While reading Jeff Liker’s recent Tesla article exploring contrasting viewpoints about the right level of automating work, I couldn’t help but reflect on a recent visit to Toyota Motor Kyushu, or TMK. Last month Mark Reich and I spent two days there walking the gemba. TMK is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Toyota Motor Corporation, based just outside Fukuoka City on the island of Kyushu. Toyota created TMK in the 1980’s to manufacture its then new Lexus brand. It continues to manufacture Lexus vehicles — one every 72 seconds during our time at the plant.

In his article, Liker reflects on the future relationship between man and machine, specifically on the question of whether the dream of full automation should indeed be an ideal future state. I got a sense of Toyota’s current thinking about this very question during my time there, and was intrigued by what I learned. Indeed, the TMK looks less like a factory from the future and more like a factory from the past. This is primarily due to something called “karakuri.”

Karakuri literally means a type of doll that moves with simple mechanics. In manufacturing, karakuri refers to simplified engineering for kaizen. Team leaders and operators are challenged to use levers, pulleys, counterweights, and gravity in order to increase productivity, quality, and safety. Utilization of compressed air, hydraulics, and robotics is prohibited. It’s as if TMK is trying to build the Lexus RX and CT on a shoestring budget. The roughly $186 billion (as of this writing) market cap company is bootstrapping its luxury vehicle assembly!

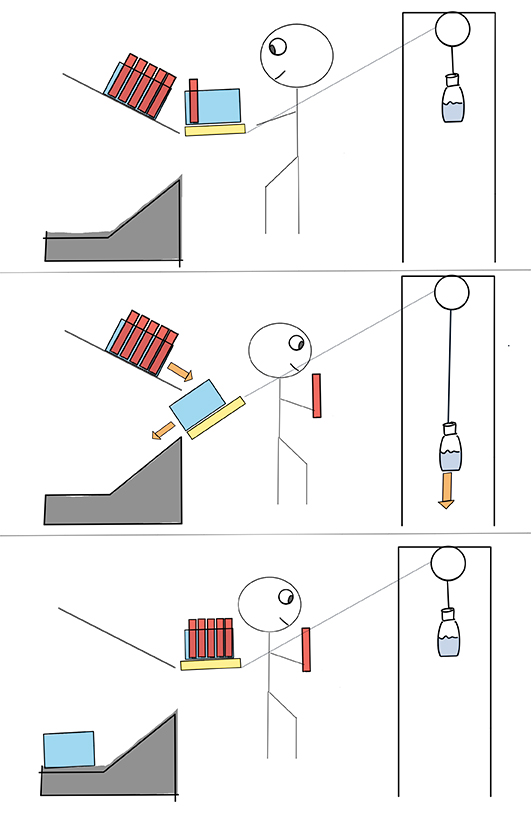

Karakuri is easily understood when observing it, but more difficult to understand through words alone. I have (poorly) illustrated one example that I witnessed in assembly. While I am not certain of the precise function of the apparatus, this illustration is based on what I gathered from observation. The parts container adjacent to the operator sits on a sort of trapdoor that is connected by a string to a partially-filled water bottle serving as a counterweight. Once the parts container empties, the counterweight falls, triggering the floor beneath the container to open. The container slides down a shoot for pickup by the material handler, while a full parts container slides into place for use. This karakuri removes the operator’s periodic work of taking down the empty parts container.

This is but one of dozens of examples that exist along the TMK assembly line. The proliferation of karakuri is driven by a two-year training program for team leaders. Coaches skilled in karakuri spend the first year training team leaders on karakuri engineering methods; they spend the second year teaching others how to lead operators practicing karakuri. The link between improving the work and developing people is explicit. Team leaders aren’t just challenged to improve the work through karakuri themselves; they’re challenged to coach their team members to do the same.

Karakuri demonstrates that Toyota’s working currency is brainpower, grown through rigorous problem-solving and mentors who challenge their students. The wallet takes a backseat to the brain. Toyota’s response to the challenge of increasing kaizen capability wasn’t to find smarter people or more clever machines. Instead, it was to 1) make kaizen more accessible by simplifying engineering and 2) develop people to make work better using the engineering.

It’s unknown what this specific factory tells about what all future factories will look like, but does provide an alternative scenario than the fully automated system some envision. Tesla is betting on a highly-automated factory in which some humans support a whole lot of robots: complex machinery supported by concentrated human capability. Toyota — at least for now — thinks it will have some robots supporting a lot of humans: simple machinery supporting distributed capability.

Thus far, Toyota is winning the argument. Clever use of pulleys, counterweights, and gravity by assembly workers is outperforming pricey robots trained by highly educated engineers.

This is not to say that Tesla can’t get to where it wants to go. It may very well build a lights-out factory churning out a million Model 3 vehicles a year (assuming customers want a million Model 3 vehicles per year). But its current state is what even its founder Elon Musk refers to as “production hell”, while TMK has been a J.D. Power Platinum plant for two years running.

What we can conclude for now is that TMK is producing the highest quality vehicles in the world by making ever-clever people and using ever simpler tools. For those anxious about the future relationship between humans and robots (who works for who or do humans work at all?) TMK offers reason to hope that humans will win the race — or at the very least have a long runway on which to run.

People are very good at making things, and at making things better. It seems that Toyota is betting that this won’t change anytime soon. For the time being, as a means of thriving in the future, they are investing in people and pulleys rather than robots.