One comment on Jeff Liker’s recent Lean Post about Tesla brought up the notion of people saying “[we are] different, we make no cars, we can’t apply TPS.” If you’ve tried to introduce Lean in a setting outside of the automotive industry, you’ve likely heard the complaint of “we’re different” (as I blogged about back in 2009).

It can be true that “you’re different” while the implication of “therefore, Lean doesn’t apply here” is, at the same time, false. It’s unfortunate, and it slows down progress when people frame the discussion as “we’re different” instead of asking, “How can we apply (and adapt) these approaches to our organization?”

In healthcare, we’ve all heard statements “patients aren’t cars” and “a hospital is not a factory.” (I’ve written about this before, too.) These statements are factually correct, but Lean has been proven to help in healthcare (as in many other settings).

I’ve been fortunate to take three trips to Japan with healthcare executives, physicians, and Lean practitioners from around the world. We visited Toyota, other factories, and a few hospitals that were on their Lean journey.

One required stop, in Nagoya, is The Toyota Commemorative Museum of Industry and Technology.

As you walk through, you see artifacts like the Toyota “AA” car that was first produced in 1936:

This car is located about mid-way through the museum. Why is that? The first part of the museum covers Toyota’s early corporate history, starting with being founded by Sakichi Toyoda as “Toyota Automatic Loom Works, Ltd.” in 1926.

So what did Toyoda, the company, do for 10 years before their car was produced? Go back and read that again… “automatic loom works.” What’s that?

You can also see a short video I shot of one of those looms in operation a few years back.

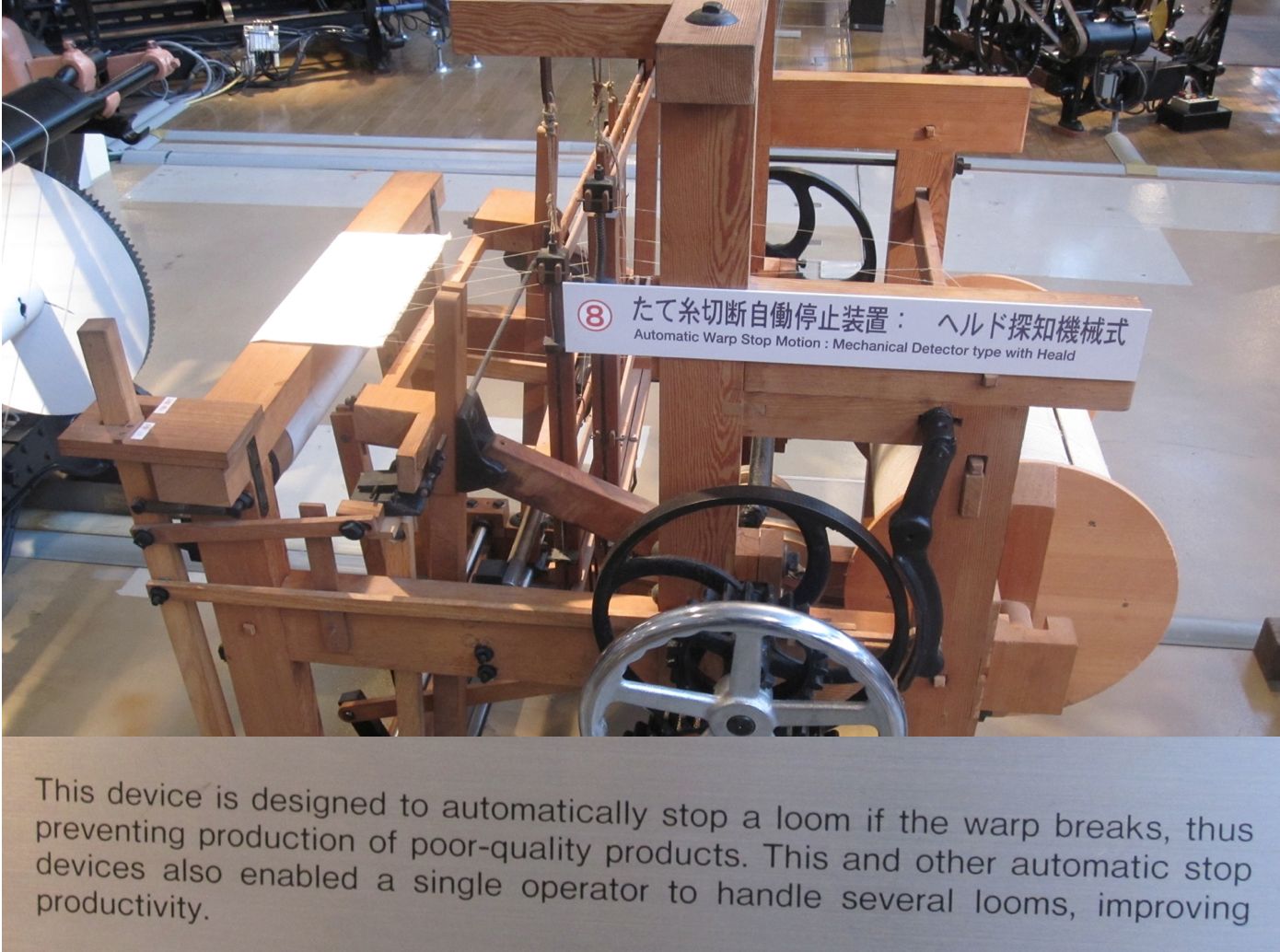

The amazing thing that you learn (and see demonstrated) is how the “Type G” loom, from 1924 was designed to stop automatically when it detected a broken thread. Here is another photo of one of those looms:

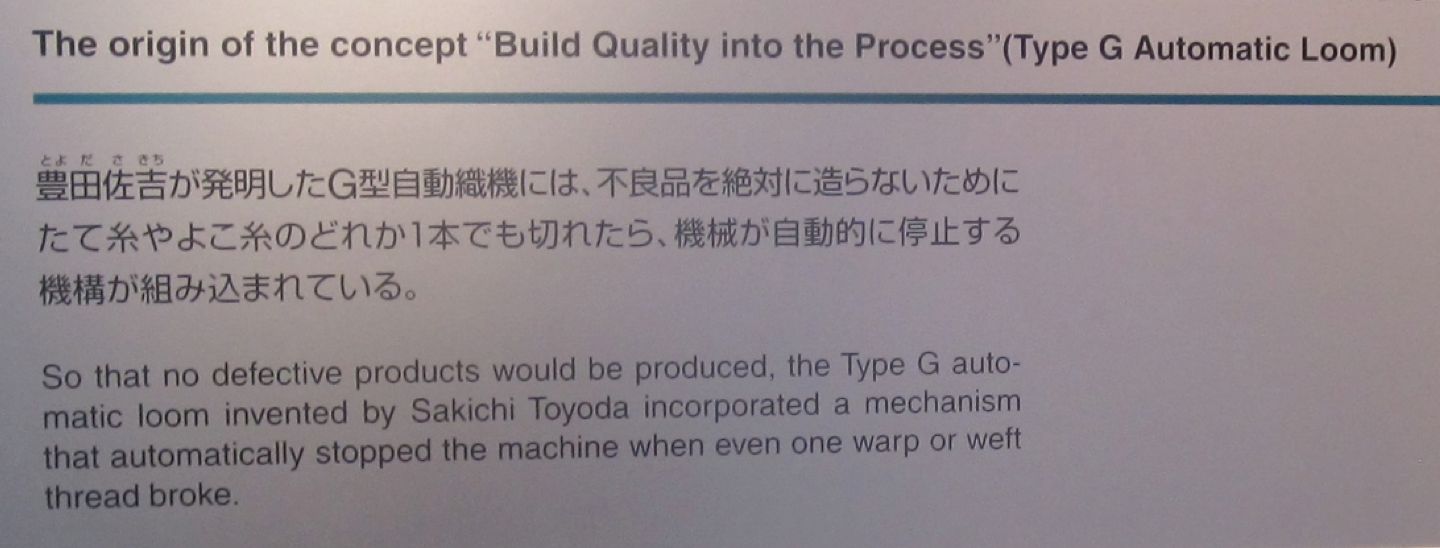

So, this is the origin story for the concept of “jidoka” or the idea of built-in quality, as their sign explained:

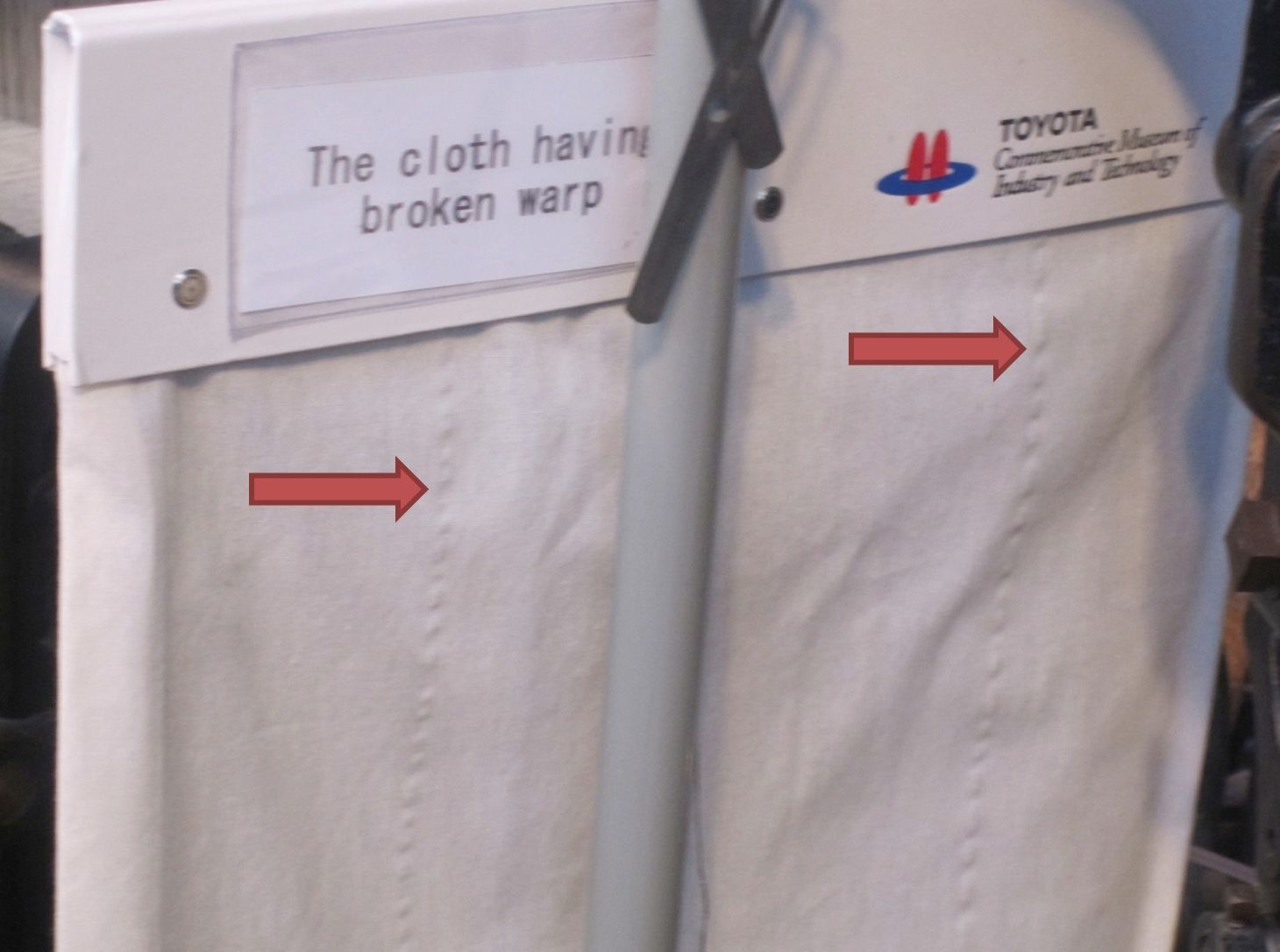

We might also call this “error proofing” and it’s an early example of stopping production when there is a quality problem. If the machine didn’t stop automatically, it would have to be attended to by a worker. There was a one-to-one ratio of workers to looms because they had to manually watch and stop the machine when the thread broke. Otherwise, a defective cloth would look like this (with two runs marked by the red arrows):

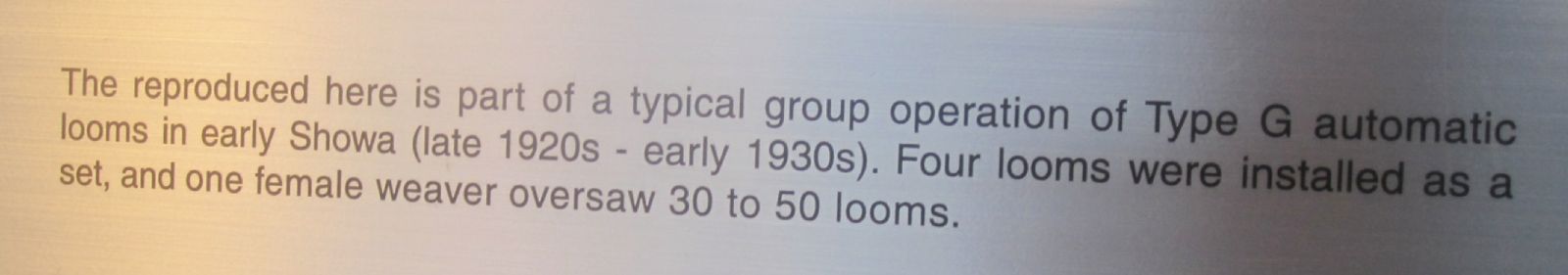

In modern Lean and TPS, we often talk about “person-machine separation” meaning that a person isn’t stuck just watching a machine run. The innovations of the Type G loom allowed much greater productivity, as a worker could “run” or monitor “30 to 50 looms.”

All of these TPS and Lean concepts were created prior to 1936. It has always made me wonder if the newly-formed Toyota Motor Company had some people who looked at the lessons from Toyoda Automatic Loom Works and then said, “But we’re different! We don’t make weaving looms!”

Yes, cars are not weaving looms. Patients are not cars, either. Airplanes are not cars. Electric vehicles are not the same as internal-combustion engine vehicles. We can play that “one of these things is not like the other” game all day long. A better use of time, perhaps, is to think about how TPS concepts and high-level Lean management principles can be adapted to your own setting.