Best in Healthcare Getting Better with Lean

Mayo Clinic Division of Cardiovascular Diseases improving patient-flow processes.

By George Taninecz

The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN., is one of America’s elite organizations and world famous for the quality of healthcare that it provides. Fortune magazine named Mayo Clinic as one of the “100 Best Companies to Work For®” in America, the third year in a row that the organization was tabbed for this annual compilation of companies that “rate high with employees.” For 16 years in a row, U.S. News & World Report named Mayo Clinic one of “America’s Best Hospitals.” Even though Mayo Clinic is at the pinnacle of patient care, leadership keeps looking for ways to improve — and now they’re looking to lean.

Mayo Clinic comprises more than 2,400 physicians and scientists and 30,200 allied staff working at the original clinic in Rochester and clinics in Jacksonville, FL., and Scottsdale, Ariz. Mayo treats more than 500,000 people each year. Multiple medical disciplines at Mayo set the healthcare standard around the globe, and few specialties have more prestige than Mayo’s Division of Cardiovascular Diseases.

“This organization has a very strong culture, has a very rich history, and always has provided the very best patient care. We’ve done that with the great people that we have. We have probably the best nursing staff, physician staff, and allied health staff that I’ve ever encountered in my over 20 years of medicine. It’s phenomenal,” says Dr. Henry Ting, Practice Chair, Division of Cardiovascular Diseases. “Having said that, I do think we have opportunities to improve our processes to provide better quality, safety, and service, as well as to delight our customers.”

Many organizations are drawn to lean thinking in a time of great need, desperately seeking to operationally improve and reverse their fading fortunes. With the Mayo Clinic’s cardiovascular division that was not the case: “We certainly did not come to this because there was a ‘burning platform’ where we had to change,” says Dr. Ting. “Our change has really been because of enlightened leadership. Dr. David Hayes, [Chair of the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases], had the leadership and foresight to say, ‘We can do better. We’re doing good right now, but we can do better.”

The lack of a burning platform, though, can present challenges, notes Dr. Ting, especially among physicians who see world-class care all around them. He tells them, “I’m not trying to change the moment of care, the touch moment between you and your patient.

What I’m trying to change is the 95% of the time when the patient is not in your office and you’re not seeing them or providing care to them. And that’s the 95% where we have opportunity for improvement.”

“The point when doctors are willing to accept [lean] is when they grasp the concept that you’re eliminating the waste that gets in the way of them doing what they’re there to do

— the care moment,” says Doug Parks, administrator for the cardiovascular division. “And we made it clear in all of our projects related to patient flow that the moment of care, when a physician was with a patient, was off limits. What we’re trying to do is expand that time, give them all the time needed to provide the best care they could.”

Dr. Hayes became aware of lean through initiatives within Mayo’s radiology and pathology departments, where movement of materials and inventory (e.g., film and samples, respectively) is core. The Division of Cardiovascular Diseases was faced with the added complexity of processes tangled with people, information, and material.

Priority projects included:

- Cardiovascular Health Clinic (CVHC),

- ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI),

- Inpatient Admission and Triage,

- Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory,

- Echocardiography Laboratory,

- Complex Ablation Access,

- Warfarin Safety, and

- Outpatient Appointment Redesign.

“The unified focus has been ‘process improvement’ or how we do our work’” says Dr. Ting. Initiatives for CVHC and STEMI have been in place the longest and each, in different ways, has helped to advance Mayo’s mission to “ … provide the best care to every patient every day through integrated clinical practice, education and research.”

Flow Through CVHC

The CVHC is Mayo’s preventive cardiology clinic focused on the needs of people of all ages at risk for heart disease or those already afflicted with heart disease. Services include risk assessment (based on multiple diagnostic modalities) and risk-reduction services (developing action plans for patients that include physical counseling, weight loss, nutrition counseling, smoking cessation, etc.).

CVHC was the rollout target for lean because of problems with no-shows, cancellations, perceived lack of demand, and dissatisfaction among both allied staff and physicians with the efficiency of the entire patient journey, especially scheduling appointments — too many handoffs, loopbacks, and wasted time. For example, appointment coordinators were responsible for managing patients up to the time they physically entered the CVHC, then a clinical assistant took on that role until 30 days after the patient left CVHC, and then the patient reverted back to an appointment coordinator; a patient might be asked three times for the same information by three different people. Additionally, appointment coordinators rarely saw the patient or even the physician, making communication and problem resolution difficult.

