Dear Gemba Coach,

As a Lean “facilitator” in my organization, how important is it to gain a deep understanding of the “area” that is being analyzed. Do you find you spend a lot of time just becoming familiar with the area so that you can do experiments, etc.…?

It’s critical! Bear in mind that the very engineers who “invented” lean (more like, cobbled it together) were the same guys who had learned to make automobiles from scratch and build factories in paddy fields!

At its core, lean thinking has a very scientific idea: by studying the part of what we do that doesn’t work as it should, or that is unwanted waste, we discover a deeper understanding of our jobs. As legend has it, penicillin was discovered when Alexander Fleming returned from vacation to find a new fungus on a culture he’d left in his lab. An American engineer working at Raytheon noticed that the chocolate bar in his pocket melted as he walked past a magnetron, a vacuum tube used to generate microwaves, and then experimented until voilà, the microwave oven, and so on.

Many discoveries, from the big bang theory (discovering a background noise that made no sense) to Velcro (an engineer shaking burrs off his pants and his dog’s fur), seem accidental. But truth is these “accidental” ideas occur to people who have devoted their lives to studying the topic.

Another way to think about this is to keep in mind the following equations:

DATA + CONTEXT = INFORMATION

INFORMATION + UNDERSTANDING = KNOWLEDGE

KNOWLEDGE + RESPECT = WISDOM

In other words, real knowledge is profoundly contextual, and general context-free principles are generally not that useful without a deep understanding of the situation. Worse, wild applications of scientific ideas like Darwinism, Behaviorism, Genetics, Neurosciences and so on, can lead to horrific applications once taken out of context.

On the gemba, lean is a mental scaffolding, a mathematical operator, if you will, that applies to the area, the people, and the technical process at hand in order to discover deeper truths about it. Without this fundamental respect of both people’s experience and the technical issues of the process, one can make really bad mistakes.

The 5S Badger

For instance, I recently visited an office where the manager insisted on “office 5S”, which essentially meant badgering people into clearing their desks in the evening and moving towards a no-paper policy. This policy was imposed without any understanding of the team’s “standardized work” or, indeed, “operations standards” – the work itself. As a result, teams didn’t set upon taking more ownership of their filing systems, nor discovering more detail of what the information truly meant and, in the end the “clean desk” policy created more frustration and disengagement as people had to comply with yet one more absurd request from management.

On the other hand, at another company, a high-tech manufacturer, the early attempts to sort out the supply chain flow led to a deeper and deeper understanding of the information flow, and a realization the company had no consistent indexation of blueprints, parts, and so on.

By continuing to delve into this arduous (and contentious) issue, a cross-functional team of managers tackled the Bill Of Materials rather than delegate that problem to a software vendor. By blending the team’s technical knowledge of the machines and progressive understanding of how the information hiccups across the development process, the team set upon redesigning the entire information flow within the development, production and procurement processes.

Information kaizen at Proditec (the heads of supply chain, production, optics, mechanics, HR and CEO) PRODITEC is one of the case companies in our new book The Lean Strategy by Dan Jones, Jacques Chaize, and Orry Fiume.

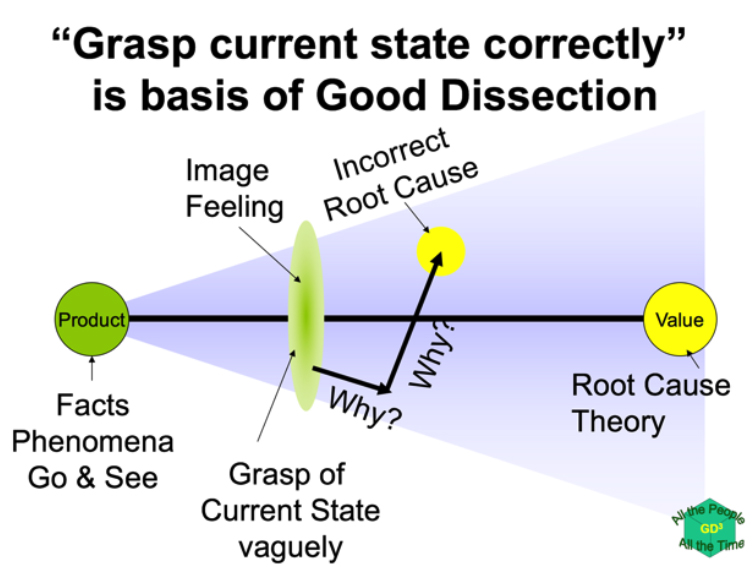

A deep understanding of the area is absolutely essential to lean – to a large extent, it is the whole point of lean: better observation and better discussion to deepen the understanding of what we do where and when. Without it, asking “why?” five times is pretty futile, as explains Toyota veteran Tatsuhiko Yoshimura:

I’ve had to learn his lesson myself the hard way. I was fascinated by Toyota’s lean approach at a supplier as they “made people before they made products,” and so committed to learn what Toyota meant by “making people.” It took me four or five years to reconcile myself to the idea that this simple sentence could only make sense in the context of “making products” – which is when I realized I had to grasp the engineering of the products I was looking at, and, in the end, drew out a radically different understanding of lean itself.

I know, this sounds very challenging. I’ve been where you’re standing, and it’s really tempting to think that “process skills” can add value – and to some small extent they can. But what really matters is intent: the intent to better see how people understand the products or services they put together and how to use the visible muda to deepen their technical understanding, so that they find innovative solutions to existing problems.

Don’t let yourself look at the finger rather than look at the moon the finger points to. Taiichi Ohno’s seven waste of overproduction, waiting, conveyance, overprocessing, inventory, motion, and correction are specific unnecessary operations that are wasteful in a work cycle – but there for a reason. This list is there to draw our attention to the technical causes of these wastes. Only a deeper technical understanding of the physical and engineering processes can lead us to eliminate these wastes as well as, often, getting lucky and discovering entire new ways of providing value.