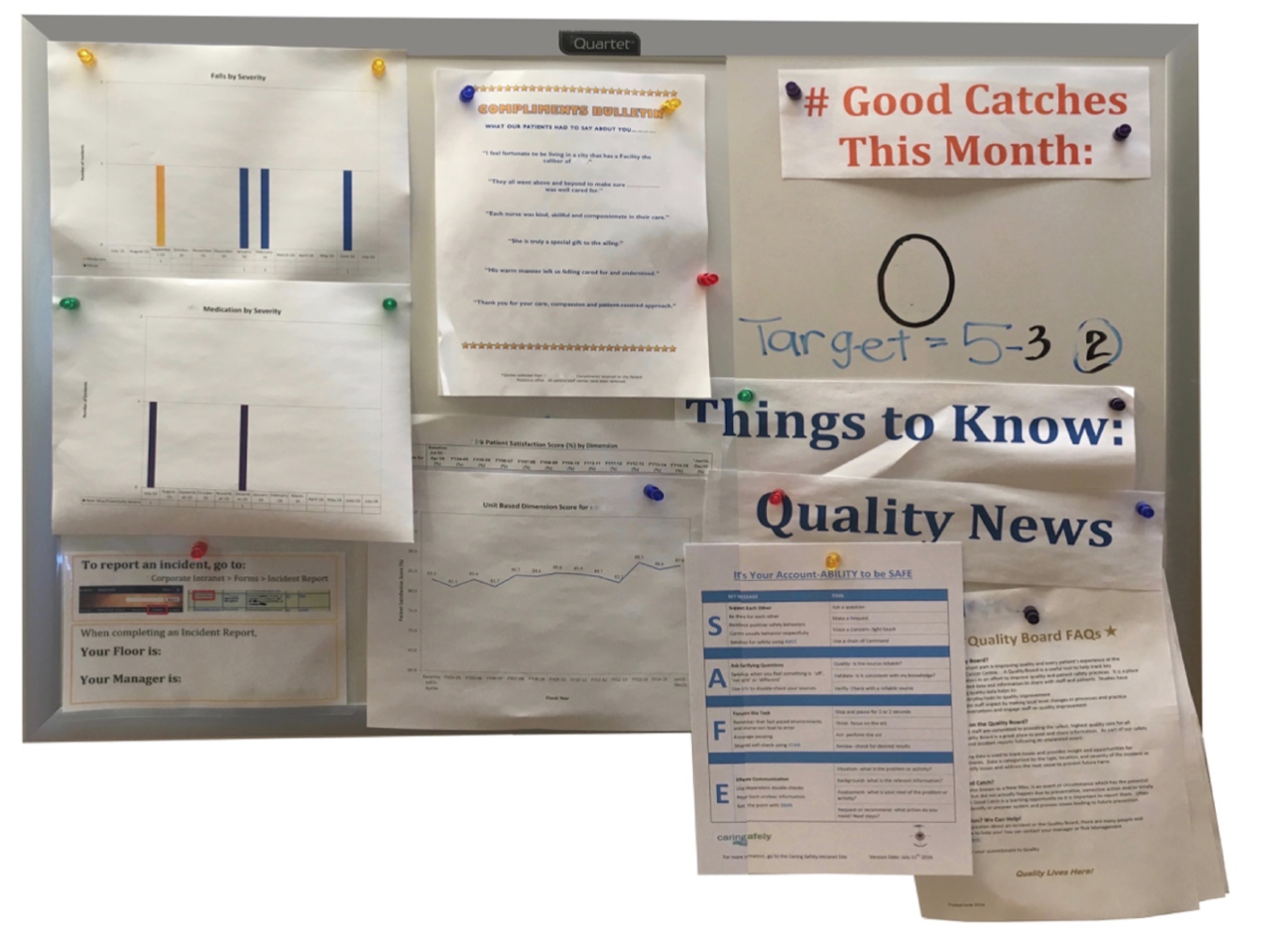

Recently, I had the bad luck to become an overnight guest in my local hospital. While recuperating, I was encouraged to get up and walk around. So, I set out on regular walks around the unit. On one of these walks I stumbled on the team’s dashboard.

I studied it for a while. I wondered how the staff on the floor used the information. Most of the data was charted monthly, a bit late to prevent the next incident. I think there were 2 good catches this month. What were they? If I worked here how to I tap into this intelligence? I can’t complain about the “Things to Know.” Watching the staff however I wondered if there were more relevant or practical things to know such as how to find a medicine in short supply or why a certain piece of equipment isn’t working. This got me thinking about my struggles to set up an effective dashboard system. I started learning the concepts when I was a production supervisor. I was one of the last departments in my plant to implement a dashboard. If I were honest about why it took me so long, I fought the idea of making the things I knew weren’t going well visible for all to see. At the time we lived in a world of computer reports. We never hung information on the wall. I did have a good sensei though who taught me how to walk the floor and understand the status of things. I stopped using the reports because my walk throughs gave me better information. I knew when things weren’t going well. And I didn’t always know how to correct things right away. So when member from the Lean Office approached me about making production numbers visible I just got nervous about looking like a failure.

