Dear Gemba Coach,

My understanding is that implementing lean means setting up a lean management system. You seem to disagree. Would you explain?

I don’t disagree as such, implementing a lean management system is indeed part of the effort, and will bring in low-hanging fruit – but I strongly believe that it’s not what makes lean a superior management approach, or indeed, what makes it so interesting.

To start with, what would be the bare bones of a lean management system? Most companies adopting lean, tend to focus on:

- A kaizen workshop improvement program (often using VSM to fix problems and generate “savings”).

- A shop-floor visual management system – hopefully a pull system with kanban (if not, what’s lean about it).

- A team ritual practice, such as stand-up meetings, problem-solving time-outs, team huddles, and so on.

- A policy deployment steering process, involving gemba walks from management, setting and tracking objectives, and some sort of maturity audits based on roadmaps or “leader standard work” and the like.

Stuff that is considered more “advanced” and that varies from company to company, such as a suggestion system, TPM program, A3-based universities, jishuken activities, dojos, very rarely jidoka practices, and so on.

Now, as you can guess, this whole thing takes a while to implement wall-to-wall, requires a measure of lean bureaucracy (the lean promotion office, lean “standards,” deployment plans, training sessions, model lines, etc.), and keeps the company fairly busy for the next couple of years.

It’s also magic.

Companies that are serious about implementing such a lean management system will immediately see two benefits:

- Performance improves because the simple fact of motivating people in setting up the system makes them look at how they work differently and, as they get pushed by consultants to do something different, they often solve obvious problems and gather low-hanging results.

- It clarifies work considerably – if the lean management system is maintained with enough disciplines, the workplace becomes a far more legible place, which makes management’s work eassier (from senior leaders to middle-managers).

But then it stalls.

First, improvements slow down to the point that the financial benefits of maintaining the system (the lean promotion office, the workshop time commitment, the consultants, etc.) has to be argued against bottom-line benefits. Secondly, people find the bureaucracy of lean increasingly tiresome: having to show up at stand-up meetings where nothing ever changes, maintaining all these visual boards no one ever looks at, finding time for kaizen workshops without clear benefits, preparing gemba walks to make senior leaders feel good and hide the real problems, and so forth.

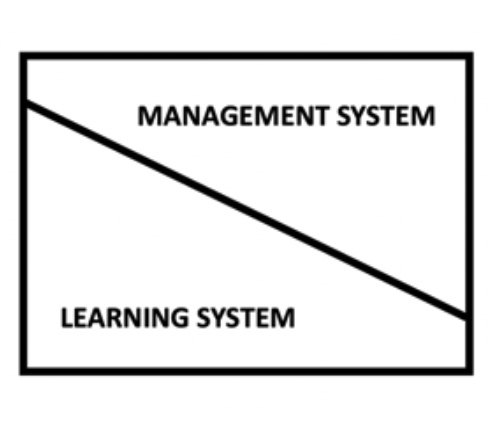

The point is that this “lean management system” is only a step – not an end in itself. Too much focus on the management system is like confusing the scaffolding for the sky-scrapper we’re trying to build. Yes, the scaffolding is necessary – but it’s just the scaffolding.

Three Tough Questions

The great lean leaders I’ve been privileged to meet tend to think very differently. They’ve identified clear technical challenges they need to solve in order to help their customers better, offer more value than their competitors, and get every one’s minds working on these key issues. The management system is a tool that helps those kinds of leaders feel their way around three very deep and very difficult questions:

- Are we solving the right problems? Or are we missing what’s at play (think of the recent U.S. election and the near-consensus of the media on who had the highest chance of winning).

- Are we doing so smartly? Or are we unwittingly creating more wasteful solutions?

- Are we learning from all the creative ideas people have at the front-line? Are we supporting those with breakthrough thinking, or ignoring them?

To answer these deep questions, one needs to use the lean system as a learning system, not just a management system.

Let’s go to a gemba and take a concrete example. The French Lean Institute, Institut Lean France, is a voluntary association where each institute member donates some of their time to help promote the lean message in France. We do so mostly in the form of conferences (several speakers over one or two days), masterclasses (one speaker over one day), publications (blog posts and books) and “academies” (a community of practice where members do gemba walks in each other’s companies on themes such as lean engineering, lean office, etc.). We do charge for these events to fund the organization, but members work pro bono.

