Be among the first to get the latest insights from LEI’s Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD) thought leaders and practitioners. This podcast was delivered to subscribers of The Design Brief, LEI’s newsletter devoted to improving organizations’ innovation capability.

A decade-long MIT D-Lab project to develop and improve a mechanized thresher with subsistence farmers in Tanzania helps produce rice, wheat, maize, beans, millet, sorghum, sunflower, pigeon peas — and engineers.

The transformative multi-grain thresher (MCT) dramatically boosted farmers’ threshing productivity, turning what used to take two to three weeks of manual labor into hours of mechanical work. Developing and improving the MCT over the years also boosted the capabilities of student engineers, who collaborated on-site with farmers to understand their needs and environment before applying design and engineering principles.

“The D-Lab experience was eye-opening for me and others,” said Elliot Avila, who, as an MIT student, led a D-Lab team that developed an MCT prototype in 2013. “For some people, it gives the perspective that we can all be engineers and innovators. For me, it exposed the human element of design and showed me that engineering can address social issues. It changed how I wanted to be an engineer.”

(Source: https://www.imaratech.co)

The MCT replaced traditional labor-intensive local methods of separating grain from a plant by flailing stalks on the ground or having cattle walk over them. Approximately 80 percent of Tanzania’s 67 million people are small-scale subsistence farmers, cultivating plots of less than three hectares, mainly for their consumption rather than commercial markets.

Significantly, the MCT also minimized crop losses and damage during harvesting. The higher quality crops commanded higher prices, improving incomes and economic stability.1

The MCT’s versatility and portability were key design features resulting from farmer-student collaborations. The versatile thresher effectively processes nine crops commonly grown on Tanzania’s small farms.

Its portability – one will fit on the back of a bicycle or motorcycle – was a significant development that spawned a new business model in local agricultural value streams: entrepreneurs buy MCTs to offer mobile threshing services to nearby farms, thus generating new jobs and income.

Participatory design and lean product and process development

Through D-Lab classes, MIT graduate and undergraduate students work on teams with community partners in developing countries to design and engineer low-cost technologies that alleviate poverty. Founded in 2002 by Amy Smith, a senior lecturer in mechanical engineering, D-Lab’s first class established the program’s hallmarks: hands-on, project-based, and real-world. Smith, who holds SM and ME degrees from MIT in mechanical engineering, was named by Bloomberg Businessweek to its 2010 list of the World’s Most Influential Designers.

The D-Lab experience was eye-opening for me and others … it exposed the human element of design and showed me that engineering can address social issues.

D-Lab now has 20 courses with 12-15 offered annually. Instructors have taught more than 4,000 students how to apply engineering and design principles through participatory design. D-Lab identifies three types of participatory design:

- User-centered design uses inclusive practices when designing for people living in poverty.

- Co-design engages in effective co-creation when designing with people living in poverty.

- User-generated design builds confidence and capacity to promote design by people living in poverty.

“Participatory design is not a silver bullet,” according to the D-Lab website. “There are times when it can be more costly than other approaches. However, when participatory design is the appropriate approach, we advocate for taking the time to include the people who are facing the challenge that the innovation will address” to develop more sustainable and relevant solutions.

The approach aligns with the six core principles of lean product and process development (LPPD):

- Put people first: Organize your development system using lean management practices to support people in reaching their full potential and performing their best.

- Understand before executing: Understand your customers and their context while exploring and experimenting to develop knowledge.

- Developing products is a team sport: Maximize value creation by leveraging a deliberate process and supporting practices to engage team members across the enterprise from initial ideas to delivery.

- Synchronize workflows: Organize and manage the work concurrently to maximize the utility of incomplete yet stable data so that you achieve flow across the enterprise and reduce time to market.

- Build in learning and knowledge reuse: A development system that encourages rapid learning, reuses existing knowledge, and captures new knowledge builds a long-term competitive advantage.

- Design the value stream: Make trade-offs and decisions throughout the development cycle based on what best supports the future delivery value stream to improve its operational performance.

“I wouldn’t use some of the phrasing of LPPD but there is alignment in principle,” said Avila, who now is director of Imara Technology Company Ltd., a nonprofit spinout from the MCT effort that manufactures, markets, and services the threshers in Tanzania.

Understand before executing

Development of the MCT traces back to 2008 when a D-Lab team introduced Tanzanian farmers to a pedal-powered corn sheller developed in Guatemala. Resembling a stationary bike, the machine had a wooden seat with a sheller on the side. Farmers fed cobs into the sheller’s opening while someone pedaled. The machine stripped kernels from cobs into a bucket and ejected bare cobs backward.

But the machine cost about $200 and weighed over 100 pounds, so farmers couldn’t easily afford or transport it. Moreover, it required dismantling used bikes, which are valuable to Tanzanians. Back at MIT, the team designed and built a simple, lightweight, hand-cranked, $30 sheller that fits on the side of a bike. The sheller was an improvement but it processed only one crop and hardly closed the “technology gap” faced by small-scale farmers in Tanzania.

