Dear Gemba Coach,

A major assumption in lean thinking (unless I’ve got it all wrong) is that people genuinely want to do a good job, and the only thing standing in their way is a poor system. In other words, it’s the assumption that most people have high inner motivation. But some (well, probably many) organizations act on the assumption that you can’t really trust anyone to do their job unless they are constantly controlled and scared into complying. It’s hard for me to see how lean can help any org without changing this assumption first … or?

Interesting … and a very old debate. Since we’re talking about deep assumptions, let’s take a step back and try to see where these assumptions come from.

Back in the XIXth century, Max Weber, a founding father of German sociology studied the large organizations that were appearing in his time and defined an ideal “bureaucratic” model – bureaucracy in a good sense, not in the sense of “red tape.” The ideal organization, he thought, would be characterized by:

- Roles: A rigid division of labor where everyone’s duties and tasks are clearly defined.

- Rules: Impersonal regulations to establish a chain of command, processes, and compliance.

- Merit: Hiring people with specific skills corresponding to their roles and promoting them by their merit up the chain of command.

At the time, this vision had two huge benefits. First, it was scalable, and in a period of growing colonial empires, it meant that you could copy-paste the model everywhere fast. Second, it protected functionaries from the arbitrariness of princes. Blue-blooded power simply couldn’t do quite as it wanted (as it used to) because of established roles and rules.

And, let’s face it, this bureaucratic ideal (Weber recognized its flaws and how it could devolve into red-tape bureaucracy) led to massively successful organizations. The drawback, of course, was that it was slow, cumbersome, and inefficient in many ways.

The One Best Cola

Enter Frederick Taylor. At the same time, on a different continent, an American engineer observed operations at large bureaucratic businesses, such as Midvale Steel, and concluded that most workers were not working as hard as they could – they would “soldier on,” which is do the minimum to keep the boss happy. In a brilliant application of bureaucratic thinking, Taylor then divided the roles of designing the job, which he allocated to engineers, and doing the job – what workers were supposed to do. He then established very precise rules about how the job was supposed to be done for maximum efficiency. And he enforced compliance through both piece-rate wages – which did raise significantly worker’s intake – and boorish management. At the time, this was thought of rewarding merit, since only the “best workers” would agree to follow the Taylor system to the letter throughout the day.

Pepsi is sweeter than Coke. The best way to draw attention to this feature in order to sell Pepsi is to do blind tests: make people sip of a thimbleful of Pepsi or Coke without knowing which is which, and they prefer Pepsi. Drink a full glass and most people prefer Coke.

Similarly, Taylor demonstrated his system at exhibitions and so on, and over the course of a day, the productivity improvements were staggering. However, as the system got implemented for real in factories, the drawbacks in terms of worker overburden soon became apparent and generated resistance, both from worker unions and academics – which was to become the “human relations” school.

Taylor’s business card read: “Consulting Engineer – Systematizing Shop Management and Manufacturing Costs a Specialty.” To a large extent many consultants still operate on the same premise: let me show you radical productivity improvement by having an expert redesign the process, and then you can figure out how to scale it.

All this to say most of our large organizations hold four built-in assumptions about efficiency:

- Design the right boxes to specialize activities, making sure roles and rules are clear.

- Seek productivity improvements for each of these boxes by improving output per person by having experts optimize the process rules.

- Enforce compliance through the chain-of-command by incentives (get a bonus if you comply) and pressure (you’ll see what happens if you don’t) – and now IT systems.

- Promote the best enforcers.

The pessimistic theory that you can’t really trust anyone to do their job unless they’re constantly controlled and scared into compliance is really a consequence of these four instructions. Clearly, other than in very specific, repeatable environments, there is no reason to believe the optimized process will help staff deal with specific local conditions. Clearly employees have learned to do their jobs and keep their heads down and negotiate the system – so, unavoidably, the leaders who subscribe to this theory are always facing “execution” issues and quite naturally draw Taylorist conclusions of people “soldiering” and the need to command them more harshly and control them more strenuously. Besides, since the people who obtain the most compliance get promoted, this set of ideas tends to dominate boardrooms.

