My work with Lean thinking took a personal turn a little over a decade ago when my own health threatened to sideline my career. At the time, the true nature of the problem wasn’t clear to my doctors because my symptoms mimicked other conditions, making it difficult to diagnose in one or two visits. Consequently, they prescribed “countermeasures” that they thought would improve my current state. In reality, these efforts were temporary countermeasure, based on an assumption, and led to worsening symptoms.

In the medical world, there are different types of conditions which are sometimes described as a “zebra”. The analogy is that if you were blindfolded and heard a stampede of hoofed animals coming your way, you would assume, “ah, it’s a herd of horses.” If there were a few zebras among them, you wouldn’t be able to determine that because they have very similar hoof sounds when they run. But if we go to see them up close, we recognize those zebras placed sparsely herd. In the medical field there are often zebras (medical anomalies) among a group of horses that defy what is generally assumed to be the case. This often happens in our work life as well, when we fail to ask the right questions because assumptions have been made based on general experiences, ones where we tribal knowledge pulled us through the situation. My trainer would say this is “lucky”, but lucky isn’t a sustainable process in every case.

My doctors were being guided by their assumptions and what they had been trained to look for in 90% of patients they see. After a sequence of doctors were unable to deliver a diagnosis, I turned to what I knew best: PDCA, and Toyota’s 8-step problem solving process. My quest turned into a journey of more than seven years, with small celebrations and discoveries along the way. I was leading and learning with some of my doctors who happened to look a little deeper than the first “potential cause”. I was given countermeasures to deal with the symptoms, but these were only temporary, and I knew we had to get beyond the symptom and on to the root cause(s). Fortunately, thanks to my training, finding root causes was something I understood deeply. As my trainers taught me “there is always something looming behind the first one.” In my case he was right. Unfortunately there were several.

And so I literally became my own gemba, carefully tracking the ups and downs of my daily symptoms and recording the data in a 3-ring 4-inch binder. I had a “should be” state (healthy and able) and I had a current state; I organized this information with an A3. Using the data I collected on myself (sometimes hourly), I slowly began to break down the problem into manageable pieces to rule out or to narrow down some of my contributing factors, just as I would would teach anyone looking at a large complex problem.

This was my life for several years. I was managing up until the last part of my journey, when I had declined to the point I was unable to effectively do my work. I knew there was something deeper causing this, but lacked the specialized medical knowledge I needed to get the answers.

What I had managed to do was create an elaborate breakdown of the problem, eliminating as many possibilities as I could, focusing on the weighted data points affecting me the most, and trying to see specialists in those fields in the meantime.

This led me to a cardiologist who wasn’t far from retiring and was what I would consider very knowledgeable and old-school. He was also very methodical and seemed to have a process which I dubbed as “gained wisdom”. After noticing a certain symptom (point of occurrence) during my exam, he checked a couple of my vitals first when I was lying down, then sitting up, and then standing up, all about five minutes apart. This was a unique protocol because he noticed an abnormality that others hadn’t taken the time to do. Then he was silent for a few seconds and asked me if I would be willing to do it all again for confirmation. In our work this would be retesting or piloting a theory again to see if the same results occurred.

I felt very comfortable with this doctor. He was thinking, testing, and confirming his thoughts, just as I had been taught to do. He was able to confirm the condition and prescribed a different countermeasure that dialed in on the problem much better, but my quest wasn’t over. It turned out that this condition is highly complex and can have a variety of root causes which were beyond this doctor’s expertise. So think of an onion, we just peeled back the 1st and maybe 2nd layer, but were much further along that I had ever been to this point. So a base hit for me.