A World Bank report on Tanzanian agriculture in 2024 noted that “only 25 percent use animal tillage and up to 10 percent use mechanized implements.

“Tanzania’s economy, like that of many other Sub-Saharan African nations, is heavily reliant upon agriculture and the smallholder farmers,” according to the D-Lab website. “The vast majority of these smallholder farmers face a technological gap; because modern agricultural machinery is prohibitively expensive for them … .” A World Bank report on Tanzanian agriculture in 2024 noted that “only 25 percent use animal tillage and up to 10 percent use mechanized implements.” 2

Field research in various regions of Tanzania that Avila did during a 2013 D-Lab project revealed that farmers needed a machine that was robust, affordable, efficient, portable, and capable of processing multiple crops, especially the staples of rice, wheat, maize, beans, millet, sorghum, sunflower, and pigeon peas. The team also collected data and comments from farmers and other potential customers to refine functional requirements such as throughput speed and beater design before fabricating a prototype.

After graduating with a BS in mechanical engineering in June 2014, Avila continued prototype development with a D-Lab Scale-Ups Fellowship, which connected graduates with investors and helped them develop business models before launching companies.

Customers and context

During field trips with a prototype in 2015-2016, Avila observed how farmers interacted with the machine, talked to them about their needs and work environments, and gauged market interest. Some potential customers expressed interest in renting machines. And most prospects preferred to make a down payment and pay off the balance over time.

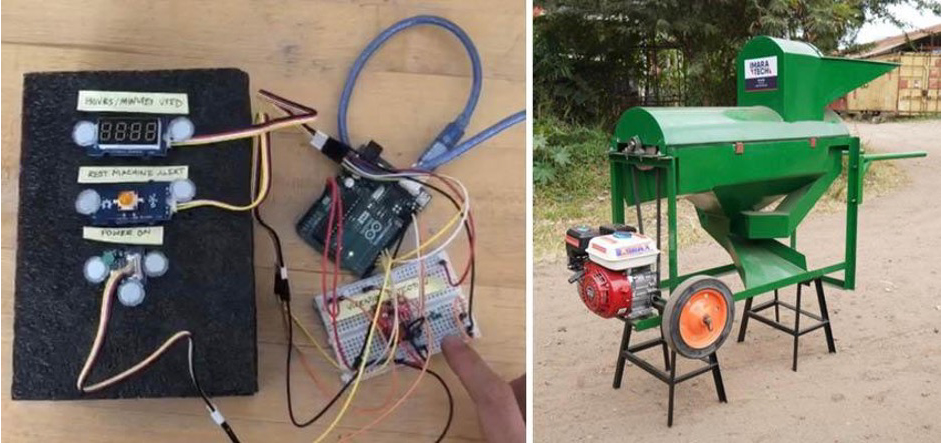

What began years before as a pedal-powered maize sheller had developed into a gas-powered, six-horsepower, wheeled thresher that processes a variety of local crops and fits on the back of a bike or motorcycle.

On a research field trip, he met a farmer who owned a massive tractor and maize sheller, purchased 30 years ago solely for his 50-acre maize farm. The size of his farm justified mechanization larger than an MCT but most farms in the area were small.

Next, he met with several farmers who had formed a cooperative group to help each other thresh their maize over several days by beating it with sticks. They paid each other with a day’s worth of food or liquor. Unlikely MCT customers, these farmers would benefit from a lower-cost bicycle-powered or handheld maize sheller.

A nearby third farmer offered a potential market to target initially. He grew pigeon peas and maize on two farms, totaling less than five acres. To do all the threshing in one day at harvest time, he paid a group of sheller operators who serviced local farms.

While the farmer couldn’t afford an MCT, the entrepreneur operators who serviced several farms could. This model benefited the end-customer farmer and the thresher operator/owner, and a local workshop that made and sold the shellers for $400, a price competitive with imported Asian shellers.

(Source: https://www.imaratech.co)

Development as a team sport

The observations and conversations he had with farmers and other potential customers helped “paint a clearer picture of my target user and the environment in which the MCT will operate,” Avila said in a 2015 D-Lab blog post. “The finished MCT hit the specification targets users cared most about: sells for about $1.1 million Tanzanian shillings (about $500), uses a liter per hour of fuel, and can shell or thresh 10 100-kilogram sacks of grain per hour.”

To operate threshers, farmers toss plants into an entry chute that leads to a chamber where a rotating drum beats and tumbles stalks to separate them from the grain. The thresher expels large pieces of chaff out one end while grain and smaller chaff pieces fall into the machine’s lower section and out a chute. A blower removes the small pieces of chaff, leaving clean grain.

What began years before as a pedal-powered maize sheller had developed into a gas-powered, six-horsepower, wheeled thresher that processes a variety of local crops and fits on the back of a bike or motorcycle.