In fact, I procrastinated with my first dashboard so long, my team put it up while I was away on vacation. At first, when I returned, I was furious. I felt as though my team had gone behind my back and put all our problems up on display. Any performance indicator off target, made me feel incompetent. It was hard at first but over time I realized a solid debrief over the things that mattered, every shift, was a phenomenal way of engaging the team around what is important. They all rose to the occasion, as I never doubted them to do, but it truly was heartwarming to see. Upon reflection over time, I came to believe that this happened because they created the dashboard, not me. It was what was important to them. Sure, not all the elements were aligned well to the organization goals, which created spirited debate. But after taking many runs at this hard work, we were able to make real progress.

Coming from a manufacturing perspective, I was used to my dashboards being out in the open for anyone to see, like this one. Any customer could see it; it’s just that they rarely do. It takes guts to put problems out in the open for anyone to see in a hospital unit, and I am impressed with that. However, my admiration for people taking the risk of visualizing the work was balanced by a critical eye towards what I saw as ambiguous goals and out of date information. I thought about the most well-known of dashboards, the one in my car. What if it was plastered with the phrase “drive safely?” Or the gas gauge had last week’s or last month’s fuel levels? Or the numbers removed from the speedometer? How could I make regular adjustments to my driving without having to take my eye off the road? I couldn’t help but ask how this dashboard could help the team here to make regular adjustments to their work without taking their eye off me, the patient?

Over the last twenty years I learned through trial and error the most effective approach to dashboards. People deserve to know what is expected of them and need to have a voice in how the work is done. With that in mind below are my 3 biggest learnings about what it takes to create a system that people depend on.

First, it is difficult to put good numbers on a dashboard. You will wrestle with: what are the best measures of success? What should our target be? How can we easily get actual performance frequently? Don’t skip this step. The objectivity of the number play a critical role in creating the right conversation. Don’t over complicate the exercise of picking metrics for your dashboard either. A good leader (and her team) already watch their team and have developed parameter which tell them whether things are going well or not so well. They might not be quick to articulate what they watch, or you may see different thresholds of tolerance. Setting up a dashboard is about tapping into something already being done.

A good dashboard brings the collective knowledge together on unstable variables and centers it against a target. Of course, it isn’t about the number. It’s that the number provides the threshold in which a conversation about possible intervention must take place. Going into surgery my blood pressure was taken. It was high. Not because I have chronic high blood pressure but because I was thinking about all the things that could go wrong during surgery. When the nurse took my blood pressure, she didn’t focus on a number without context. Rather she saw I was off-target and hit the pause button. At that point the nurse and the anesthesiologist determined the best intervention for me. In the hospital unit where I was staying, I might be interested in how much time I, as a nurse, had with my patient. Too little? Too much, keeping me from other patients? Maybe also some qualitative measures such as how many patients are a fall risk or are having difficulty with pain?

Second, good dashboards don’t penalize anyone for missing target–showing up as red. In fact, any good and rigorous dashboard will always have reds. That’s an inevitable result when dashboards are always be up to date as they should be. Imagine if the nurse had used my blood pressure from my pre-operative visit days before my surgery. In that case she would be making decisions using old information. Or worse, what if she thought she would be blamed for my high blood pressure. Of course, it wasn’t her fault my pressure was a little high; I was just very nervous about surgery. If she was made to feel at fault, especially with few levers to correct the situation, she may not take my pressure at all, or hide the numbers. My sensei many years ago told me, “no problem IS a problem.” It took me a long time to internalize this idea. I had to create an atmosphere of trust where teams who stretched for what was just beyond their capability (i.e. were often red) became the rock stars with greater rates of improvement. Those who played it safe (i.e. were often green) needed greater attention. Trust had to be developed so the team could reach further and not feel failure would give them a black eye.

Regardless of how aggressive a team sets goals, without current off-target conditions your dashboard will be ineffective. Keep in mind the things measured on a dashboard may typically be items that need be watched closely, because they have a propensity to be unstable. Reds are to be expected and make a good dashboard useful. As I was given more responsibility and a new title, my dashboards continued to evolve. What I found to be always true, for myself and for others, is the best target is something just out of reach. It forces us to be tough on ourselves but not punitive toward each other.

And third, every meaningful indicator frames the problem in a way that helps brainstorm and choose tangible actions about what could be done to make the work better. These ideas should come from the people who do the work, not from the boss. How many of us like it when our boss tells us how to do our job? Our dashboards had a simple rule: for every red, at least one idea had to be generated. It should cost nothing and could be completed by the staff who do the work. That was a tough rule, but it got our creative juices flowing. Not only did we know what was expected for success, but we started to control the things that led to our own success.

I suggest that everyone build a system of dashboards up and down the organization. Connect them so ideas flow upward and support flows to the idea. It’s a bit tricky setting up dashboards that summarize the performance and capture the critical ideas of many departments below, but it can be done through trial and error.

If you’re a boss, demand these ideas. Don’t intervene in the work. Rather, capture them, understand them, support the ideas and the people and get out of their way.