Most large companies use assessments to support their lean work. They monitor if you are using the various tools of lean or performing the activities of lean through formal surveys asking yes/no questions on items such as:

- Are kanban systems in place and being used to control inventory?

- Is 5S apparent throughout the facility?

- Are standardized work documents complete, up to date, and being used to control how work is done?

- Are daily huddle meetings being held across the facility?

In some cases, these assessments are numerical, for example, assessing the percentage of processes using kanban to control inventory. Some are done by outside lean “experts,” while in other cases, they are self-assessments. Regardless, I typically see them being conducted as part of a mechanistic attempt to control processes. Trying to assess your way to lean mechanistically generally fails in achieving high-performing lean systems.

View Lean as a Sociotechnical System

By contrast, Toyota views the Toyota Production System as a sociotechnical system. The company realizes that the primary point of lean tools is to surface problems, highlighting the difference between the actual situation and the desired situation. Kanban, for example, are attached to containers, with the number of kanban reflecting the number of containers circulating. If you are running out of parts, the kanban make this problem visible immediately. Or, if you have a full supermarket that gets down to below your level of safety stock, you also realize that you have a problem. That is when problem-solving should kick in to understand the standard and the current situation and try out ideas to get closer to your standard. Simply discovering whether or not you have a tool like kanban throughout the operation tells you little about whether it is being used effectively for some defined purpose.

Toyota realizes that the primary point of lean tools is to surface problems, highlighting the difference between the actual situation and the desired situation.I witnessed a mechanistic approach to assessment when I was invited to teach a large corporation about lean product development. There, I first met with the vice-president of continuous improvement, who reported directly to the CEO. He told me his tale of woe. Earlier that year, the CEO contacted the president of Toyota and asked for help teaching his company TPS. He apparently expected a study mission to Japan. Instead, Toyota’s president replied that he was sending the top expert on TPS to train them at the gemba for one year. The CEO vowed to treat the TPS sensei with honor and ordered the VP to do whatever he said.

The TPS sensei arrived and reviewed their progress to date. They had been going hot and heavy with lean for several years. The VP proudly explained that they had created a lean production system model, a training program, and an annual assessment of all production sites and that the site leader’s bonus depended on a good score.

After listening quietly, the TPS sensei gave his first instruction. “Stop doing that, especially the lean assessment tied to the bonus. We do not want leaders simply complying,” he said. Instead, they were to select a site, and he would go to work developing a model line to demonstrate real TPS.

I listened intently and was not surprised by any of it. I had done my best to explain that they were using a mechanistic approach viewing TPS merely as tools to implement. The sensei saw lean as an organic system that penetrates the culture. He wanted them to see lean done right in at least one place before charging off to implement stuff they did not understand. While the VP was grateful for my insights, he admitted that he was continuing to do the lean assessments because he had many plants to transform and couldn’t wait for the sensei to get around to broader deployment.

It was clear that this VP saw lean as tools to implement and assessments tied to rewards as a core tool. Why? The simple answer is he was trying to mass-produce lean. The easiest way to get broad deployment is to teach the tools and then hold leaders “accountable” through metrics and targets. Do it or else! This approach fit his mechanistic mindset that the organization is a machine to be redesigned and transformed by implementing lean tools.

He was thus missing one of Toyota’s most important insights. Toyota realized that lean is a sociotechnical system driven by people. Much of lean is focused on the work that people do. And practicing lean mindfully and on purpose requires competence to carry out the work, drive to do one’s best possible, and the skills to improve on how the work is done. That comes mainly from intrinsic motivation—a sense of purpose, not compliance.

