How prepared are you to respond to crises? And what core lean practices bolster your organizational muscle to pivot successfully? This 2016 roundup on jidoka shares key ideas that can help you boost operational resilience and boost your organization’s ability to tackle new challenges. Lean thinkers will discuss this challenge during the upcoming VLX session on Leading Through Crisis starting October 19.

Build quality into products or inspect it in at the end of the line? Put your machines to work for you or be a tool of them? Seek problems constantly or always hide them and pass them down the line? Such basic questions—contrasts—are woven, as it were, into the very thread of TPS when one examines the key role of jidoka.

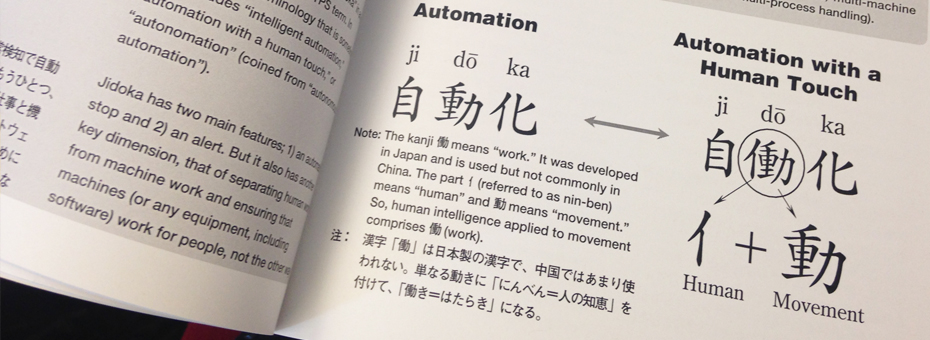

What is this relatively unknown element of lean? As Toyota notes in its material on TPS, “The term jidoka used in the TPS (Toyota Production System) can be defined as ‘automation with a human touch.’” To get a thorough understanding of jidoka, there’s perhaps no better resource than the book Kaizen Express, which describes jidoka as “providing equipment and operators the ability to detect when an abnormal situation has occurred and immediately stop work to institute countermeasures.”

Jidoka is necessary because it “enables operations to build in quality at each process and to separate operators from machines for more efficient work.” Kaizen Express elaborates that, “Jidoka has two main features; 1) an automatic stop and 2) an alert. But it also has another key dimension, that of separating human work from machine work and ensuring that machines (or any other equipment, including software) work for people, not the other way around. Jidoka refers to the characteristic of work to have the ability to detect any abnormalities and stop itself so as not to produce defects.”

The book says Jidoka is necessary because it “enables operations to build in quality at each process and to separate operators from machines for more efficient work.” Doing so frees operators from having to monitor their machines, and releases them to spend time on other value-creating work.

Like so many methods developed as part of TPS, there are layers upon layers of detailed practice beyond a simple “stop at every defect” approach.” To understand how jidoka extends into detailed work in everything from machine setup (reduction) to ways of loading and unloading parts, read chapter three of Kaizen Express.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of this idea to the practice and history of lean. As Toyota recounts on its company site, the word traces its roots to the invention of the automatic loom by Sakichi Toyoda, Founder of the Toyota Group. In 1896, Sakichi Toyoda invented Japan’s first self-powered loom called the “Toyoda Power Loom.” He later invented an automatic loom with the ability to identify defects as they occurred (such as a thread breakage), shutting down the loom so that the problem would be dealt with immediately. “Since the loom stopped when a problem arose, no defective products were produced. This meant that a single operator could be put in charge of numerous looms, resulting in a tremendous improvement in productivity.”

Jidoka captures the principle of building quality into the production process—of designing work so that the people making the product have the means and mindset to be constantly vigilant for what is okay and what is not. By attacking waste at the source, jidoka starkly contrasts with an unfortunately-too-common approach of hiding flaws, passing them down the line, and relying on someone else to fix problems far from their source. Again, from Toyota’s own materials: “Jidoka illuminates the causes of problems by stopping the equipment exactly as it is when a problem first occurs and by calling attention to the problem immediately with a signal lamp or some other kind of indicator.”

Such an approach is both a technical practice and a pure expression of how one values the role of people in the production system. As Taiicho Ohno notes in Toyota Production System, “Stopping the machine when there is trouble forces awareness on everyone. When the problem is clearly understood, improvement is possible.” There may be no greater contrast in TPS and modern corporate behavior than this simple idea.

Over time the practice of jidoka extended beyond the use of one machine, one production line, one factory; Ohno extended this “autonomic” (automation with a human touch) idea to the entire business organization:

“At Toyota, we began to think about how to install an autonomic nervous system in our own rapidly growing business organization. In our production plant, an autonomic nerve means making judgments autonomously at the lowest possible level; for example, when to stop production, what sequence to follow in making parts, or when overtime is necessary to produce the required amount.”

“These judgments can be made by factory workers themselves, without having to consult the production control or engineering departments that correspond to the brain in the human body. The plant should be a place where such judgments can be made by workers autonomously.”

Today, despite its primary role in TPS and lean, jidoka is far less known than other core practices. In this excellent thread, Art Smalley notes that despite it being the core idea of TPS, jidoka receives a tiny portion of the attention given to concepts such as just-in-time. And yet it merits greater attention, he argues.

Jidoka captures the principle of building quality into the production process—of designing work so that the people making the product have the means and mindset to be constantly vigilant for what is okay and what is not.Smalley explains that jidoka’s emphasis on tackling problems through careful analysis when they happen, where they happen, highlights other key lean ideals: “This ‘go and see’ attitude and ability to get to the root cause of problems is a fundamental part of Toyota’s success over the years. One of the biggest differences I see between Toyota and other manufacturing companies is this ability and discipline to both see problems and to continually probe in order to get to the root cause of the problem. Without this sort of mindset and skill level I think it is difficult for any aspect of Lean to succeed or really sustain over time.”

In this terrific interview with Tomo Harada, Art reveals the effect that this approach has on how people approach their work: “The overall thinking behind Jidoka is the practice of making hidden problem obvious. If a problem remains hidden then it will never get solved. You have to bring problems to the surface and cause people to respond to them in order to get at the root cause.”

Indeed, many of the common associations that lean has today (as a Thinking Production System, as a community of problem-solvers) trace back to the vigorous practice of jidoka as it evolved over time. Coupled with other dynamics of TPS, jidoka supports a complete system designed to support learning through the work at hand. As Michael Balle notes (about jidoka) in How Does Pull Relate to Problem-Solving?, “The pull system is the greatest production teacher you’ll ever have, but you have to be ready and willing to learn what it teaches.”

Today we see the end result of this approach, but should always remember that what started as a way to liberate operators from their looms has emerged as a key to supporting people in making ever better things. As Art Byrne explains in How One-Piece Flow Supports Quality, “One of the key ideas in lean in any setting, manufacturing or non-manufacturing, and which one-piece-flow supports, is that you build quality into the product at every station in the line as opposed to trying to inspect quality at the end. It’s a simple and powerful shift in how people think about their work. Never pass a defect down the line.”