As you can imagine, busy people are willing to help but, well, are busy and have other priorities and coordinating all of this was a real mess. Until one of our sensei, Catherine Chabiron, decided to apply the lean tools to our own activity. She set up a one-page indicator sheet to track our progress monthly. She set up a regular conference call that works as a stand-up meeting for our core members. She drew up a heijunka board to visually control the rhythm of events. She now acts as the “small train” by pulling the work just-in-time. For instance, when it’s time to come up with a new editorial blog post, I don’t have to worry about it, because I know Catherine will ask me a week before, so I can deliver on time.

This has transformed our efficiency. We run more events than ever, our community is growing. We’re producing new material – one of our sensei, Cécile Roche, has published her second book and is working on her third, Godefroy Beauvallet and myself have produced a book in French to demystify “lean management” for French managers. Our members are happy to contribute. We have discovered many problems and are establishing standards about doing this or that. Lean, right?

Hmm …

Are we improving? Are we learning? Hard to say.

And Two Fundamental Ones

To start with, when we try to discuss what improving would mean for us, we soon realize that not only are we not sure what that means individually, but also we don’t see things the same way. Oh, it’s easy to agree that we need to improve logistics for our audience: smoother-run events, easier to handle website, that sort of thing. But what about value?

At its core, the lean management system is there to help you answer two fundamental questions:

- Value analysis: What can I improve for customers and employees in the contracts I’m currently delivering?

- Value engineering: so that I know what to focus on for my next offer, whether product or service, to my present and future customers?

Value analysis/value engineering is the true two-step engine that drives real lean improvement – the rest is the plumbing that makes that work. Without plumbing, the engine doesn’t run, but without running the engine, the machinery rusts and drifts away.

If we go back to our case, this is far from simple. Take our “masterclasses” for instance – each Institute member donates one day a year for a talk on their lean expertise. What should we improve? More attendees? That would be nice, since it would generate revenue for the institute as well as attract more people. But is that our core mission? Isn’t it that for the more advanced messages or experiments, we’re unlikely to find a mass audience but we still need to hold the masterclass even if only 3 people show up? Are masterclasses devices to cash in on lean by watering down the message for a larger audience or, on the contrary, opportunities to push the frontiers of lean or keep obscure technical details alive?

I have no clear answer to any of these questions, but I do know that we need to ask them in order to learn and grow, AND the lean management system Catherine has put in place, great as it is, won’t ask them by itself. Left to its own devices, it will constantly focus us on logistics (very important) but not necessarily quality or, deeper, value.

Jidoka Goes AWOL

Focusing on value means using the management system in a very different way by questioning it constantly: what is the system telling us today about value? What is easy to do? What is hard? What do we think we should do, but encounter resistance? How do we know we’re progressing or being taken away by the current?

When Catherine and I ask these questions by looking at the management system, more detailed, specific things appear. For instance, why so little mention of jidoka? Toyota experts will all agree that jidoka is the hidden part of the iceberg, and largely as important as flow, if not more. And yet, whether at our Institute or within the whole Lean Global Network it barely gets mentioned. Tom Ehrenfeld recently did a roundup of material on jidoka for lean.org and reached the same conclusion: JIT is vastly over-represented in the literature. How do we face this challenge? What do we do?

This is not to say we don’t learn. For instance, we see at conferences that line executive speakers describing their lean efforts have a much greater impact and “wow” effect than staff speakers in a lean or improvement role (who are seen to be selling their wares). Of course, it’s much easier to find a staff speaker than an executive one, so this frames a very interesting challenge for us: how do we reach a 50/50 target of line speakers?

But is that important learning? How would we know? The management system is a powerful tool to help us distinguish what are our key challenges, but it can also be misleading if narrowly treated as … a management system. For instance, years ago John Shook defined the key challenges of lean thinking: fundamentals (such as the jidoka question) and frontiers (applying lean in new fields). Our management system, by itself, will not help us on these fronts unless we orient it towards these questions.

Yes, the management system is important – but it’s only the starting point, the entry fee. The real value from lean comes from what the management system teaches us about value – if we’re ready to learn. Because learning is always hard, this means looking at the lean system as a learning system first:

- How can we better improve customer value?

- How can we reduce lead-times everywhere?

- How can we stop closer to where defects are made?

- How can we engage and involve employees further?

- How can grow greater mutual trust between management and employees?

These are the core question the lean system asks – should we listen …