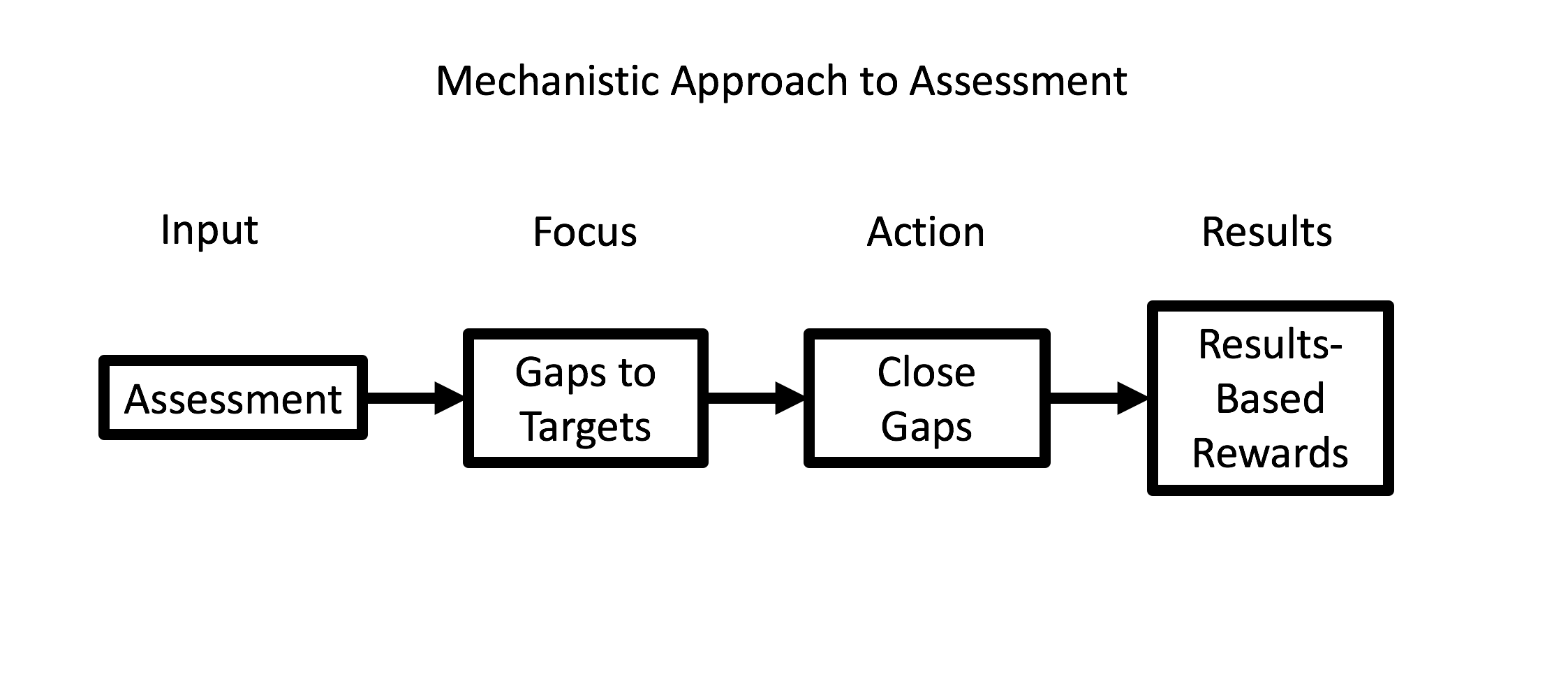

The underlying mechanistic model of assessments looks something like figure 1 below.

You assess, identify gaps to the targets, managers then implement to close the gaps, and the results determine their rewards or punishments. Failure to hit your targets may result in punishment like withdrawing the annual bonus. Pavlov, here we come!

Motivation Should be Viewed as Intrinsic (not Extrinsic)

What is wrong with this approach? First, as the Toyota sensei suggested, it views the motivation of the manager as extrinsic—despite the significant evidence that when we comply based on extrinsic rewards, and our hearts are not in it, we do the minimum necessary to get by. What Toyota wants in its management is passion, commitment, innovation, and perseverance—something that author Angela Duckworth calls “grit.”

Second, the model assumes that every site should look exactly like the lean model, that everyone should focus on these presumed desirable features. Yet different sites face different situations. There is no guarantee that simply implementing a tool like kanban or visual management will lead to the desired results, or, if it does, that the processes will be sustained.

Third, this approach provides no vision or direction. The direction is simply to close these gaps. It fails to strive for something needed by someone like the customer or the business or the associates.

And fourth, implementing lean tools to close the gaps implies these are the solutions we need to our problems. These targets are established before we have tested this hypothesis, meaning that we are committing to solutions at the point of maximum uncertainty.

