O.C. Tanner at a GlanceBusiness: Develops employee recognition and rewards programs

|

If you’re an employee at O.C. Tanner and you spot a problem on the job, you’re in the right place.

Problems and problem-solving, you see, are O.C. Tanner’s specialty. The Salt Lake City-based manufacturer of corporate awards has focused the company’s culture on problem-solving. Ideas are so welcome that even those viewed by some higher-ups as totally unworkable receive not only a hearing, but an engineer may try to put them into practice.

The goal, here, of course, is not to try things that fail, but to ensure that every idea gets serious consideration as a way of proving the company is dead serious about getting employees to pitch in with their brains to improve processes.

And make no mistake, O.C. Tanner knows exactly what it’s doing. After two decades of practicing lean concepts, this is one outfit that knows what works, and from experience, what doesn’t.

O.C. Tanner’s process improvement journey has enabled the company to achieve some impressive overall gains. For instance, in the past it took 26 workdays for the company to go from the launch of an order in the plant to shipment of the finished product. Today that process takes one hour. During the same time, Tanner has more than tripled production output with the same number of people.

As with many a lean journey, O.C. Tanner’s experience came replete with challenges. One of the biggest was engaging the workforce– and keeping them engaged– in solving problems. There were some employees who thought the lean effort might actually damage the company. Others felt management should do the problem solving while they did the work. But Tanner persisted, continually trying new approaches for getting people to work as hard with their brains as they did with their hands on the production line.

Hiring the Right People

“After 30 minutes of observing, we know who we want to hire, and we know it’s a good fit.” |

In fact, just to get in the door here, you’ve got to prove your mettle as a problem-solver. If you can’t do that, you’ll never get a job at O.C. Tanner. “We are very concerned about who we hire — in fact, we added only eight people last year in production,” says Gary Peterson, executive vice president for supply chain and production and the company’s lean champion from day one. (Read a Lean Leadership Series Q&A with Peterson about how he changed his management behavior and how O.C. Tanner coaches people to develop their problem-solving skills.)

Following an initial pre-screening by a temporary employment agency, applicants looking for employment with O.C. Tanner must surmount a group hurdle with a handful of other applicants. The group of would-be O.C. Tannerites are placed in a room together and charged with a process problem that, in effect, is insoluble– that is, the process itself is faulty, and the number of products that need to be made can’t possibly be produced in the time allowed.

“They do this exercise as a group, and they forget they are being interviewed,” Peterson explains. “Some get frustrated, others clam up. But some people light up and are encouraging others to come up with a solution. After 30 minutes of observing, we know who we want to hire, and we know it’s a good fit.”

O.C. Tanner’s means of enlisting every employee in search of better ways of doing work doesn’t end with hiring. The company has a number of ways to sustain lean thinking and behavior, from regular kaizen meetings to a deeply entrenched daily process of soliciting and following up on ideas using a card-based system.

Clearly, garnering employees’ trust and ensuring them that every employee’s ideas are valued is key. “We want to encourage the ideas, and show that we’re here to support those ideas,” adds Tolan Brown, director of the Tanner improvement system (TIS), the company’s own flavor of TPS.

Although Peterson remains, in effect, the company’s de facto lean guru, a year and a half ago Brown took over his role as head of TIS, when Peterson was named EVP. “If you tell teams or individuals that an idea can’t work, they’ll shut down,” Brown asserts. “If what they suggest is a failure, you have to let them see that it’s a failure and help them try something else. People have to feel empowered to try new things.”

Problem-Solving Factory

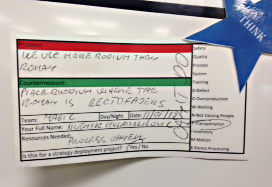

The centerpiece of O.C. Tanner’s approach to problem-solving is the red/green card. On the surface, it seems like a simple enough mechanism– a worker sees a problem with a process, or detects a particular need that, when filled, could make that process better, smoother, faster, or less costly. The worker fills out the card, describing the problem, and if possible, offering a potential solution, and then pins the card to the team’s board. Each week the team meets and decides which problems to pursue. Most get solved by the team, but if the solution requires outside support, the team takes the card to engineering, or to a process owner for assistance.

|

| A red/green card showing a problem in red and a possible solution in green. |

On any given day there may be a handful, or a dozen, or more cards on the board, awaiting the attention of an engineer or process designer. Instead of telling the employee who generated the idea why it won’t work or isn’t feasible, engineers will either try to build and implement it, or if not, they’ll go back to the suggesting employee to obtain more information on how the proposed solution could be adapted so that it could work.