Angie Wills, operations manager for the cardiovascular division’s outpatient practice, says that the many opportunities to improve the CVHC practice combined with a new director, Dr. Randal Thomas, who was willing to lead changes, made the center a logical first initiative. Jonathan Curtright, administrator for the cardiovascular division, adds,

“It’s also a snapshot of the division: It’s got a huge outpatient practice, an in-patient practice, a laboratory with exercise testing, and rehabilitation services, so if we can get [lean] to work in that setting it will probably work in other disparate settings within the division.”

Success for CVHC depends largely on providing diverse, high-quality cardiovascular care in a brief period during which physician time is sandwiched by various testing and counseling procedures. “Cycle time, or completing the patient itinerary, is important,” says Dr. Ting. “When you come here for a comprehensive evaluation, we strive to complete it within two to three days.” Many of Mayo’s cardiovascular patients come from around the world. For them to come back for tests in a week or so isn’t practical. Coordinating a patient’s visit requires aligning various disciplines for the patient’s trip to Rochester — capture of personal data, request for outside materials, securing physician time, ensuring lab time, etc. — which often meant multiple tries before an appointment satisfied patient, physician, and other CVHC schedules.

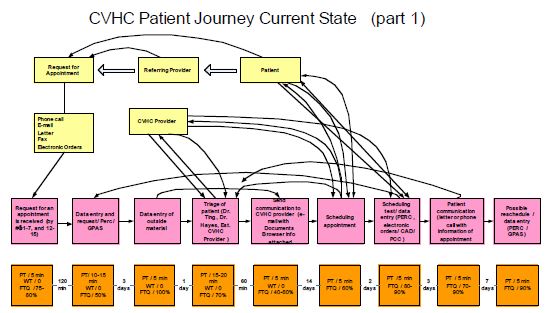

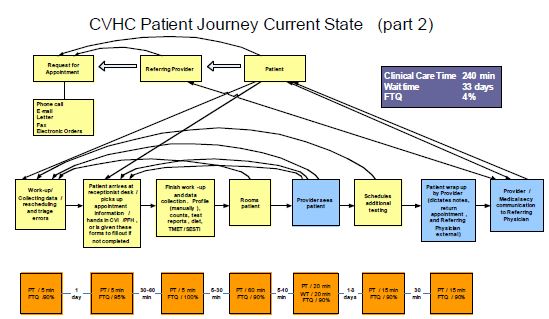

In March 2005, staff studied the patient process in a traditional lean manner, first by attending a three-day workshop where they mapped CVHC current state. They reviewed the entire process as a patient initially contacted and then moved through the CVHC system, from scheduling an appointment to post-treatment followup, and they tracked process time, wait time, and first-time quality. Based on those findings they envisioned a future state and established 30-, 60- and 90-day goals to help them achieve it.

The CVHC lean team implemented:

- Patient risk-assessment intake-triage process using existing registered-nurse (RN) staff. (This process previously required input from RNs and CVHC providers.)

- Standardized protocol for diagnostic testing, evaluation, and treatment based on clear guidelines of cardiovascular risk levels (low, moderate, high, early arthrosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome).

- Standardized care models for each risk level (defined roles and procedures for doctors, RNs, dieticians, exercise technicians, etc.).

- Standardized procedures for preparing previsit information (eliminate duplication and rework).

- Standardized process for patient education, clinical consultation, and how patient hand-offs are communicated.

- Pull scheduling for tests on demand (open slots were incorporated so that CVHC patients could get same day echocardiograms and stress tests).

- Shared job functions for appointment coordinators and clinical assistants, which reduced rework, improved staff communication, and enhanced job satisfaction.

Following the initial lean work, cancellations and no-shows dropped from 30% to 10%. The number of high-yield patients rose from 150 per month to 200 per month. An appointment could be given 90% of the time on first contact with CVHC.

“You want to anchor that first phone call,” says Dr. Ting. “We talked about it at our lean workshop: when you make a reservation at a restaurant, you book the time, you don’t

book your appetizer, entrée, drinks, and dessert. So we wanted to book the time, because this was the most difficult issue — the appointment slot with the doctor. Everything else we could pull — your echo, your stress test, your lab — based on need.” As a result of the new approach centered on physician availability, physician fill rates went from 70% to 92%, meaning Mayo is optimizing its prized resource.