Meanwhile, in Japan

On yet another continent, in Japan, something else was going on. Sakichi Toyoda is considered the Japanese Edison. Born in the time of the samurai, he was a polymath inventor obsessed with perfecting the automated cotton loom (his mother used to work at a wooden loom and, son of a carpenter, his first innovation was a change that allowed for an easier shuttle movement). As he built and lost several loom companies (trouble with banks is not new), he was mostly obsessed with two topics:

- Improving the looms to make them easier to operate,

- Improving productivity in loom assembly.

Early Toyota engineers were constantly on the lookout for what was going on in the loom manufacture business and very well aware of Taylorism’s productivity promise. Indeed, the term that we know as “kaizen” (change for the better) probably stabilized in the early XXth century to translate productivity improvements.

But, somehow, in his travels to the U.S., Toyoda also came across a copy of the first “self-help” book ever written, titled, funny enough Self Help by Samuel Smiles, a Scottish iconoclast. I’ve read the book and it’s a long list of examples of exceptional people achieving exceptional success in every industry by “pushing character,” by pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, and through talent and hard work, becoming innovators. The book’s main themes are upward mobility through self-education – no wonder it touched Toyoda.

But, somehow, in his travels to the U.S., Toyoda also came across a copy of the first “self-help” book ever written, titled, funny enough Self Help by Samuel Smiles, a Scottish iconoclast. I’ve read the book and it’s a long list of examples of exceptional people achieving exceptional success in every industry by “pushing character,” by pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, and through talent and hard work, becoming innovators. The book’s main themes are upward mobility through self-education – no wonder it touched Toyoda.

Toyoda spelled out his company philosophy in the following guiding principles:

- Always be faithful to your duties, thereby contributing to the company and to the overall good.

- Always be studious and creative, striving to stay ahead of the times.

- Always be practical and avoid frivolousness.

- Always strive to build a homelike atmosphere at work that is warm and friendly.

- Always have respect for spiritual matters and remember to be grateful at all times.

What we’re seeing here is a very different set of assumptions than “soldiering on.” Toyota culture was built on constantly looking for people that set out to defy expectations through self-study, creativity and always trying to stay ahead of times – what I see as the “paranoid optimism” that pervades the company.

“An engineer should wash his hands three times a day” is not just folklore, but the firm belief … that solutions come from the shop floor, by drawing out the understanding and ideas of everybody.The Toyota we know was essentially the work of Sakichi’s grand-nephew, Eiji Toyoda, and, in the few interviews we have of him we can see that he sees the company as the sum of systems internal leaders developed and got adopted (Taichi Ohno’s Toyota Production System being one such, but far from the only one). For instance, during a study trip to Ford factories in the U.S. in the fifties, Eiji Toyoda recalls he was flummoxed by all the statistical quality talk in English but came back with a leaflet for a suggestions program – he saw the value of this right away – and had it translated and implemented upon his return, setting up Toyota’s still living creative ideas system.

“An engineer should wash his hands three times a day” is not just folklore, but the firm belief passed on from Sakichi Toyota to his son Kiichiro the founder of the car company to their heirs to this day, that solutions come from the gemba, the shop floor, by drawing out the understanding and ideas of everybody.

The Kanban Trick

As one point, this led Toyota to a very different notion of productivity. They realized that maximizing output at every station didn’t make much sense if the next process wasn’t ready to process the work. With the kanban trick, they hit upon the idea that productivity really was “making the demand with fewer resources” – an idea that would have far-ranging consequences, to this day. They also realized that to achieve this, the granularity of problems they had to solve was so small, engineers would never do this on their own, and it meant working far more closely with the operators themselves:

From: productivity by increasing output on existing resources (or adding investment)

To: productivity by keeping the same output but making work easier through eliminating waste (mura, muri, muda) and reducing the need for resources

This doesn’t mean that Toyota is not a large bureaucratic company, with its share of rules and compliance – it’s a bureaucracy like any other automaker. What it does mean, however, is that Toyota leaders are taught to look for something else than enforcers – people who can think for themselves, be creative (creativity, challenge, and courage – the three Cs) and inspire others to follow their lead.

(As an aside, although the vaunted Prussian armies were supposedly a caricature of the bureaucratic model, a dissident part of general command realized after being defeated repeatedly by Napoleon they needed to develop a cadre of autonomous officers, with competence, initiative, and leadership – sadly for us, the rest is history.)

