Sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint the exact root cause of a problem, especially when one is masquerading as another. Our lean team at Indiana University Health Arnett Hospital recently had a memorable experience with that in our Invasive Outpatient Unit. We eventually realized it was a flow problem, but it took some trial and error to get there, including both A3 thinking and rapid improvement events. Here’s how it happened:

Problem and Root Cause

It all started when the Invasive Outpatient Unit experienced overscheduling of patients who needed to be prepped for and recover from procedures. When that happened our inpatient and outpatient procedures were completely overwhelmed. The working hypothesis was that our capacity was being limited by our own less-than-optimal use of prep and recovery rooms. We decided that additional space would need to be allocated to this unit to support the patient flow.

To solve the problem and decide how to best reallocate our available space, we conducted a Rapid Improvement Event (RIE) using A3 thinking principles. We gathered data on average prep, procedure and recovery time and determined the demand for each procedure. This allowed us to calculate the room capacity and number of staff required to support the demand.

It wasn’t what we were expecting.

The data revealed the reality, and we discovered that our theory of not having enough rooms was incorrect. According to the numbers, the current number of rooms we had available was more than enough to satisfy demand. We knew then we had to think beyond just problem solving. The true problem had to be somewhere else.

Experiments and Building Flow Cells

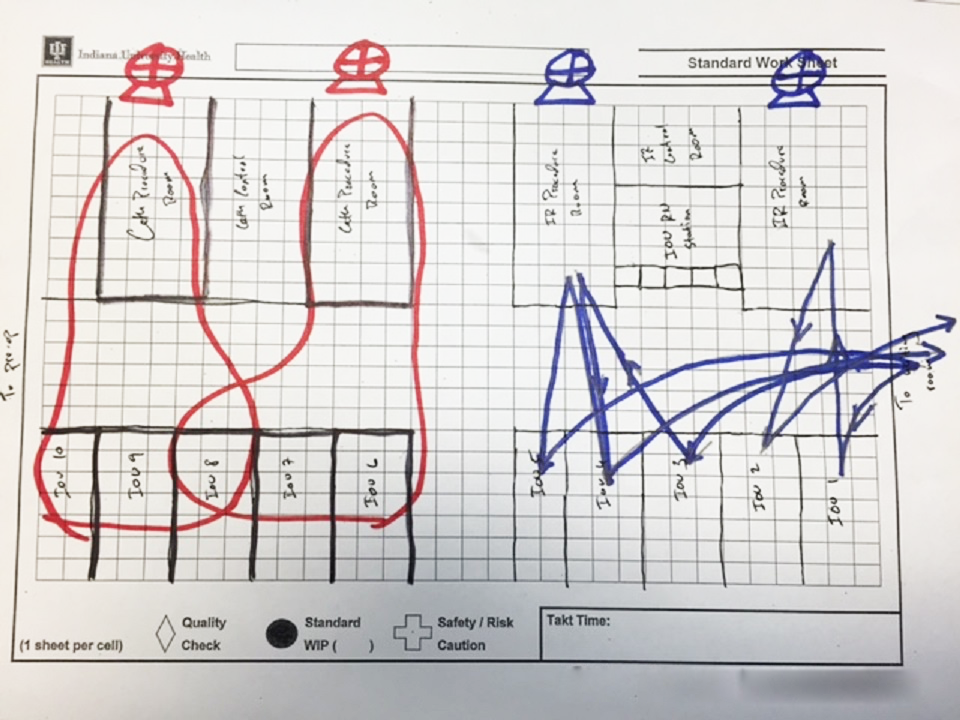

With our capacity hypothesis proven wrong, we realized that we must have a flow problem. We decided to try a series of experiments to put this to the test. We created flow cells in the area connecting the prep/recovery and procedure rooms. To help build the flow cell, we completed a “paper doll” exercise, using a sticky note to stand in as a patient going through a paper map of the prep, procedure and recovery in real time. We walked the walk of the “patient” to develop these specific flow cells.

Each flow cell comprised all flow cell components:

• We used “1:1 flow” to decrease staff travel and motion by putting patients in the rooms closest to their procedure, creating tight connections and natural work groups.

• We used “pull” techniques to determine the schedules in order to balance the work for good flow, or, in other words, only flow when downstream pulls. For example: we don’t start prepping a patient until we know a procedure room will be open by the time prep is complete.

• Using “6S” we stocked each room with the necessary supplies for the entire day, which enabled us to turn the rooms over quickly.

• “Standard work” was put in place to determine resources allocated to each flow cell based on demand and to increase the teamwork in the area.

• This standard work is deployed during daily morning huddles at the team’s “visual management” board.

Together, the flow cell created predictable patient flow to match capacity to demand, while eliminating overcapacity and increasing utilization.

Impact: Patient Care and Team Culture

Two months after the RIE, the unit’s utilization increased by more than 30 percent and we’ve increased the number of procedures supported by the unit from about 12 per day to almost 16 per day. Using lean methods, we provide care for more patients each day without limiting the roughly four hours spent with each patient. At the same time, we’ve significantly reduced patient wait time prior to the procedure. We are working to eliminate the process workarounds that resulted in lower patient satisfactions, delays in care and poor patient outcomes.

The unit’s effort through this RIE and associated sustainment activities is not only changing the way it does its work, but its culture as well. Members of the unit report that silos are breaking down between teams and the RIE created a new way to move forward, allowing teams to work together.