Terell Stafford is a world-famous jazz trumpeter and the Director of the Jazz and Instrumental Studies Program at Temple University. Stafford always wanted to be a trumpet player and was obsessed with classical music as a child, but eventually chose to devote his talents to jazz.

At the Lean Healthcare Transformation Summit in June, Stafford told us why he practices three routines daily, without fail, to ensure his success as a musician.

Stafford said that the following routines are essential because they ensure that he maintains fundamentals and provide him with structure for continuous improvement and innovation.

- Maintenance routines – Stafford described his maintenance routines as exercises that he performs to maintain fundamental skills and his fitness as a musician, such as lip positioning, finger work, and breathing. He’s been practicing the same exact routine for over 30 years, every day. He will wake up hours early or forego other activities rather skip his maintenance routine.

Stafford insists that his students develop their own maintenance routines. Their routines do not have to be the same as Stafford’s, but the routine has to be one that the student will commit to practice daily for the rest of their musical career.

- Growth routines – Stafford uses his growth routines to practice anything that he does not perform to standard during the maintenance routines. Stafford told the Summit audience that: “every day I have failure – that’s why I have my routines of practice. If I fail at things, I know I have an opportunity to grow and learn.” If a certain note he played wasn’t consistently on key, or a fingering pattern wasn’t precise, he uses his growth routines to challenge himself to improve and get back to his standard.

- Exploration routines – Stafford described his exploration routines not as specific patterns of practice, but rather as dedicated time he sets aside for learning something new. This time is for innovating, growing, and developing new ideas, as he said, “to take what I do to the next level.”

His practice during his exploration time can take a variety of formats, such as listening to another artist’s music or trying to write his own composition. Stafford said that he always wants to spend more of his time in exploration, but that he makes himself go through the rigor of his maintenance and growth routines before he allows himself time for exploration and innovation.

Stafford’s routines are not endpoints unto themselves, but rather are structures that he uses to create the condition for learning and continuously improving as a musician.

Routines of practice for problem solving thinking

The lean practitioner in me couldn’t help but draw the parallel between the purpose of Stafford’s three routines with the different types of problems that can be addressed using the framework of A3 problem solving thinking.

- Establish and follow a standard – before we can improve, we have to first establish a standard and then work to maintain a standard, every day. This reflects Stafford’s maintenance routines.

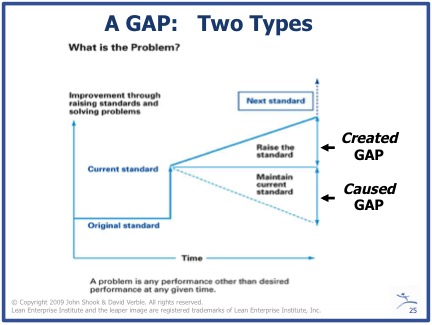

- Close a caused gap in performance (caused gap) – if there is a gap between the current standard and what is actually happening, we need to work to close the gap through determining the root cause(s) and then putting in place countermeasures to close the gap. This reflects how Stafford approaches his growth routines.

- Establish a new target and innovate to a new standard (created gap) – if we want to reach a higher level of performance, we establish a new target and then work to close this created gap in performance through experimentation and innovation. This sounds like Stafford’s exploration routines.

Lean frameworks as practice routines for learning and improvement

Stafford’s comments about his structured routines for daily practice led me to reflect the importance of routines and frameworks to create the conditions for continuous improvement for us lean leaders.

There are many structures and concepts things that we consider tools that are simply frameworks that allow us to practice routines of deeper thinking. For example, the problem solving A3 process described by John Shook in “Managing to Learn” and the coaching “starter kata” described by Mike Rother, are both structured routines to develop more effective problem solving habits. Like Stafford’s routines, these frameworks are not endpoints unto themselves, but rather are structures that support the conditions for deeper learning.

You will often hear lean coaches, including myself, emphasize that A3 thinking is NOT about a template, but about the thinking process that the A3 framework guides the problem solver through and the pattern of “catchball” between a problem owner and a coach. As Mr. Isao Yoshino, John Shook’s first manager at Toyota and one of the models for Sanderson in the book “Managing to Learn” told me recently, “The A3 isn’t a magical tool.”

The framework the A3 template represents is a specific structure that can help create the habit of deeper problem solving process even in absence of the actual A3 paper. The magic is in practicing the routine of structured thinking, not the tool itself.

Lean frameworks as practice routines for personal learning and improvement

One Lean framework that I have found useful for identifying routines to practice for improvement is using A3 thinking focused inward on one’s own opportunities for improvement.

In a past Lean Post article, I shared how using the Personal Improvement A3 process has been a useful framework for identifying routines to practice for personal improvement. Not only have I become a better question asker and listener, I have identified specific routines that support ongoing improvement, such as setting daily intention for practice and reflection. This feedback loop routine helps me know if I’m maintaining or improving on my coaching skills.

The habit of using the structure of A3 thinking to improve oneself also leads to the practice of other important habits such as reflection, asking questions, and problem solving. It becomes a keystone habit, which Charles Duhigg defines as habits that “help other good habits take hold.”

Develop your own routines of practice to maintain, grow and innovate

Mr. Yoshino and I also have discovered that we both use A3 thinking for personal practice. The Personal Improvement A3 approach that I shared above focuses on specific behaviors for improvement, while Mr. Yoshino shared with me that he uses “personal hoshin kanri” to set annual personal goals.

Mr. Yoshino encourages his university students (he now teaches at a university in Nagoya) to develop their goals using the hoshin A3 format as a way to learn and practice the thinking routine of goal setting.

When we spent time together earlier this year, he shared his personal hoshin and encouraged me too to develop my own plan. He gave me an example A3 template, but said that my hoshin A3 doesn’t have to look just like the “Yoshino format.” He encouraged me to develop my own “Katie way.” What he meant by this was that my hoshin A3 didn’t need to look exactly like his, such as symbols, tables, and exact format, but rather that I should follow the principles and then create a structure and visual representation of my thinking that works for me. This harkens back to Stafford’s instructions to his students to create their own maintenance routines.

What is your routine and structure for daily practice and improvement?

We all have to practice daily, without fail, to maintain our skills and desired habits, work to close our personal behavioral gaps, and then have space for innovation and developing new skills and habits. What will be your routines for maintenance, growth, and exploration? What specific patterns will you practice daily, with intention? How can you use the structures and frameworks within lean practice to support your daily routines for practice?