Across the entire patient process, results were equally impressive:

- Process steps went from 16 to six.

- Clinical care time (face time with the doctor) rose from 240 minutes to 285 minutes.

- Wait time (from request for an appointment to finishing the precare consultation) fell from 33 days to three days, a reduction of 91%.

- First-time quality (not quality of care given, but the percentage of time that all material is available to anyone, allied staff or physician, to proceed with their role) rose from 5% to 65%.

“This project has had a lot of really strong outcomes that we’ve been able to take and replicate across the division as identified best practices and better ways to work,” says Wills. The practices are being applied to 18 other subspecial clinics under a program called “Clean” (continuous lean — a continuous process or improving).

CVHC Current- and Future-State Value-Stream Maps

(Click here for larger versions of the maps)

These current-state maps were developed by CVHC staff at the start of their lean initiative and reflect the somewhat convoluted journey of a patient and information (arrow lines) as they were booked into the CVHC and their subsequent path through admissions, testing, physician visits, and, eventually, followup with referring physicians. Note that two maps (part 1 and part 2) are required to show all the process steps. The future-state map identifies the dramatic process improvements at CVHC that have occurred since lean, removing multiple steps and loopbacks. The summary boxes show an increase in clinical care time and first-time quality and a significant drop in wait time.

Streamlined STEMI

About 1 million persons suffer heart attacks each year, of which 40% die within one year (half of those die before ever reaching an emergency room). Approximately 500,000 persons suffer acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) — a severe heart attack in which an artery is blocked. When a person suffers blockage, “time is muscle,” says Dr. Ting. For every minute that the arterial blockage persists and blood doesn’t flow normally to the heart, heart muscle begins to die and permanent damage results, and if enough muscle dies, so, too, does the patient. “Every 30 minutes of delay in care corresponds to an 8% increase in mortality.”

One means of therapy for STEMI is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) — angioplasty in which a tiny balloon is expanded within the artery and a stent is inserted to keep the artery open. Less than 25% of U.S. hospitals can provide PCI 24 hour per day, seven days per week.

The challenge for Mayo and other hospitals with PCI capabilities is to reduce the time from the onset of the heart attack to PCI (time to treatment or “door to balloon”).

Reducing this time involves various process points, from the regional hospital where the patient initially presents, to the Mayo Clinic where treatment with PCI occurs, and

everything in between, including transportation. Mayo’s goal is to get the patient from initial medical contact at regional hospitals to balloon in 90 minutes. The national average is 185 minutes for patients showing up at regional hospitals without onsite PCI capability. Only 3% of patients nationally achieve a door-to-balloon time less than 90 minutes.

Prior to learning about lean, the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases had begun working on improvements to minimize delays from when a patient enters a regional emergency room to when that patient gets treatment at Mayo. “Fast Track Protocol for STEMI” was then developed by:

- Implementing standard treatment protocol using evidenced-based medicine and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.

- Applying lean and six sigma methodologies to improve clinical care processes and to reduce door-to-balloon time.

“We mapped out the process. We used lean to eliminate steps that weren’t necessary. We did six sigma to perfect each step and minimize variation, and came out with a new process. We designed a single, standardized way to treat our patients, and implemented this with all of our regional hospitals,” says Dr. Ting. During 2005, Fast Track has been implemented at 22 regional hospitals, facilities that do not have their own PCI capabilities.

Prior to Fast Track, a patient might have arrived at a remote emergency room (ER), received an echocardiogram (ECG), been diagnosed with STEMI, had transportation arranged by the regional hospital (maybe a helicopter, maybe not), transported to Mayo, admitted into the Mayo ER and their records transferred, evaluated and diagnosed by a Mayo doctor, and then finally moved to the catheterization lab for PCI. Now, says Dr. Ting, an ECG is the priority at the regional location to diagnose STEMI, and from there the “regional doctor makes a single phone call” — activating the standard protocol for treatment, activating one of three “hot load” helicopters for transportation (the engine is always left running), and activating the catheterization lab staff at Mayo Clinic.