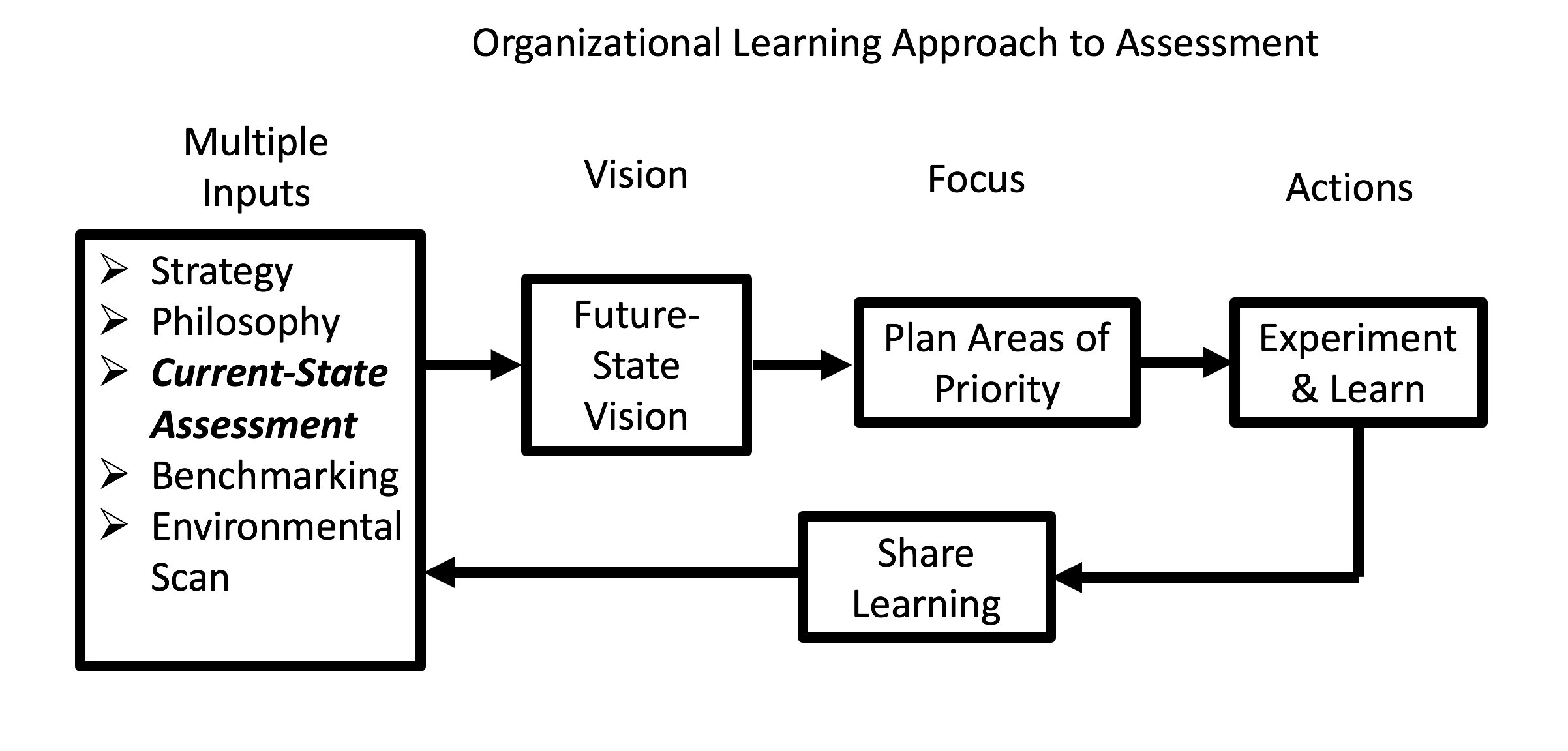

The approach Toyota strives for is better represented in figure 2.

Toyota aspires to be a learning organization where each unit strives to meet challenges that are aligned with the strategy and philosophy of the company. The company’s overall direction is developed and then broken down to the challenges of each business unit. The business units develop a vision of where they need to be to support the company direction. They then break this down level by level, so there are aligned objectives and plans. Benchmarking and assessments can provide useful How can we reach our stretch objectives? By expecting the unexpected. We do not know what will happen until we try something. Only then can we learn and adjust.information inputs to the vision. Once the direction is clear, the assessment has done its job. Now the focus is on working towards it.

The action stage is not one of “implementing lean solutions,” but rather exploring through the zone of uncertainty. How can we reach our stretch objectives? Expect the unexpected. We do not know what will happen until we try something. Only then can we learn and adjust. “Experimenting” is a better image for this than “implementing.” Experimenting suggests that hypotheses are sometimes wrong. A mechanistic perspective sees failure as, well, failure—something that should be punished (or at least not rewarded.) This mindset limits us to a safe zone of solutions that we are confident will work.

If we are truly seeking innovation, we need to encourage experiments—an approach to discovery where things either work out as we hope or where what we learn does not support the hypothesis. In both cases, we are learning, which is positive and should be encouraged.

We share what we learn with others who may benefit from it. That does not mean sharing best practices to be copied by others but sharing both successes and failures that might be inputs for vision and planning.

Of course, some ideas might help us solve nagging problems right away. We may have hit the wall on improvement and need to get associates involved. Perhaps through my book or a benchmarking visit, you might get ideas for how to better engage your associates. It could be through some form of quality circles, a team leader role, daily management meetings, or using kata to develop scientific thinking.

Rather than race off to implement something, broadly think through the purpose. What are we trying to achieve? Look at your current condition. Pick an area where you can pilot the idea and learn before going live. Experiment and learn!

What to Do Next:

Advance your career and enhance your team’s ongoing learning by subscribing to the Virtual Lean Learning Experience. With an Annual Enterprise Subscription, you can deliver a full year of unlimited access to seminars, practical exercises, and on-demand recordings of all VLX presentations to everyone at your organization.

Individuals who register for the Annual Single-User Subscription gain the same benefits for themselves. The next seminar starts June 21, 2021. Learn more and subscribe.