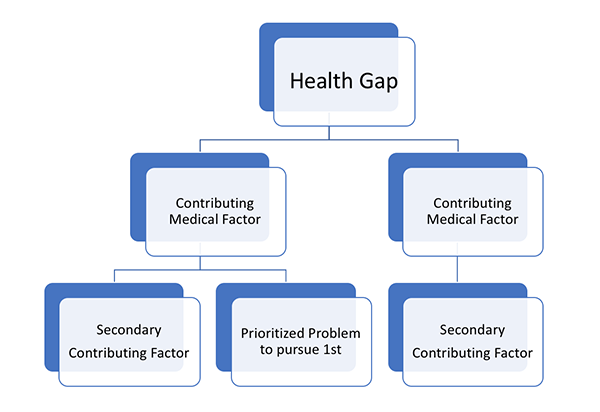

I was disappointed we couldn’t “fix it” since for this particular facet there was nothing to do but manage it in various ways. But in the same breath I was excited that we seemed to be moving closer to that root cause(s), and was more determined than ever. I continued to study and gather as much information about this condition, and eventually went to see another specialist almost 200 miles from me at that time. This doctor was familiar with my newly diagnosed condition and did further tests to confirm some questioning around certain areas of concern he had based on the data I had collected. All the tests came back positive, confirming just how complex the condition was, perhaps having 25-30 layers to the onion now. It was as if my breakdown of the problem had many child level A3’s from the main gap. But I kept asking “why” and followed the instruction from my trainers to “never give up”. My livelihood was at stake.

For the information I gathered from the specialist 200 miles west of me, my path finally led me to an appointment with a specialized cardiologist at University of Toledo, who had established a worldwide reputation for his work with my condition. I was thrilled that he would see me, but was immediately deflated like a balloon popped by a pin when I was told it would be a 9-12-month wait. It’s discouraging when you feel you are on the verge of getting back to a somewhat normal life, but to be halted because there are so many others ahead of you in the line. I had to manage the fact this was a minor setback but I would still continue to work towards the ideal state with the information I had. My countermeasures were allowing me to maintain and my discipline and accountability to living life different was crucial for my longer-term sustainability being a bit compromised. Sometimes in our work-life longer term fixes take time and temporary countermeasures can seem permanent at times in complex issues.

My time finally arrived and we flew up to Toledo to see this doctor. I brought my familiar 3-ring 4-inch binder with all my data I had collected for several years now. He did a thorough clinical exam based on his field expertise and ask me a slew of questions. Then, he sat down as if this was a routine and began to explain to me what was wrong and why. What he presented to me was quite different from what past doctors had shared with me, and presented a tangible explanation where all the “whys” ended. It turned out that I have a rare genetic condition that affects 1 in 5000 people, and there is no cure and could progress – it is unknown at this time.

At that moment it was if a 100-lb weight was lifted off my shoulders. After all the studying, documenting, measuring and asking questions I had my answer (root cause/condition). As he went on, I cried. They were tears of joy and sadness at the same time. It’s not often the words you always want to hear, but it was the answer that I had worked so hard to find.

This condition has varying degrees of severity, and a number of possible symptoms. I consider myself one of the lucky ones that can manage the “invisible condition” from the outside and still have a somewhat normal life. I have had to change my lifestyle in numerous ways in order to maintain control over the symptoms, but I now lead a relatively normal life, and most people would never know unless I told them. I have learned to mask what is on the inside. I fly to make annual and biannual visits to three specialized doctors, including a geneticist without whom I couldn’t continue to do what I do. These specialists help guide my local doctors to get what I need here in Florida, and I attend annual conferences to lead and learn with others like me.

Today I keep current with the research (and try to be the research) on this condition for myself and others. I am part of a group working to make doctors more aware of zebras, and the importance of using problem solving when confronting complex medical problems. I now share my story with others on their medical journeys as a testimony that problem-solving can change lives for the better. Thousands of people suffer from undiagnosed or more complex medical conditions that mimic other conditions. When it’s all said and done, I truly believe I wasn’t just selected to work at Toyota building people and cars. I was hired there for greater purposes that I wasn’t aware of at the time: – to save my own life and guide others to make a difference in their lives (work and personal).

The passion I have for this thinking is deep and most people who have been in our courses can see that. I am thankful they taught me how to think differently and I hope that through the wonderful training I received at Toyota, I am helping to make a difference. Every day is a learning journey to manage and maintain just as many people do daily in their work life, they are often not that much different. Never give up and never stop learning!

(Read more from Tracey and Ernie Richardson in their new Shingo Award-winning book The Toyota Engagment Equation from McGraw-Hill.)