Designing the value stream

The initial focus on entrepreneurs who sell threshing services to small-scale farmers meant that the MCT value stream did not just sell machines; it sold small businesses. Avila’s customers would need a marketing strategy as much as he did. To build both – and the MCT threshers — he incorporated Imara Tech in 2017. The company now directly employs 10 Tanzanian staff in production, sales, and back-office operations. Avila describes his current role as an adviser who supports a Tanzanian business partner who runs the company.

… we have a lean, flexible manufacturing network that creates machines on demand.

Thresher sales come primarily through farm equipment dealers, often family businesses located in market towns. Imara Tech provides display units and marketing materials to dealers. The company uses radio advertising to reach potential customers before harvest season and it demonstrates threshers at markets with bank finance officers present.

“Radio advertising is great,” Avila said, “but it’s so much more powerful when you follow it up with a market demo run next to someone from the bank saying, ‘sign up now to get a loan.’” The company offers a one-year warranty and increasingly partners with non-governmental organizations that offer training and financing to youth and women prospects. “The most important thing that we can do is offer a quality product at an affordable price that delivers opportunities for people to earn income,” Avila said.

A key selling point for prospective customers is not that the MCT is 75 times faster than traditional threshing methods but that the work it does generates up to the equivalent of $12 per hour, multiple times higher than an average daily wage in Tanzania, he noted.

D-Lab students helped build the Imara Tech team’s capability by running training sessions to enhance the skills of local engineers and technicians, empowering them to take ownership of production. This knowledge transfer was crucial for scaling the thresher technology.

Manufacturing happens in the Imara Tech facility in the industrial zone of Arusha. “We regularly outsource jobs to small fabricators nearby,” Avila explained. “Our materials can all be sourced locally — it is mostly steel and a few imported parts like bearings and engines.”

Adriana Garties, chief technology officer, said the network of local fabricators means the Imara Tech production shop responds fast to demand changes. “There’s a huge amount of manufacturing capacity in Tanzania and most of it’s located in small, often informal businesses,” she said. “We train dozens of these technicians to make parts for our products. Local workshops fabricate parts to our high-quality standards and deliver them to our shop for assembly. Instead of a monolithic factory that’s slow to respond to seasonal fluctuations, we have a lean, flexible manufacturing network that creates machines on demand.”

D-Lab students helped build the Imara Tech team’s capability by running training sessions to enhance the skills of local engineers and technicians, empowering them to take ownership of production. This knowledge transfer was crucial for scaling the thresher technology.

Continuous improvement and development

Last year, a team with members from Imara Tech, D-Lab, and Twende, a local nonprofit that provides mechanical and electrical skills training to students, entrepreneurs, and business people, addressed a maintenance issue with the MCTs. Operators tended to run them 12 to 15 hours straight instead of letting the thresher rest every four hours. Plus, they often forgot to change the oil every 48 hours, causing overheated engine casings to separate, leaking oil.

(Photo: Imara Tech.)

The team developed for retrofit a low-tech electronic monitoring device directly wired to the motor. It monitors thresher usage and vibrations to predict potential engine issues. A red light glows when the engine needs oil, rest, or vibrates too much.

Imara Tech hasn’t stopped at threshers. It builds peanut shellers, mills, and oil presses, some of which run on renewable energy. It has developed a larger version of the MCT and a smaller version for shelling maize. It manufactures and sells chaff-cutting machines and plans to develop an affordable planting machine soon.

It also continuously upgrades manufacturing equipment. “Last year we operationalized a fiber laser cutting machine, and we are importing more equipment for sheet metal bending, rolling, and cutting angle iron and steel tubing,” Avila said. “So, we keep an eye on how the design can be improved as our production capabilities improve.”

“Sales increased steadily from 2019 when the company sold just 24 MCTs to 323 in 2024, a number that beat projections. Total sales to date are 1,156 units. Imara Tech surveys indicated that 55% of products were used for service businesses. Based on farms reached and household size, the company estimates that 118,272 people benefitted from mechanization.

Problems with more meaning

When he first arrived at MIT in Boston, Avila, who now lives in Tanzania, said he assumed he would work at a financial firm, NASA, or the Jet Propulsion Laboratory after graduating.

“I was interested in science for the sake of science,” he said after graduating in 2014. “Now it feels like the problems I work on have much more meaning, and it’s a constant motivator for me to take on new challenges. Now I’m much more interested in how science and technology play a role in people’s everyday lives.”

1. Bringing New Technology to the Last Mile Through Transformative Partnerships: Imara Tech and Farm to Market Alliance’s Farmer Service Centre Model, (Gigiri, Nairobi, Kenya, Farm to Market Alliance, 2022 case study), p.2.

2. Country Climate and Development Report, United Republic of Tanzania Agriculture Sector Background Note, (Washington, DC, World Bank Publications, 2024), p.8.

Designing the Future

An Introduction to Lean Product and Process Development.