most about it, a gentleman named Kakuro Amasaka, is retired. But he did publish a book that has some material pertaining to that if you’re interested. It’s not a great book, not well translated, sadly. But it gives a little bit of a picture of that. An example is a steering pump hose and an improvement project problem they were solving. He points out the different ways you can tackle this problem through reliability engineering and Weibull analysis and various tools: regression analysis, principal component analysis, multivariate analysis, and things like that. And, of course, design of experiments.

It Depends on Your Level and Position!

You’ve got to realize that actual coaching practices and problem execution really depend upon your level or position in Toyota and what you’re doing. It’s not one-size-fits-all. But be that as it may, let’s circle back to, I think, what the questioner was looking for.

What are basic problem-solving and coaching practices really like in Toyota? Here’s a picture of a lady doing a problem-solving report-out to a team leader and a manager, which is what happens to pretty much everybody. You complete some basic training. You get assigned a problem, maybe team-based, individual-based; it depends. You work on that problem, and there are periodic report-outs, and you receive coaching during those report-outs. You might do two steps of problem-solving, have a report-out, get to step four, have a report-out, step six, have a report-out, step eight, have a final report-out, things like that. You get coaching and advice through those steps and, of course, struggle on your own.

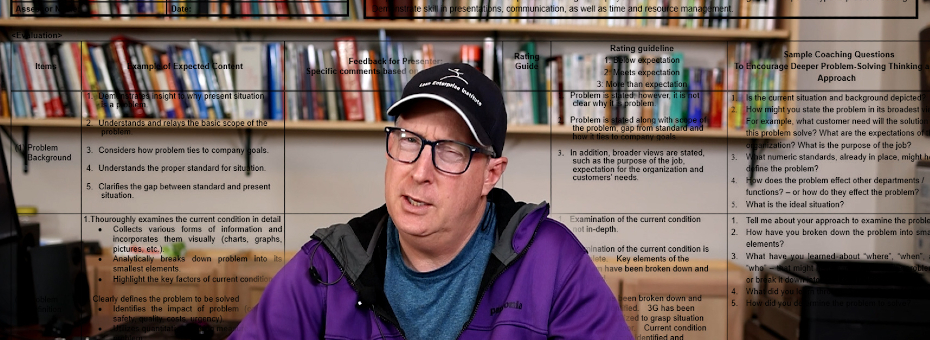

Interestingly, there is an actual Toyota form used for coaching. I have an old version of it that I translated from Japanese, and to my knowledge, Toyota has not released this to the outside world, so I can’t freely distribute it. But I think it is floating around, to be honest with you. I’ve seen multiple versions of it, even in English. It specifically shows what the Toyota coach is expected to do in terms of feedback and working on problem-solving with a given team or individual. It has steps. It has content that you’re supposed to look for. It has an area for feedback to be filled in. You as the coach, must provide a [numerical] rating. It does have questions you can ask, very targeted questions to ask for feedback.

In this way, it is very much like situational leadership. Toyota is not a one-size-fits-all model, and the coaching forms, especially at the intermediate and advanced level, are quite flexible if you look at them and think about it. There are directive, coaching, supporting, and what I would call delegative, or good S4-style, coaching components, which are in the spirit of situational leadership.

Specifying the Steps

Now, to get more practical, the directive aspect of it is something like this. In the Toyota coaching form for problem-solving, you have to specify what the steps are and the expected outcome. You just don’t let people struggle. Of course, they get their basic training, but as a coach, you’re also explaining the steps, the expected outcome, what it looks like, and providing that quality instruction that people need.

Secondly, a level up from there, you’re also evaluating the content. So, you’re coaching and evaluating the content. You’re just not simply asking questions. You’re seeing what the student did versus the standard, and you’re giving them a rating of one, two, and three. One is “does not meet the expectation.” Two is “meets expectation.” Three is “exceeds expectation.” But as a coach, you have to say why. So in problem-solving steps one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, all eight steps, you have to rank it one, two, or three. You have to say why it does not meet expectation, why it meets expectation and yet still could be better, or three, obviously, if it exceeds expectation, explain how it exceeded expectation what was really good about it. But that’s good coaching.

That’s one of the difficult things about being a coach. You don’t give them the answer, but you also give them enough instruction so that they know the next steps to go forward.

Thirdly, there’s a supportive aspect of it. People who are kind of getting the steps and doing the content mostly right, but still need a few areas would get what we’d call S3 or supportive leadership, supportive coaching. You’re going to ask them targeted questions. The mistake I see in coaching is we’re just asking open-ended questions and expect the learner to figure it out. The Toyota coaching feedback questions are all targeted and quite directed. So for each of the eight steps, there’s a half dozen, five or six, questions. There’s anywhere from 40 to 50 targeted questions in there, in the coaching guide you ask the learner to help them think about the problem they’re faced with and what they might get a better idea or understanding from that targeted question.

That’s one of the difficult things about being a coach. You don’t give them the answer, but you also give them enough instruction so that they know the next steps to go forward.

Not anybody’s allowed to be a coach in Toyota. I think that’s one of the problems or misconceptions we have, that just because you can do problem-solving, you’re a good coach at it. That’s not always true in Toyota or the real world. It’s somewhat restricted to the better problem-solvers and the coaches with that capability, especially when you get to the statistical quality control, SQC, realm. It’s very advanced in Toyota, and a very, very small percentage of the population is as qualified to do that.

Toyota Coaching Overview

In a video, without going into an actual step-by-step problem, that’s the best I can do, trying to explain actual coaching practices in Toyota, what they look like, by level and by type, and by the situation. There are very advanced courses. I’m sad we don’t get to talk about them, but they’re very restricted in terms of access, and who gets to take those courses — and who gets to coach those is even more restrictive. I tapped out in the middle — at about the intermediate SQC level and multivariate regression analysis.

There are, of course, beginner courses that everybody sees and knows. That’s where you start. There are beginning guides, as I talked about, but it’s not one-size-fits-all. The best coaches know how to be directive, coaching, and supportive, and they know how to ask targeted questions that help people advance down the path of problem-solving. To me, that’s good coaching and the direction I hope we can go in the future with lean and problem-solving and other topics of a similar nature. So I hope that helps. See you in the next video.

Intro to Problem-Solving

Learn a proven, systematic approach to resolving business and work process problems.