Management doesn’t track how many red/green card-based ideas are submitted and ultimately adopted, but Peterson says the company regularly surpasses its six-month savings goal of $2 million, and recently boosted that target to $2.25 million as a result.

O.C. Tanner also encourages daily problem solving by workers through “team huddles” in which production staff get together three times a day to discuss any issues that may have arisen and possible solutions. For instance, if an order requires a large volume of pins or emblems, team members can be shuffled to adjust to production requirements. In another daily problem-solving activity, the previous day’s returns and root causes are discussed, with solutions evaluated to keep them from recurring.

A Clear Mission

Besides its success as an idea factory, one of the cornerstones of the O.C. Tanner lean effort is the company’s clear purpose. “We are in the business of valuing others,” Peterson says succinctly. “Our view is that if we are in the appreciation business, then we have to live it. It’s really inculcated in the culture, and it has made it easier to do lean.”

A big piece of O.C. Tanner’s mission is to build high quality products for its customers, who nearly all come from the ranks of the Fortune 500. Most are household names, including some of the biggest corporations in America. Last year the company shipped just under four million awards representing 2.7 million orders. Obviously, with this level of clientele, slipshod quality isn’t going to cut it.

Ideas to Cut Waste, Boost Quality

While the river of red/green card ideas and potential solutions represents the firm’s idea lifeblood, teams of employees perform numerous formal kaizens targeting specific processes. Some are aimed at reducing waste, while others focus on quality.

For example, Paul Terry, VP supply chain, cites the case of a perplexing shortage of gold held in inventory. O.C. Tanner uses a fair amount of gold each year in thousands of pins, rings, and other award items. Thus the company needs to maintain a stock of gold on hand — enough to manage its current orders, but not so much that the company is tying up huge amounts of money simply holding the precious metal in inventory.

“We asked our people to come up with ideas that could explain the discrepancies,” Terry adds. Team members suggested that the scales may be fluctuating, or that they might be inaccurate. “We experimented with new scales, and we found that our old scales didn’t go to enough decimal points to ensure accuracy. Also, it turned out that the scales were subject to vibration and breezes coming in the work area, and they weren’t adequately anchored. The result was that the weighing system wasn’t registering the right weights.”

Using these findings as a guide, the engineering staff tried out various solutions. Ultimately, they built a metal pedestal that was bolted to the floor, with a granite top on which the scale sits, with windshields protecting it from air movement. As a further step, the company’s IS people created a system eliminating manual transactions when quantities of gold were transferred from the vault to production. The overall solution put an end to the gold inventory discrepancies.

Other recently overhauled processes are plating and the dark antique polymer process. Plating was targeted for a kaizen due to high levels of internal defects, machine downtime, preventive maintenance hours, and operating costs. The plating improvement team was charged with determining the root cause of each problem area and finding a way to improve that outcome.

The team traced much of the quality trouble to problems associated with the automated machinery. The end result was that the plating process was converted from an automated line to a manual process in which the operators could more carefully control quality. Among the gains from the switch to manual were:

|

First-time quality |

78% to 99.5% |

|

Machine downtime |

3,351 hours/year to 37 minutes/year |

|

Preventive maintenance |

140 hours/year to 5.5 hours/year |

|

Parts cost |

$21,747/year to $2,224/year |

|

Inventory cost in machinery |

$839,652 to $108,964 |

The dark antique process, requiring the application of a black lacquer to an emblem prior to polishing, was marred by one of the highest internal defect rates in Tanner’s production area. After polishing, the emblem is washed, but the black lacquer sometimes peeled off, causing an internal defect that had to be reworked at additional cost.

Not surprisingly, the dark antique process previously had been the target of earlier improvement initiatives that elevated first time quality to 88% and later to 98%. Nonetheless, the 2% defect rate still placed the dark antique process at third highest on the internal defect report.

Finally, in its latest attempt, the process improvement team created a black lacquer process that eliminated the need for a black polymer or lacquer on the surface of the emblem. Instead, emblems now receive a black plating resulting in an attractive finish with no defects.

Yet another work routine that cried out for fixing was the wash/steam process. Once an emblem or ring was nearing completion having been polished and buffed, the wash/steam process was necessary to remove any remaining polishing/buffing compound. “After collecting six months of quality data, we saw that the process had a 64% defect rate,” Peterson says.

