Lean thinkers make things better by framing issues as problems, both big and small—everything from improvement challenges within the workplace to strategic goals for a company. Yet today our great challenges transcend corporate problems. The core problems confronting the entire global community call for thinking that goes beyond what we consider “Lean.”

Today it is becoming clear that earth and its resources are finite and its environment is precarious. We are consuming energy and materials at rates that will thin out our sources to near zero concentrations within decades. Of course, we discard huge volumes of hazardous materials, too. Our understanding of the dangers some of them pose is murky. As an engineer who has spent more and more time the past 25 years probing these issues, I have concluded that we are pushing the global environment to the limits of its ability to support us. We could succumb to a threat as obscure as acidifying the ocean plankton that supply half our oxygen as to rising sea levels that easier to envision.

Grumping about our situation and pointing fingers does no good. What can we do?

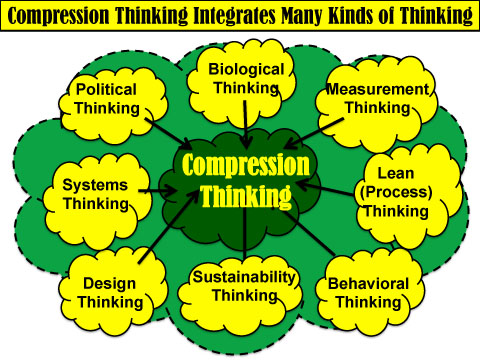

For nearly 40 years I’ve helped introduce and popularize many core ideas about quality and Lean and other modern production and management systems. And over the past five, with the help of other thinkers, I’ve developed what I call Compression Thinking.

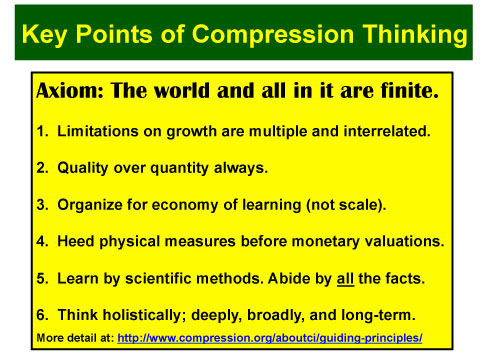

Compression Thinking builds on, and integrates powerful models such as Lean, organizational learning, and sustainability. The Compression Institute has a simple mission: Globally improve quality of life for everyone on earth, but drastically reduce our consumption of natural resources.

Compression asks basic questions about purpose in order to frame broad problems appropriately. For example, are we doing the right thing, or just being more efficient promoting our customers’ profligate consumption? We should consider many more factors covering a longer future horizon in more depth than now, and do it in less time.

Lean learning is typically confined to the purview of a company or other work organization that serves customers. Compression Thinking provokes us to question what we consider to be success. Compression challenges people to think bigger—to make decisions based on all facts from the view of all stakeholders. There is no way to escape emotion when we question assumptions, values, and habits held so deeply that we are unaware of holding them.

In this sense, we learn collectively, with other stakeholders in teams in which members have complementary roles, and whose interests may clash. That is different from working in teams to satisfy a customer that may not be in the team.

Above all, the intent of Compression Thinking, like Lean, is to accelerate pragmatic learning about serious issues and topics. It draws on lean, and other systemic approaches to respond to core challenges. It goes beyond Lean, which seldom goes so far as to question the basic motives and values of a work organization – its reason for being.

Core to our mission is finding a way curb excessive consumption and may need coaching to help us do so. Technically we know how to relieve the big squeeze. Use less and employ the R’s: re-purpose, re-manufacture, re-furbish, recycle, and so on. Emphasize quality over quantity – prevention over cure, and simple over complicated. The elements are there. Yet Compression Thinking is a huge leap in lean thinking into a very different future. It diverges from today’s economic objectives, and the usual corporate objective of lean – growing and making more money. So how can we begin to change habits of thinking, however gingerly?

Today we are working hard to identify, support, and educate companies and organizations practicing Compression Thinking. Our first steps are to identify examples of practice. In the second key point listed below, “Quality over Quantity,” we believe the scientific cleaning process illustrates progress. It’s intent is to improve cleaning in a specific locale while using much less. Scientific cleaning is now practiced in a number of universities like Texas at Austin, K-12 schools, and other public buildings, and in a few privately owned ones.

Scientific cleaning resembles Lean. First, educate janitors on cleaning for three weeks before they again pick up a rag. Clean in teams using standardized processes, equipment, and cleaning agents. Use very few cleaning agents, and no harsh ones, thereby protecting both the cleaners’ health and the environment. Use fail-safe mixing to standardize the concentrations of cleaning agents. Clean for health first and for appearance second. Elevate the work of a janitor to a more professional level, so that in practice a janitor exercises specialized knowledge that most of us don’t have.

Using scientific cleaning, the University of Texas-Austin cut water usage by about 2/3, cleared an entire building of excess equipment and chemicals, and achieved better quality cleaning. Personnel efficiency increased too, but most important, stressing total process quality over micro-efficiencies improved many other processes for the entire campus, including better-maintained facilities. The janitorial staff began reinforcing habits of conservation and recycling among the population using the buildings.

These efforts can be linked to systematic change, from the view of an industrial supplier to the scientific cleaning process, like PortionPac, which provides standard packets of cleaning agents. This company’s objective is to support its clientele’s improvement of cleaning, not to “sell more soap.” That’s a very different business model. Fees are paid for quality cleaning, not some quantity of chemical. The amount of chemical needed, and no more, is supplied as needed by a kanban system. PortionPac knows how much should be used because the cleaning process is standardized.

Indeed, the objective of PortionPac, Unger (special mop buckets), and other supplies companies is not to capture a huge market. It is to support an ever-improving cleaning process by the coalition of facilities managers that use scientific cleaning. Few users are private companies. One can speculate why. Purchase-price-variance incentives induce purchasing managers to buy more stuff and haggle prices down, and to close their eyes to the benefits of better quality cleaning to the entire organization.

While generalizing from these early cases can reach too far, it’s important to see how these ideas apply beyond one player in the system. Compression Thinking emphasizes process improvement on integrated processes that make communities more resilient and that improve quality of life. That is well beyond single company improvement and differs from concentrating on markets. Separate companies being successful in their own markets does not translate into overall process improvement in any community. This mental reductionist trap is similar to that of thinking that if every machine in a production process is independently more efficient, the effect will surely add up to greater overall efficiency of the total shop.

Vigorous Learning to Improve Quality of Life

Thirty years of Lean have proved that it has enduring value. Yet today’s challenges demand an approach that stretches Lean and other disciplines into unexplored integrative territory – a great melding. Definitions of waste that attach primary value to physical material, as in manufacturing, need amending. In most cases value added is not intrinsic within the material, but depends on the product’s function in use. Or more broadly, human value is in a process that improves human lives, and in most instances physical products merely enable that process. And the definition of waste has to shift to how nature sees it, not only how a customer would see it.