In terms of assumptions, Toyota developed a different set of instructions to look for efficiency:

- Clarify the challenge by going and seeing at the gemba,

- Find someone ready to tackle the challenge with initiative and ingenuity,

- Task them to find workable solutions with the people doing the job themselves,

- Support them in dealing with the bureaucratic constraints of the organization,

- Change the organization step-by-step when need be.

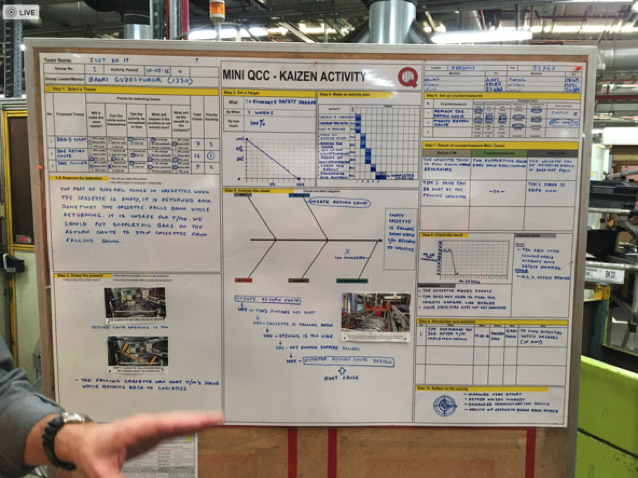

Typically, so see this thinking all over Toyota’s gemba, whether in hoshin kanri, A3s or on shop-floor kaizen:

Although Toyota clearly has many features of a large bureaucracy, it’s also confusing for an observer because roles are never that clearly defined (indeed it’s hard to figure out what one person’s real function is), there are many technical standards but organizational processes vary greatly from plant to plant, and people are promoted on a weird mix of having cracked difficult problems, being supported by the people they managed, and having convinced their bosses of their potential.

Seek New Thinking

Apologies for the long background. Now to your question – do we need to change leaders’ attitudes before we consider lean?

Well, that seems a rather high barrier to pass. Rather, we could take a page from Toyota’s set of instructions and look for leaders who are already convinced there is a better way, are keen of finding out how but don’t quite know how to go about it.

Many of the leaders I know that do well in lean know from experience that people can’t always be trusted to comply (and why should they?) but also want to create an organization built on mutual trust. They are looking for a way to do that.

With this as a starting point, lean makes a lot of sense as there are many tools to help you, such as:

- Listening to customers to figure out the boundary conditions of OK versus Not-OK in varied use situations,

- Setting up a kanban system to see where resources should really be applied and help people see the next step in the process as customers, not enemies,

- Establishing team leaders to learn and teach problem-solving (as gaps to standard) and support teams during the day,

- Support kaizen efforts to look for smart ideas and committed people, and recognize and reward progress.

- Learning, through hansei, from the previous tools and rethinking the challenge, the organization, and the distribution of who does what accordingly, so that people see leaders are trying to make things better for frontline employees.

We’ve learned in lean that you act yourself into a new way of thinking rather than think yourself into a new way of acting. So, from kaizen to kaizen, leaders learn to spot their wrong reactions based on the old assumptions and deliberately try to encourage trust and initiative. It’s never easy, and it’s never done, but it does transform organizations in the process.

To sum up, first understand the challenge (what are the assumptions you want to change), then chose the leaders you want to work with (those who are ready to change their assumptions in practice to create a trust-based environments), practice the lean tools on the gemba and support leaders in spotting their old thinking when it comes out, and seek new thinking, one kaizen at a time. Never easy, never boring and, surprisingly, much, much quicker than one would think – if the motivation is right to start with.

Lastly, if we take at face value Sakichi’s final injunction to always have respect for spiritual matters, we can recognize that most human beings look for inspiration and direction. This is why we read (and post) positive slogans on LinkedIn, read books, journals, or browse the internet. We’re always on the lookout for a good before/after story, in the hope that things can improve and move beyond what we currently know. This, in essence, is the spirit of kaizen at the very core of lean. Lean is not for everyone, but it’s the best method we know for the leaders who recognize that spirit and seek to build systems that will support and sustain it.