To all the coaches out there, have you considered your methods and which ones to use when? Watching the women’s world cup the past few weeks, I’ve noticed a number of different coaching styles and tactics–from yelling to observing, arm-waving to arm-folding, walking to sitting. But what might lean coaching look like? How can we help our employee-worker-learners to develop capability as they navigate problem situations in their work?

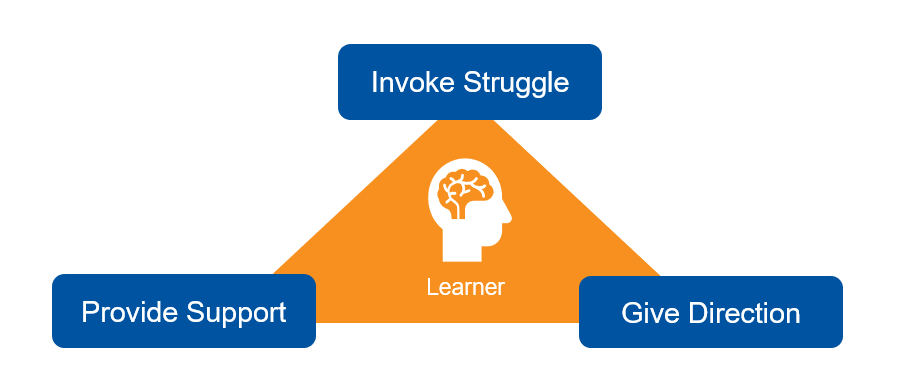

Recently Mark Reich and Laura Mottola, two senior coaches with distinct backgrounds (Mark comes from manufacturing in Toyota and Laura from engineering and the mining industry) developed a coaching triangle intended to reflect the different sides of coaching in general and the methods of A3-style coaching more specifically.

Mark & Laura worked with a team of coaches in NYC recently to help talk them through this triangle and to consider where their practice currently exists, where they would like to be, and where they have the greatest weakness.

Perhaps the biggest aha of the day came when a coach realized that he must apply more than just one coaching tactic, sometimes even for the same learner working through the same problem situation.

While each method represented in the triangle may appear straight-forward, the coaches also realized that they invoked struggle more than they originally thought. Upon further reflection they produced a list of reasons why it might be useful to invoke struggle with one’s employees:

- People learn via mistakes

- It provides a window into people’s capability and mindset (they mentioned the roles of Porter & Sanderson in Managing to Learn)

- It puts responsibility (or ownership) on the learner

- It promotes new habits

However they questioned: “What is the difference between providing support and giving direction?” Mark and Laura shared how providing support could mean helping an employee implement an informed countermeasure (similar to this example from Veada) whereas giving direction might tell someone where to go next in their problem investigation. Similarly, Laura shared how she provided support when conducting a gemba-walk with a manager.

Laura and Mark also provided advice for these specific coaching challenges:

Where should I begin?

With A3 coaching, the natural place is to begin where the learner is. Like everything else in lean, this is a situational approach. So how do we know where the learner is in terms of their capability or attitude towards problem solving? The book Managing to Learn provides us with a great scenario we can all learn from. Sanderson does not assume that he needs to “direct” Porter up front. He offers up the opportunity to solve the translation problem. Porter’s first draft then clearly reveals Porter’s capability to Sanderson. So the place to begin is for the coach to learn the task at hand–which is how to develop the A3 learner. The challenge then is: what coaching approach to take.

How can I maintain focus & patience without jumping to conclusions?

This really doesn’t have to do with focus and patience. It has to do with an acknowledgment that the answer or solution that you might have for the problem may not be based on the facts of the situation. There is no need to show patience. As a coach, go and see for yourself, with or without your coachee, what the facts of the gemba tell you. Do this quickly, with urgency. You can’t “persuade” someone to answer with what you think you know based on assumptions. A huge fault in poor A3 coaching.

How can one foster passion about the problem?

Passion comes from ownership of the problem and the desire to solve it to improve the situation. Often this is tied to the specific situation of the learner solving the problem. If that person can make this problem better, it helps their work. Who doesn’t want that? But they may have struggled in the past to solve or at the least mitigate this problem. Your role isn’t merely to ask them the right questions, but rather to foster capability, support them, and understand the problem with them, to help them overcome the issues they have faced in the past. It’s a lot like sports coaching. You have responsibility to dig into the problem with them and help them overcome it. You can’t do this by reviewing their A3 in a conference room.