“We designed and built the ‘next generation’ wash/steam machine using a more simplistic, manual approach that improved quality, efficiency, and delivery.” Machine downtime fell from 363 hours per year to zero, while losses due to ruined electronic boards also dropped from $3,200 per year to zero. Similarly, rework cost plunged from $27,990 annually to zero. The total cost savings attributed to the change from automated to manual wash/steam totaled $86,954.

From Batch to One-Piece Flow

Before adopting lean practices, the company, ran the business based on a batch manufacturing model. Customers who want recognition emblems, trophies,or bejeweled gold pins with their company logo first work with O.C. Tanner’s design staff to agree on a design for the award prior to placing an order.

During the batch era, orders were placed and O.C. Tanner’s production area churned out products in volume — all built at its sprawling 570,000-square-foot facility in Salt Lake City. Typically, a large corporation would call and order 500 award pins and the company began churning them out in volume. Each batch took its turn going through the various manufacturing processes, from fabrication, to plating, cleaning, polishing, buffing, and so on.

“A lot of people told us that lean was not going to work for us, because they said it was for repetitive operations, and everything we make is made to order– it’s all unique.” |

Peterson, who was assigned to spearhead the effort to make the company a more efficient enterprise, had learned a thing or two about lean in college. He was eager to try out his ideas for process improvement. One of the first things he did was to begin experimenting with cellular manufacturing, or what he refers to as “mini-factories.”

From the get-go, he knew he was facing an uphill slog, if only because O.C. Tanner is a custom manufacturer or job shop, with products made to order. “A lot of people told us that lean was not going to work for us, because they said it was for repetitive operations, and everything we make is made to order– it’s all unique.”

Nonetheless, one of the first things O.C. Tanner did was to take a worker from each of the various functional production units, and assemble a mini-factory.

The first attempt at a mini-factory was a bust, Peterson recalls. “They picked people who were the best at each function,” Peterson says. “They were good at the skills, but not so good at the people skills. The people we interviewed for the next mini-factory team had ideas for improving the processes and they worked well with others. That experience told us we needed to be hiring a different type of person.”

But the change didn’t come without pushback. “People were fighting it so hard initially,” Peterson says. “I thought the reason was that they just didn’t like change. But then it occurred to me that they thought lean was wrong and would hurt the company.”

Workers were realigned into teams and asked to help solve problems. “People thought solving problems was management’s job,” Peterson says. As a result, the company changed its approach to compensation, instituting a “no raise” policy for those who refused to participate in finding problems and proposing fixes or improvements.

Things changed quickly as a result. With the wind suddenly behind the lean effort, the company abandoned the “pay for problem solving” tack, shifting course toward skills-based pay, with everyone expected to have three to six different skills. “So we started paying for job skills, and the only way you could get a raise was to add skills.”

The company designs its machines for flexibility. “All the heads fit in every machine. And all the machines are on wheels, so they can be moved wherever needed.” |

It wasn’t long before the plan got too expensive. Workers were adding skills so fast the cost quickly overran the compensation plan budget, Peterson says. “We said there was a limit to how much you can learn. And the employees said to forget the pay for skills idea, but they wanted the job skills anyway to be effective in their work. So we dropped the job skill pay plan.”

Today, the emphasis is much broader. “Now we pay for the employee’s overall contribution, including problem-solving, making things happen, and influencing their team.”

Along the lean journey, the company made it clear that lean was the only way the wind was blowing, and they had better catch it if they wanted to stay aboard the O.C. Tanner. When creating new mini-factories, Peterson says, “We knew efficiency would double. So we told people, half of you won’t be here when this change is completed. We will hire the best 15 people we can find. Then we waited until another 15 left, and we built the next mini-factory.”

In this way O.C. Tanner was able to effectively trim the workforce in production without resorting to layoffs. Adds Terry, “We didn’t lay off people, because we didn’t want people to view the lean transformation as a way to reduce staff.”

Paperless Routing System

Supporting the mini-factories is the company’s own paperless routing system, called LIDS, for “Lean Information Delivery System.” It consists of a rubber cup with an embedded electronic chip programmed with each of the different work processes that must be performed on a particular customer order.