“We’ve developed really the one, best way to treat heart-attack patients, and that’s the protocol,” says Dr. Ting. That one best way will evolve as improvements are indicated and as warranted by data, but the leaner process is driving results and saving lives. With Fast Track, the total door-to-balloon time has been cut from median 202 minutes to just 105 minutes, with streamlining occurring through:

- Door to ECG time: 18 minutes down to 5 minutes;

- ECG to Mayo activation: 44 minutes to 14 minutes;

- Activation to Mayo (transport time): 78 minutes to 54 minutes; and

- In at Mayo to balloon treatment: 62 minutes to 34 minutes.

The results of the Fast Track have attracted the attention of regional hospitals needing PCI capabilities. Mayo worked on 64 heart attack cases in 2004, and in 2005 that number rose to 240 cases. “We quadrupled of our volume because we’re providing better quality and better service,” says Dr. Ting. Consequently, that’s also created opportunities for

more research trials and more cases in which our fellows can be involved. But the most telling success of Fast Track is patient mortality rates: less than 3% via Fast Track Protocol which is better than any clinical trials results.

Developing a Lean Culture

The Mayo Clinic is unique in that “physicians and administrators partner in guiding the organization,” says. Dr. Ting. As such, many physicians and administrators have had business training and are acquainted with multiple improvement methodologies. Such is the case in the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, where Dr. Ting, Wills, Curtright, Parks, and Jim Ryan, operations manager for the catheterization lab, have led the initial lean work. Dr. Ting — who spends about 60% of his time on clinical work, 30% administration, and 10% research — and Wills attended a Lean Enterprise Institute (LEI) workshop, and followed that by bringing Guy Parsons, an LEI faculty member and president of Value Stream Solutions LLC, to Minnesota to lead four projects.

Wills says that after the first three projects were underway, the team and Parsons designed an experiential training course for the division. The program helped 25 attendees, including doctors, to identify potential lean applications and, with some assistance, work their own projects and define and drive toward outcomes, in essence, “learning to see.”

“Unlike other continuous methodologies and tools, lean does provide the opportunity to be fairly nimble and address issues and opportunities without collecting six, nine, or 12 months worth of data, and that’s what hospitals are accustomed to doing and that’s what scientists are definitely accustomed to doing,” says Ryan. “There is a ramp-up phase, but depending upon what you pick as your project and what your desired outcome is — and you’ll figure that out through your future-state mapping — some of these things are fairly quick to implement.” He adds that some provide an “ah ha moment” where bottom-line improvements are swiftly apparent, while others directly correlate to improving conditions — e.g., quality, satisfaction — that help to differentiate the clinic.

Dr. Ting is a proponent of lean, but he also understands how other process tools can improve the cardiovascular division, and he encourages staff to follow a scientific approach to consider all options: define core processes; rapidly evaluate innovative ideas that are hypothesis-driven and aligned with the strategic plan; employ a systematic approach to ensure right tools for the right situation, and then close the loop (analyze outcomes).

Dr. Ting has put together training that quickly shows the difference among process tools, such as lean compared to six sigma, and where you apply each. In addition, he explains what lean is — and is not (headcount reduction) — and a “fact or fiction” presentation quells many misperceptions by those not acquainted with lean: e.g., “lean focuses on the work, not the people doing it” (fact), “lean prioritizes the caregiving moment” (fact), “lean is going to make me work harder” (fiction).

“We’re learning to see opportunities for improvement,” says Dr. Ting. “We’re realizing that we can’t just live on the laurels that we’re excellent doctors and past accomplishments. The big challenge in medicine is that we keep saying work smarter not harder, but people are not given the tools to work smarter. It’s one thing to say work smarter not harder, but how do you get there?”

Mayo’s Division of Cardiovascular Diseases has 140 cardiologists and 700 allied staff. “It’s probably the biggest cardiology division in the country,” says Dr. Ting. “To do some of the things we’ve done, has it required everybody doing it? No. It’s the square root of N approach. If you can get that critical mass of five to 10 people that share your beliefs and are passionate about this, you can make real gains, and then hopefully spread those gains.”

For More Information

For more information about the lean work under way at the Mayo Clinic Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, please contact Dr. Henry Ting at ting.henry@mayo.edu

The Lean Enterprise Institute (LEI) runs monthly regional workshops on basic and more advanced lean tools that teach many of the concepts discussed above. LEI workbooks and training materials – all designed to de-mystify what a sensei does – show you what steps to take on Monday morning to implement lean concepts. Visit the LEI web site at www.lean.org for more resources supporting lean transformations, including the application of lean principals in healthcare.