How to demonstrate value in the process of A3 problem-solving?

The value comes through solving the problem and seeing the result for the individual and the company. If you are not progressing towards that goal, you should reflect on your coaching. This is what we are trying to teach in our workshop “Coaching to the Challenge”. You can’t coach distinctly from the business problem to solve. Each business problem has its unique set of urgencies. This HAS to be part of the coaching process to determine, in this case, if you should “Invoke Struggle”, “Provide Support”, or “Give Direction”.

How to know what resources or direction to send mentees?

You have to look at the problem as if it was your problem to solve. Taiichi Ohno famously said, “Provide an assignment to your Team Member as if it was your problem to solve”. Study the “gemba” (whatever that is) of the problem yourself. This doesn’t mean you should tell your mentee all you learn. But it provides much better judgment on what to tell. Without question.

What data is important?

Again, to quote Mr. Ohno, “Data is important, but I rely on the facts”. It is too easy to sit at a desk and ask for data. Having said that, in many situations, the problem can be measurably defined with some kind of historical data. The data should help us understand the weight of the problem. Is this a big issue or small? Does it deserve our attention as a company or not? Is it trending negative or not? But to truly understand the problem and consider root causes and countermeasures, we cannot rely on data alone. Must go and see.

What data is accurate (and how to know)?

Go and see is the only way. Data is often not accurate.

How to keep it practical (not theoretical)?

The quicker we can go and see and try some quick countermeasures, the more we can keep it practical. There is really no other way.

How can one remove ego and feeling “I’m right!”

This is hard to do. The Team Member may feel that as you are delving into the problem, you are invading their space, taking away their ownership of the work. So your diligence to learn together with them is key. And you must demonstrate for them that you can be helpful. The role of the coach is much more challenging than the problem solver. You have to ensure the work gets done (solve the problem) AND develop the capability of the Team Member to solve problems on their own.

How to encourage Gemba-based study?

Take them there. That’s it.

How can one find time to engage with the mentee and the problem regularly?

Set specific milestones for the Team Member. Before a coaching session ends, ask him/her when they feel they can complete what has been assigned. If it seems slow, you should advise. The schedule should be determined by the business urgency. Ask in the moment to set a time to meet again based on the next step of investigation.

How can I create an environment for conversations?

Suggest to the Team Member that he or she should speak to specific people to get input on the problem they are working on. The more valuable inputs from invested stakeholders that the Team Member can hear, the more validation/confirmation he or she can have that the path is correct. This will open up the dialogue. Of course, conversation opens up if you can guide the individual to investigate the problem themselves and own it. The more you ask factual questions around the work and the less you ask judgmental questions, the more conversation will happen.

How to reinforce the value of root-cause analysis & learning?

Root cause analysis is a learned skill. In many A3s, the logic is not clear and assumptions are built into the root cause. Such as: “lack of a standard or training program”. This type of response is merely a solution disguised as a root cause. Good root cause analysis requires a deliberate study of the gemba. But if this is accomplished, the problem will be eliminated and will not come back.

How to think objectively about the problem?

The facts allow us to think objectively. Making the problem measurable is also critical. So we need data and facts from the gemba. Otherwise, it is just our opinion. This is sometimes difficult as we think we already know the problem when in fact we don’t.

How do I know if I’ve done enough (as a coach) and the next step to take?

Two things – first, seems like a no-brainer, but has the Team Member solved the problem? This can be a false positive, if you’ve simply given step-by-step directions to get the answer. The second important point is whether the Team Member has progressed in his or her thinking to be able to solve problems on his/her own, with less support. This is hard to measure, but speed is one way. Problems should get solved faster using this methodology.

—

What do you think? Is there value to these three different methods? Do you tend to use one more than another? Are there any pitfalls you have learned from experience?

We’d love to hear from you.

Seasoned? If you are already a seasoned coach, take your practice to the next level and learn more about this triangle at the upcoming Lean Coaching Summit,

New? Or you can learn about the context of coaching and A3 management by taking any of our courses on Managing to Learn: 2-day workshop in Boston, August 27-28; or our online class September 9-October 7