Each time a worker is ready to perform a process, such as plating, the worker takes the cup, inserts it into the machine at a particular work station, and immediately the text in a 5 by 6-inch screen over the work station describes exactly the work to be performed by the operator with that machine on that product, whether it’s a pen, emblem, pin, or trophy.

|

|

An emblem award in a rubber cup with an embedded chip programmed with the work processes that must be performed on a customer order. |

The LIDS system facilitates the movement of workers from process to process as they are needed, because it allows a worker to leave a product at a work station and move elsewhere to perform other tasks, while another worker can then come along and finish the original piece simply by picking up the cup and moving on to the next station to perform the next job required for that product.

If a bottleneck occurs at a particular machine, workers can shift to another machine to perform the same work, or they can move to help out a team that is short a worker. Employee cross-training in the various process skills — enamel, setting, polishing, plating, etc.– is so popular, in fact, that Tanner uses kanban cards to allocate training. When a training slot opens, the team with the opening decides how to allocate the training kanban card, i.e., which skill they need the most, and who should receive that training.

An employee who wants to learn how to do plating posts his or her card in a queue, and when a training slot to learn plating opens up, it gets filled by the next person interested. Worker flexibility is a clear enabler of O.C. Tanner’s lean effort, facilitating the smooth functioning of one piece flow as customer orders shift each day.

For each customer’s order, the processes required are identified and the tasks in each process move sequentially, with each process having a prescribed takt time. However, with O.C. Tanner often working on different clients’ orders simultaneously, the production times may vary depending on the complexity of the product design. For this reason, Peterson says, “The next step for us in our lean journey is likely to be organizing products into families, so that for a family of products, we will be able to pull at the same rate for each client.”

Machinery Made Here

O.C. Tanner is somewhat unusual in that the company builds all its own process machinery and tooling. In other words, if a buffing team worker sees a need for a new machine that promises to eliminate a step or improve quality in the buffing process, the engineering group will build the machine and install it on the line in the mini-factories.

|

|

Racks containing thousands of cutting heads that are retrieved for reuse when customers call. |

The engineering department also makes the trims and dies — basically operating heads — for the various machines on the line. Each head must be different to meet the unique needs of each customer order. The company maintains a library containing an estimated 100,000 finished trims and dies, each identified with its own barcode. Having these on hand enables O.C. Tanner to immediately begin production of a reorder whenever a regular customer calls and wants more pins, emblems, or medals for an upcoming awards program.

The company designs its machines for flexibility. “All the heads fit in every machine,” Peterson points out. “And all the machines are on wheels, so they can be moved wherever needed.” He relates how a production group awaiting his approval to move an entire line from the second floor to the first floor of the main building grew frustrated waiting. They finally set aside a lunch hour and went ahead and moved the entire line. Peterson cites it as an example of empowering people and showing them you trust them.

Attitude Adjustment for Management

Speaking of culture, it took some coaching, but the top managers who report to Peterson admit they had some attitude adjusting to do to get their own minds around the lean way of doing things. “It took me a while to get my head around some of these approaches to management,” Brown says. “I came from a more autocratic, top-down culture at a high-tech company. I realized my job was not to solve all the problems myself, but to teach people to solve those problems. It takes some discipline not to solve everything yourself.”

|

|

O.C. Tanner managers on a strategy alignment gemba walk through the production area are (left to right) Dave Siebert, vice president, order fulfillment; Dave McKee, production manager; Gary Peterson, executive vice president, supply chain & production; and Harold Simons, former executive vice president, manufacturing, (since retired). |

Terry echoes that view. “In the past, people looked to the managers to solve the problems,” he says. “It used to be that as a manager, director, or VP, people expected you to be the answer person. Probably half or more of our managers were entrenched in this thinking. As a leader, you have to be able to accept the idea that you don’t have all the answers.

“Today I view my role more as that of coaching and developing people, giving them opportunities to grow,” Terry adds. “Now we are asking the employees, what ideas do you have that can help us solve problems?”

Keep learning …

- O.C. Tanner develops employee recognition strategies and rewards programs that help companies appreciate people who do great work.

- Join 110,000+ fellow lean practitioners who subscribe to LEI’s weekly newsletter for the latest in training, books, and examples of lean transformations. Subscribe today.

- Visit the LEI book catalog for workbooks and books with how-to information.

Learn more about problem solving at these workshops:

- Lean Problem Solving

- Problem Solving to Align Purpose, Process

and People (2 days) - Coaching for Lean Problem Solving