My family and I bought a house in 1991 just after The Machine That Changed the World was published. As we were moving in, the previous owner, knowing a bit about what I did, asked if I would be interested in an odd book he had recently found in a flea market. It was Ford Methods and the Ford Shops, a First Edition printed in 1915.

I had heard about this book (some of it is cited in David Hounshell’s wonderful study, From the American System to Mass Production, and we had used the material second-hand in Machine.) But I had never actually seen the book and I had somehow imagined that it was the book version of extinct.

I accepted the book, of course. And once I found a spare moment, I opened Ford Methods and entered a whole new world. I had thought that there were two acts in the lean drama – mass production as exemplified by General Motors (incorporating Ford’s production methods at the massive Rouge complex into a modern management system) and lean production as pioneered by Toyota. But I quickly learned that Henry Ford had been the first systematic lean thinker, pioneering what he called “flow production”, and that much of what Toyota had done was built directly on Henry’s shoulders, by-passing GM and mass production. I also learned that much of what Ford had pioneered had been lost in the move to the Rouge complex, which was the only Ford production system I had known.

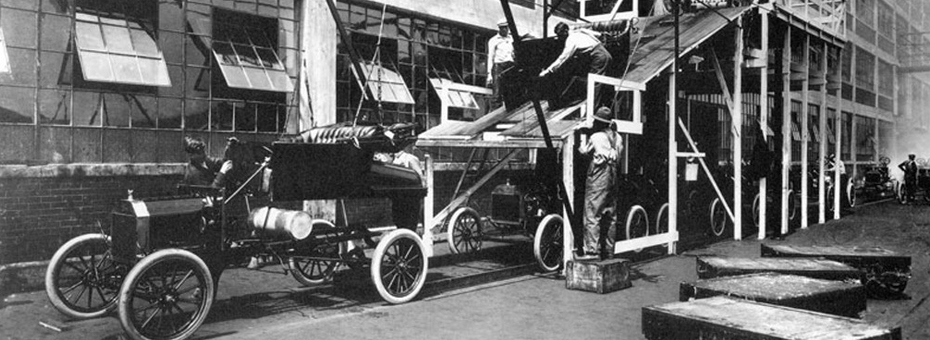

I recently revisited Ford Methods and the Ford Shops since this past spring was the 100th anniversary of an amazing moment of innovation when Ford and his colleagues brought together all of the elements of a pro-typical lean production system. We all know about the powered, moving assembly line but this step actually came last, in the spring of 1914. It was the culmination of a series of innovations after the introduction of the Model T in 1908, including consistently interchangeable parts (made possible by the Ford gauging system with go/no-go gauges for every part, which were shared with every supplier), standardized work to a precisely repeatable cycle time, line-side supply of materials in small amounts frequently, cells for component fabrication with machines placed in process sequence and little or no WIP between steps, and a crude pull system for materials flow to regulate production in the upstream processes.

The leap from the previous world of stationary assembly with fitting (filing) of parts to the correct dimensions, treasure hunting for materials and tools, and extensive rework at the end of the process was remarkable. In final assembly at the Highland Park, Michigan, plant (where these leaps were made) Ford achieved a 900% jump in labor productivity between 1913 and 1915. The leaps were not so large in all of the component areas (only 300 to 400%!), but the sum of the innovations was to reduce the cost of what was then one of the world’s most sophisticated manufactured products (the Model T) to a level that a wide spectrum of the population could afford. Thus the modern consumer economy was born.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Ford Methods and the Ford Shops is the extraordinary level of detail Ford allowed authors Horace Arnold and Fay Faurote to describe: The entire bill of material of the Ford car, the sequence of steps involved in producing every component, every piece of documentation used to manage Highland Park, the layout of every building with the location of every machine. This was the first example in the Lean Community of fully sharing experimental findings and I only wish we would be as transparent today.

If you have a spare moment for a trip to a different world—one that will spur your thinking about your own challenges today—you can find copies of a reprinted version of Ford Methods on Amazon and other sites. However, if you want to gain the full effect with vastly better photographs, you should go to Bibliofind or some other out-of-print site to get the First Edition. If you do, perhaps I will run into you wandering the now empty halls of Highland Park.